How to Recover From Burnout With 14 Exercises & Treatments

Does your client complain about feeling emotionally exhausted, uninvested in their work, and questioning their career decisions and abilities?

Does your client complain about feeling emotionally exhausted, uninvested in their work, and questioning their career decisions and abilities?

If so, they might be experiencing burnout – the final stage of poorly managed workplace stress.

The best way to explain the effects of work and leisure activities on our health is to use the metaphor of a battery. Work activities delete our battery charge, but certain activities can recharge us. If we don’t recharge, our battery is going to run empty. If that happens, we have developed burnout.

In 2020, Gallup reported that three-quarters of employees experienced burnout ‘always,’ ‘often,’ or ‘sometimes.’ Burnout has detrimental consequences to workplace productivity and employee health; it must be addressed.

In this post, we’ll explore various strategies that can be used to recover from burnout.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises (PDF) for free. These science-based exercises will equip you and those you work with, with tools to manage stress better and find a healthier balance in your life.

This Article Contains:

- How to Recover From Burnout

- 3 Scientifically Proven Treatments

- Burnout Management: The Importance of Self-Care

- Recovering From Burnout: 4 Helpful Exercises

- How Long Does It Take to Recover?

- A Look at the 6 Recovery Stages

- Best PositivePsychology.com Burnout Prevention Tools

- A Take-Home Message

- References

How to Recover From Burnout

Burnout is largely a result of poorly managed workplace stress, and the primary responsibility for preventing it rests with managers (Gallup, 2020).

Besides talking to managers or supervisors, there is little that employees can do to change the company culture or workplace demands. Unlike employees, managers have the power and resources to change the workplace environment. With positive leadership, good managers will know the warning signs of burnout and should be able to intercede.

Fortunately, there are several things your client can do at home to recover from burnout, without help from a manager.

The effort–recovery theory posited by Meijman and Mulder (1998) explains how burnout can be accelerated by daily activities.

In a nutshell, they argue that:

- Work-related activities require cognitive and physical energy to complete; in other words, there is a cost involved.

- This cost can be recovered after a brief break from work.

- However, if the break is too short or if the break is never taken, then the cost is never recovered.

- When an employee with an energy deficit approaches work-related tasks, their productivity will be reduced and they work slower. To make up for the shortfall, the employee might work overtime, which again prevents recuperation from the cost of work-related activities. As a result, the employee is continuously working at an energy loss and can never fully recuperate.

With this in mind, employees recover from burnout when their cognitive and physical resources are recharged. To recharge these resources, employees must take a break from work and participate in other activities with the following properties:

- They have beneficial consequences.

- They promote good health and habits.

- They foster supportive relationships.

Activities that can support burnout work recovery include:

- Downtime activities:

These are activities that are not outcome driven or productive, require little effort, and are purely enjoyable. Examples are coloring, watching tv, and napping. - Social activities:

These include social interactions with friends and family. The goal of these social interactions is to develop healthy support networks to protect clients from stress. - Physical activities:

Regularly taking part in sports can reduce the harmful effects of stress. Exercising in a group or with friends can also foster social relationships and encourage a healthy sleeping pattern.

3 Scientifically Proven Treatments

Each treatment is briefly described below.

Daily recovery is vital

Overwhelmingly, research suggests that daily recovery efforts are more important than waiting for the weekend or a vacation (Derks & Bakker, 2014; Oerlemans & Bakker, 2014).

In other words:

- More frequent breaks are better than one long annual vacation.

- Daily recovery periods are more important and effective than weekly, or less frequent, recovery periods.

Put your smartphone away

By reading participants’ regular journal entries, researchers gained insight into natural strategies that participants used to combat burnout.

Derks and Bakker (2014) found that burnout recovery was hampered by work–home interference, which is when our home and work needs conflict. The researchers argued that smartphone use after hours put people at risk of work–home interference, specifically:

- Receiving text messages about work after work hours

- Actively checking work email after work hours

Derks and Bakker (2014) divided their research participants into two groups: those who used their work smartphone after hours and those who did not. Participants who used their work phone after hours were more likely to experience work–home interference and struggle with burnout recovery.

If these participants could ‘disengage’ from their work and not use their work phones, then they were able to relax.

If you were wondering, avoid syncing your smartwatch with your work email; it will have the same deleterious effects.

Yes, you should lie on the couch

In another diary study, Oerlemans and Bakker (2014) were interested in how burnout recovery was affected by the following three daily activities:

- Social activities – spending time with friends and family at home or outside of the home; taking part in social activities with other people outside of the home

- Low-cost activities – lying on the couch, watching tv, doing nothing, napping

- Physical activities – participating in sports, yoga, or exercise

Oerlemans and Bakker (2014) analyzed the diary entries of 247 people across two weeks. To measure burnout recovery, they asked participants to rate statements relating to:

- Physical vigor, characterized by feeling energetic and strong

- Cognitive liveliness, characterized by thinking quickly, feeling creative, and coming up with novel solutions and ideas

- Recovery, characterized as feeling rested and having sufficient time to recover

Overall, burnout recovery improved following participation in any of the three types of activities.

However, when Oerlemans and Bakker (2014) split the participants into groups of high-risk versus low-risk for burnout, they found the following for the high-risk participants:

- Low-cost activities improved physical vigor and cognitive liveliness, but not feelings of recovery.

- Social activities improved physical vigor, cognitive liveliness, and recovery.

- Physical activities showed no improvement for any of the three outcome variables.

Other strategies

Other recommended strategies known to assist with burnout recovery include the following (Demerouti, 2015; Derks & Bakker, 2014):

- Detach from work. Remove yourself mentally and physically from work after work has ended. At the end of the day, close your laptop and walk away.

- Deploy coping strategies that directly target a stressful situation, rather than coping strategies that aim to change feelings about a situation. These are known as problem-based coping strategies and emotion-based coping strategies, respectively. Avoidance strategies such as ignoring the situation are extremely unhelpful.

- Employees who used compensation strategies to cope with negative job reviews were better able to cope with workplace stress. Compensation strategies include relying on other people for help (e.g., forming a daily writing group), using technology (e.g., adding reminders to their calendars), and learning new skills.

- Promote good healthy habits, such as a healthy diet, regular exercise, and enough sleep.

Other recommended strategies include relying on religious or spiritual guidance, including:

- Meditation

- Prayer

- Attending religious ceremonies and support groups

Burn out to brilliance. Recovery from chronic fatigue – Linda Jones

Burnout Management: The Importance of Self-Care

Unfortunately, your client might not have the necessary power or resources to make the changes needed in the workplace to counteract burnout. However, they can promote self-care and put themselves first.

The best way to counteract the cost of work is self-care.

Specifically, your client should focus on their wellbeing first. The importance of self-care is simple when we return to the battery metaphor. If your client’s battery is not fully charged, then they cannot provide enough energy to their work and life responsibilities.

By improving their wellbeing, clients will become more resilient to workplace stress.

Promoting self-care can be difficult especially when coupled with bad habits, such as working overtime, responding to work messages or texts after hours, and saying yes to everything, resulting in an unreasonable workload.

To aid your client, encourage them to place importance on the following:

- Downtime tasks include activities that require little effort to complete, have no productive outcome, and are not deadline driven. Examples include reading, watching tv, coloring, and napping. These tasks should have little to no physical or cognitive demands.

- Social tasks, such as spending time with family and friends, will foster a supportive social network for your client. By contacting friends and family, clients will have an outlet to talk about work stressors.

- Physical activities, such as exercise and yoga, will help your client feel less stressed and also help encourage a better sleep cycle.

- General health refers to satisfying other important drives such as eating and sex. Eating a healthy diet, rather than eating irregularly or unhealthily, will contribute to an overall feeling of wellbeing. Enjoying sexual activities with one’s partner will help foster feelings of love, intimacy, and support. Other activities that can help promote general health include meditation and enough sleep.

Furthermore, your client should learn how to identify signs that they are tired or stressed. For example, do they report not enjoying their hobbies or feeling more irritable, demotivated, or tired? These could be signs that your client must take extra measures to recharge their battery.

Everyone has a fixed amount of energy per day that is divided between work, family, rest, and leisure.

If too much time is spent on work and too little energy on rest, family, and leisure, our wellbeing will suffer in the long term, which could lead to burnout. To maintain both happiness and productivity, a healthy work-life balance is required.

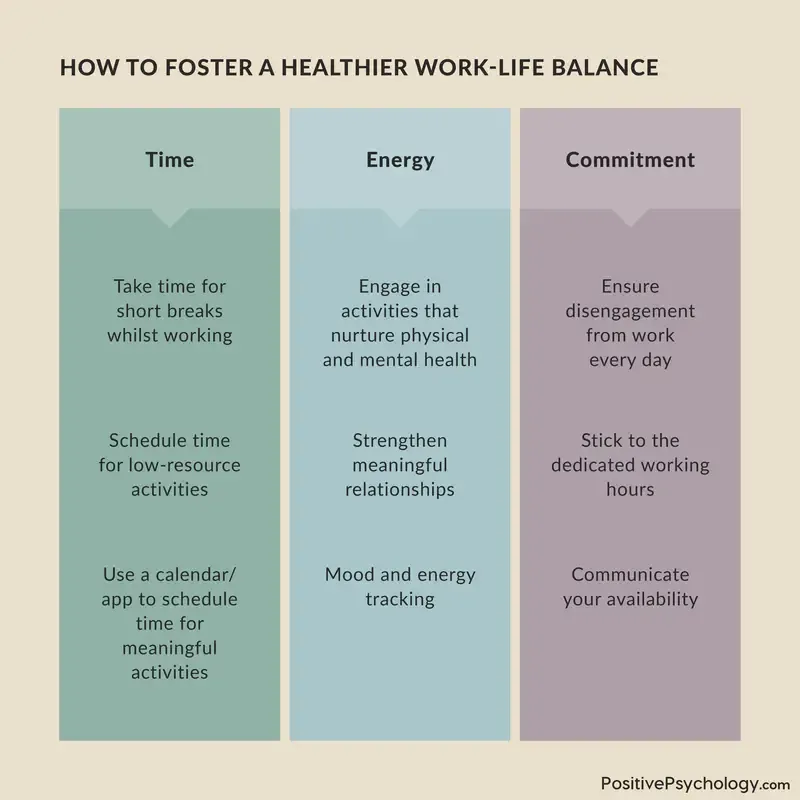

According to Kalliath & Brough (2008), a healthy work-life balance is secured when individuals have enough time, energy, and commitment to engage in home-life or family-life activities:

Time

Take short breaks while working with breathing exercises or a mindful snack. Schedule enough time for low-resource activities, such as power naps or meditations. In addition, use a life calendar or app to schedule time for joy- and meaningful activities.

Moreover, frequently engaging in physical or social activities fosters happiness and ensures a healthy work-life balance (Kelly et al., 2020).

Energy

Putting energy into exercising, hobbies, or a healthy sleeping routine is essential for your physical and mental health. By reflecting on activities, habits or thoughts, and feelings, you can find out what helps you personally and which activities to prioritize.

Furthermore, taking the time to strengthen meaningful relationships with friends or family is one of the greatest predictors and facilitators of subjective wellbeing (Froh et al., 2007).

Commitment

Ensure to disengage from work by logging off work systems, avoiding linking your work email to your private phone, and checking work-related messages.

It’s also important not to work after hours, to communicate your availability, and to learn to say “no.” For example, mention in your email signature that an answer can be expected during normal working hours (Nortje, 2021).

Recovering From Burnout: 4 Helpful Exercises

However, to help you and your client, we recommend the following exercises.

At PositivePsychology.com, you’ll find several breathing and self-awareness exercises that can help with stress. These exercises can easily be used in sessions with your client who can then use them at home.

Deep breathing can assist with feelings of stress and anxiety and may help with burnout recovery.

As a start, look at these exercises:

To help clients cultivate better awareness of their stress responses, this Reactions to Stress exercise can help. In this exercise, your client will develop a table to record capture stressful events and their reactions to them. This is especially important in situations where repeating patterns have become entrenched.

Our internal and external resources can provide a potentially endless amount of support that sustains us during stressful times and when facing challenges. The Identifying Your Stress Resources exercise contains valuable questions to help clients recognize their resources and identify how they can support their strengths.

How Long Does It Take to Recover?

It’s difficult to estimate the time needed to recover from burnout.

In a study aimed at improving burnout recovery, the intervention results showed positive effects (Hahn, Binnewies, Sonnentag, & Mojza, 2011). Participants in the treatment group received training about the importance of self-care, recovery from burnout, goal setting, time management, how to disengage psychologically from work, and other strategies (the full program is described in Hahn et al., 2011).

Compared to baseline measurements taken before training, participants who received training showed the following:

- One week after the second training session, recovery scores were higher, quality of sleep was better, and self-efficacy scores were higher.

- Three weeks after the second training session, recovery scores had plateaued, quality of sleep improved further, self-efficacy improved further, negative affect was lower, and perceived stress was lower.

The difficulty with an intervention study is that recovery was aided through an artificial environment (i.e., the study design itself).

Naturalistic studies show more variability in burnout recovery because employees are not actively treating their burnout through some type of intervention. In some instances, employees still report feeling burnout even after one year, and sometimes even after a decade (Cherniss, 1990).

Other naturalistic studies suggest recovery takes between one and three years (Bernier, 1998). Some researchers question whether recovery from burnout is even possible (Hakanen & Bakker, 2017).

Despite this, the published evidence suggests that regular participation in social, physical, and low-cost activities will benefit burnout recovery (Derks & Bakker, 2014; Oerlemans & Bakker, 2014).

Your client must actively monitor their feelings and thoughts, looking for signs of stress or exhaustion, which might suggest that they’re at risk of burnout. As a practitioner, you can also apply these burnout tests to monitor your client.

A Look at the 6 Recovery Stages

Stage 1: Admitting there is a problem

At this point, employees realized that something was wrong. They felt tired and overwhelmed and displayed psychological and physical signs of burnout. These symptoms continued to escalate, and with feedback from family and friends, employees came to realize that they were experiencing burnout.

Stage 2: Distancing from work

After recognizing that work was problematic, employees took a break from work. This break was psychological and physical. For most employees, this break was framed as sick leave, but sometimes even resignation.

Bernier (1998) reports that some participants took an average of 3.5 months of sick leave, but in some instances, they took up to 11.5 months. During this stage, employees had to learn to distance themselves from work psychologically (e.g., not thinking about work or feeling time pressures).

Stage 3: Restoring health

During the third stage, employees reported they slept excessively; they either slept for longer periods in a single sitting or took frequent naps.

Besides sleep, employees also engaged in other low-cost activities and reported not wanting to complete tasks that were too draining.

After feeding these physical needs, employees did things purely for the ‘fun’ of it. They started to reengage with their hobbies and enjoy physical activities.

Stage 4: Questioning values

By now, employees could reflect on their old values and took efforts to replace these with new efforts. They questioned what they thought was important and why, and then found meaning in new values.

One common change during this stage was that all employees placed more emphasis on their health.

Stage 5: Exploring work possibilities

During the fifth stage, employees worked hard to find job opportunities that aligned with their new values.

The time taken to find a satisfactory work environment differed between employees, and employees explored many opportunities.

Stage 6: Making a break, making a change

Finally, employees had to take a break from their work and their previous work stressors before finally achieving workplace stability.

In some instances, employees tried to return to the original workplace, but when they did, they realized they had to break away completely.

Best PositivePsychology.com Burnout Prevention Tools

In this article, we’ve looked at some useful exercises that can be adapted for clients who are experiencing burnout. These free tools can be found in our 3 Stress and Burnout Prevention Exercises Pack (PDF).

First, we recommend Strengthening The Work-Private Life Barrier, which will give both you and your client insight into the behaviors, beliefs, and conditions that create metaphorical “holes” in the barrier between work and private life. In doing so, clients are better equipped to create a strong barrier between the two to help them restore a healthy balance.

Second, the Energy Management Audit is a very useful tool for your client to use when assessing their energy levels in the following four life domains:

- Physical

- Mental

- Emotional

- Spiritual

By assessing their energy levels, your client can learn to recognize signs of exhaustion before they reach burnout. Additionally, this tool will highlight the areas of their lives your clients are neglecting and remind them to balance their energy across all domains.

If you want to assess your client’s positive outcomes following a stressful event, then we recommend The Stress-Related Growth Scale. This 50-item assessment instrument is a useful tool for measuring stress-related growth, which allows clients to consider the positive benefits of challenging experiences for their relationships, thinking, and coping.

You can access all these exercises by downloading our 3 Stress and Burnout Prevention Exercises Pack (PDF).

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others manage stress without spending hours on research and session prep, this exercise pack contains 17 validated stress management tools for practitioners. Use them to help others identify signs of burnout and create more balance in their lives.

A Take-Home Message

Our batteries can only last for so long before they need recharging.

It’s impossible to avoid stress at work completely, and sometimes clients will need to put in extra hours to complete a task. This is normal. However, in anticipation of these normal occasional work pressures, it’s even more vital that your client’s battery is fully recharged.

Although treating burnout is important, it’s even more important to prevent it.

Regular recharge moments alone or with friends and family lay down the foundation for a stronger battery in the future. Your client should not wait until they feel burnout symptoms to start focusing on the benefits of self-care and stress management.

Burnout is not limited to only your clients; as a therapist, you are also at risk. So make sure to look after yourself too, and use the advice in our related self-care for therapists article to help you mitigate your workplace stress, as well as our related post – understanding therapist burnout.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises (PDF) for free.

- Bernier, D. (1998). A study of coping: Successful recovery from severe burnout and other reactions to severe work-related stress. Work & Stress, 12(1), 50–65.

- Cherniss, C. (1990). Natural recovery from burnout: Results from a 10-year follow-up study. Journal of Health and Human Resources Administration, 13(2), 132–154.

- Demerouti, E. (2015). Strategies used by individuals to prevent burnout. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 45(10), 1106–1112.

- Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Smartphone use, work–home interference, and burnout: A diary study on the role of recovery. Applied Psychology, 63(3), 411–440.

- Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., & Emmons, R. A. (2007). Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 45(3), 213-233.

- Gallup. (2020). Gallup’s perspective on employee burnout: Causes and cures. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/282659/employee-burnout-perspective-paper.aspx

- Hahn, V. C., Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Mojza, E. J. (2011). Learning how to recover from job stress: Effects of a recovery training program on recovery, recovery-related self-efficacy, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 202–216.

- Hakanen, J. J., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). Born and bred to burn out: A life-course view and reflections on job burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 354–364.

- Kalliath, T., & Brough, P. (2008). Work-life balance: A review of the meaning of the balance construct. Journal of Management & Organization, 14(3), 323-327.

- Kelly, R. K., Jones, J. L., McFarlane, A. C., & Murray, S. M. (2020). The impact of perceived social support on mental health in military personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(3), 329-342.

- Nortje, N. (2021). Burnout prevention: A practical guide for healthcare professionals. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(1), 84-89.

- Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. J. de Wolff (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 5–33). Psychology Press.

- Oerlemans, W. G., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Burnout and daily recovery: A day reconstruction study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(3), 303–314.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (54)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (45)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (14)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (42)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (13)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)

What our readers think

Great article!

Thanks so much.

I am still recovering from work place stress from 2016. I was able to work 50 hours a week easily but 6 years on I am only able to work 15 hours a week.

Which is slowly increasing but how come the recovery time is so slow? And how can I speed it up? I am doing a lot of the things you mentioned already.

Hi James,

I’m sorry to read you’re experiencing burnout. It’s only natural you’d be eager to return to your previous style of working — this must be very frustrating. Assuming you’re working with a medical professional as you continue recovering, I’d encourage you to continue updating them about your experience (and if you’re not working with a professional, I’d recommend speaking to your doctor to get put in touch with some support).

I’d offer two thoughts. My first thought is around work design and person-job fit. If you love what you do and most of the activities involved in the job feel energizing for you, that’s fantastic and there’s no problem. However, sometimes burnout results when the job we’re doing (or the way the work is designed) does not fit us. In these instances, we may find an inability to re-acclimatize to the work after a period of burnout, as it turns out the work never really suited us in the first place. You might find this blog post (and the others linked throughout it) useful for exploring this theme.

My second thought would be to check in with your expectations for yourself. The feeling that we can’t do the things we used to do can be psychologically painful. We feel as though we should be able to do the things we used to and may beat ourselves up when we can’t, when really these may be impossible standards. The remedy involves accepting yourself and the things that are not necessarily within your control. It’s a paradox in some ways, but if you can practice acceptance of your present situation (and of yourself) you may find your energy lifting faster. If you search our blog for ‘radical acceptance‘ and ‘self-acceptance‘, you’ll find several posts on these themes that include useful activities and exercises.

I hope this helps, and I sincerely wish you all the best with your recovery.

– Nicole | Community Manager

I really enjoyed this article. Thank you for approaching burnout and the changes you need to make to your life.

I too had to resign from work in 2020. Unsympathetic bosses and bullying pushed me into severe anxiety, major depression when menopause arose. I’d start to recover, think about a new job in my old field and get worse again.

Working with a psychologist I realised that I had fallen so far from my beliefs in what I did, was suffering trauma from the stress endured I changed direction. In fact, the effects on my brain and the yoga teacher training I did during this time fascinated me..and I found a Coursera course on Intro to Psychology when I started with a psychologist (not knowing much of this field at all.) I am now studying for a graduate diploma in science in psychology.

I am learning to manage my energy, and as it is totally under my control can just give up on any day and take a rest. I have found I need to do any reading in the morning, but can listen to lectures and type notes un the afternoon.

It is still difficult, and I couldn’t work 40 hours per week…where before, like James, 50-60 hours were east. But it is getting better, slowly, and I am so thankful for the support I had from GP, counsellors and psychologist.

Hi Sine,

Thank you so much for sharing your story. It sounds like you’ve really come a long way — good for you!

Although going through traumatic experiences like burnout can be very difficult, they can also present important opportunities to reconnect with your values what’s important to you in life, which sounds like it’s been the case for you. And indeed, one of the kindest thing you can do for yourself moving forward will be to keep checking in with your own energy levels and allowing yourself to rest when your body is telling you to.

I hope you continue to enjoy your exploration of psychology. I think it’s the most interesting field out there, but I’m biased of course 😉

– Nicole | Community Manager

Hi, I work in K-12 special education. The COVID-19 pandemic has created an incredibly high stress environment dealing with so many needs. Many of my coworkers are burnt out and I have realized that I too am experiencing burnout. We can’t really change workload demands and can’t leave education(yet). Do you have any more articles that focus on self care and recovery? And for people with limited time?

Anything is much appreciated!

Hi Muna,

Sounds like a very challenging time for you and your colleagues. I hope the pressure can ease for you soon!

Here are some other articles with relevant reading and links to useful exercises and interventions:

Teacher Burnout: 4 Warning Signs & How to Prevent It

How to Prevent Burnout in the Workplace: 20 Strategies

Warning Signs of Burnout: 13 Reliable Tests & Questionnaires

I wish you all the best!

– Nicole | Community Manager

This the best helpful burnout article I’ve read on the subject of burnout so thank you Alicia. Most articles offer child like simplistic responses like ooh do more exercise get plenty of sleep and rest. To someone who is so busy they haven’t got time to eat let alone cook it’s not helpful. This is the only article that acknowledges how long recovery takes and what the cures are. Most seem to dodge leaving your role or going to do something else.

I appreciated reading your article. I am currently on a short (2 week) medical leave relating to stress and burnout in my healthcare related field. Are you aware of any articles that you feel would be helpful to someone in my shoes? I work in radiation oncology where client emotions are always higher due to the nature of them being under our care. I feel that in “regular” times my work can be emotionally exhausting, never mind during a pandemic.

Hi SR,

I’m sorry to hear you’re experiencing burnout. Stress and burnout are common challenges in healthcare, and I can only imagine the increased challenges given the current pandemic.

I’d recommend taking a look at our article How to Prevent Burnout in the Workplace: 20 Strategies. In this article in particular, under the subheading ‘PositivePsychology.com’s Relevant Resources,’ you’ll find a list of useful resources about coping, stress management, and burnout (the latter four being free downloads).

In addition to the advice in this article, you may find some of the exercises useful to plan out helpful coping strategies and minimize the emotional exhaustion you experience in your work.

I hope this helps, and I wish you all the best.

– Nicole | Community Manager

Hi! I’m looking for recommendations for some type of retreat or inpatient treatment for this? Thinking 2-3 weeks and yes, I know that it will take much longer! I need a kick start to unravel my head. I feel overstimulated by everything.

I’m in stage 2 and headed to stage 3. I feel like I need to talk to some people experiencing the same thing so I can have someone to relate to.

I’m excited and ready for the long road to recovery. I could feel my heart, mind and body opening up after just a couple of weeks away from the work that I love, but I know is killing me….

Hi Kristie,

Sorry to read you’ve been struggling with burnout, but well done on taking steps to work through it. It’s hard for me to know what best to recommend as I’m not in a position to diagnose the severity of your burnout symptoms. Therefore, my suggestion would be to reach out to a counselor or therapist who will be able to properly assess the role of work in your life and deduce what strategies you can use to reduce that feeling of overstimulation and achieve better balance.

Psychology Today has a great directory you can use to find therapists in your local area. Usually, the therapists provide a summary in their profile with their areas of expertise and types of issues they are used to working with.

But besides those options, perhaps you could let me know where in the world you are located, and I can also see about retreats and similar group-based options available near you.

– Nicole | Community Manager

Dr. Nortje,

Thanks for the summary, much appreciated. I’m a professor and department chair. I’m on the second of three months of FMLA for burnout. Sleeping a lot now, not really sure how going back will work out. Do you have any advice on folks like professors who are super place bound?

Thanks!

Hi Elizabeth,

Glad you found this helpful, and thanks for sharing your experience. Academia is getting tougher with increasing demands being placed on faculty (let alone department chairs!) You might find this article in Nature helpful for validating your experience.

I hope this helps a little!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Makes complete sense and many recognisable factors – thank you. This is second time I’ve been off work due to burnout: this time I have now accepted that I may not be able to return to my workplace after a career of 32 years and there is no shame in this.

Great article Alicia. I think I am across stages 2 and 3 and that’s OK. It will take time to heal

I am glad to know that I may look for a different job, or perhaps just retire