Resilience Theory: A Summary of the Research (+PDF)

Life is never perfect. As much as we wish things would ‘just go our way,’ difficulties are inevitable and we all have to deal with them.

Life is never perfect. As much as we wish things would ‘just go our way,’ difficulties are inevitable and we all have to deal with them.

Resilience theory argues that it’s not the nature of adversity that is most important, but how we deal with it.

When we face adversity, misfortune, or frustration, resilience helps us bounce back. It helps us survive, recover, and even thrive in the face and wake of misfortune, but that’s not all there is to it.

Read on to learn about resilience theory in a little more depth, including its relationship with shame, organizations, and more.

But first, we thought you might like to download our three Resilience Exercises for free. These engaging, science-based exercises will help you to effectively deal with difficult circumstances and give you the tools to improve the resilience of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Resilience Theory?

- 6 Impactful Articles on Resilience and Mental Toughness

- What Research in Positive Psychology Shows

- Resilience Theory in Social Work

- Family Resilience Theory

- Shame Resilience Theory

- Community Resilience Theory

- Organizational Resilience Theory

- The ‘Science of Resilience’

- Norman Garmezy’s Main Findings and Contribution

- Seligman’s 3Ps Model of Resilience

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What Is Resilience Theory?

Resilience has been defined in numerous ways.

Defining resilience

The following definitions abound:

“the ability to bounce back from adversity, frustration, and misfortune”

Ledesma, 2014, p.1

“the developable capacity to rebound or bounce back from adversity, conflict, and failure or even positive events, progress, and increased responsibility”

Luthans, 2002a, p. 702

“a stable trajectory of healthy functioning after a highly adverse event”

Bonanno, 2004; Bonanno, Westphal, & Mancini, 2011

“the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully”

Masten, 2014; Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yehuda, 2014

When a panel discussion asked researchers to debate the nature of resilience, all agreed that resilience is complex. As a construct, it can have a different meaning between people, companies, cultures, and society. They also agreed that people could be more resilient at one point in their lives and less during another, and that they may be more resilient in some aspects of their lives than others (Southwick et al., 2014).

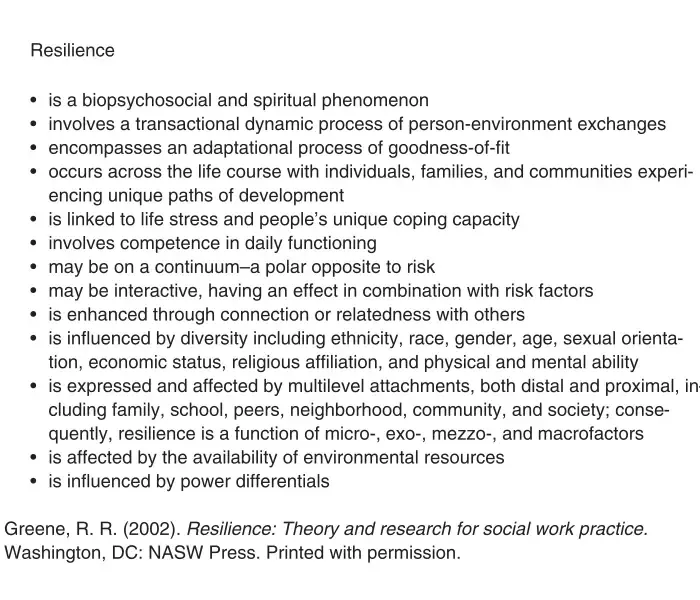

In case you’re interested, the table below from Greene, Galambos, and Lee (2004) shows even more ways resilience has been described.

Resilience theory

Resilience as a concept is not necessarily straightforward, and there are many operational definitions in existence. Resilience theory, according to van Breda (2018, p. 1), is the study of the things that make this phenomenon whole:

Its definition;

What ‘adversity’ and ‘outcomes’ actually mean, and;

The scope and nature of resilience processes.

6 Impactful Resilience Articles on Resilience and Mental Toughness

Ready to learn a bit more about resilience theory? For those who are keen to dig into the literature, this list demonstrates precisely how widely the concept can be applied: in social work, organizations, childhood development contexts, and more. You’ll find the full citations for these papers in the Reference section at the end of this article.

1. A Critical Review of Resilience Theory and Its Relevance for Social Work

In this literature review, Adrian van Breda (2018) considers peer-reviewed articles on resilience in the field of social work, discussing the evolution of an (as-yet to be established) consensus on its definition. He considers how it works and developments in the theory, looking at the study of resilience in South African cultures and societies.

2. Resilience Theory and Research on Children and Families: Past, Present, and Promise

Masten is known for her work on resilience and its role in helping families and children deal with adversity. In this article, she defines resilience as “the capacity of a system to adapt successfully to significant challenges that threaten its function, viability, or development” (Masten, 2018, p. 1).

Masten delves into the theory’s history and its research in this field in an attempt to integrate applications, models, and knowledge that may help children and their families grow and adjust.

3. Family Resilience: A Developmental Systems Framework

Professor Froma Walsh, cofounder of the Chicago Center for Family Health, has written extensively on family resilience and the positive adaptation of family units. In Family Resilience: A Developmental Systems Framework, Walsh (2016) considers the key processes in family resilience and gives a great overview of the concept from a family systems perspective.

4. Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach

Berkes and Ross (2013) examined two distinct approaches to understanding community resilience: a social-ecological approach and a mental health and developmental psychology perspective. This article, which we unpack a little more further on, is a great read for anyone with an academic interest in the growing research on resilience at the community level.

5. Organizational Resilience: Towards a Theory and Research Agenda

Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007) attempted to define organizational resilience and examine its underpinning mechanisms. Their paper considers the relational, cognitive, structural, and affective elements of the construct before proposing some research questions for those with an academic interest in the topic.

6. Are Adolescents With High Mental Toughness Levels More Resilient Against Stress?

While there are plenty of sports psychology articles that examine mental toughness, it’s not often you come across academic papers that consider its importance in other areas. Gerber et al. (2013) investigated whether mentally tough adolescents are resilient to stress, finding that mental toughness plays a mitigating role between high stress and depressive symptoms.

What Research in Positive Psychology Shows

Resilience and positive psychology are often closely related. Both are concerned with how promotive factors work, and both look at how a beneficial construct can facilitate our wellbeing (Luthar, Lyman, & Crossman, 2014).

Resilience theory and positive psychology are both applied fields of study, meaning that we can use them in daily life to benefit humanity, and both are very closely concentrated on the importance of social relationships (Luthar, 2006; Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2011).

So let’s look at what positive psychology research shows on resilience.

Character strengths and resilience

Strengths such as gratitude, kindness, hope, and bravery have been shown to act as protective factors against life’s adversities, helping us adapt positively and cope with difficulties such as physical and mental illness (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013).

Some character strengths can also be significant predictors of resilience, with particular correlations between resilience and emotional, intellectual, and restraint-related strengths (Martínez-Martí & Ruch, 2017).

In their 2017 study, Martínez-Martí and Ruch found that hope, bravery, and zest had the most extensive relationship with positive adaptation in the face of challenge. This led the researchers to speculate that processes such as determination, social connectedness, emotional regulation, and more were at play.

From this particular cross-sectional study, however, no causal relationship was determined. In other words, we don’t know whether resilience impacts our strengths or vice versa.

The effect may work the other way around with adversity, and post-traumatic growth helps us build character strengths, but nonetheless, it’s an example of resilience and positive psychology’s interconnection (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995; Peterson, Park, Pole, D’Andrea, & Seligman, 2008).

Resilience and positive emotions

Most people think of happiness whenever positive psychology is mentioned, so are happiness and resilience related? Cohn, Fredrickson, Brown, Mikels, and Conway (2009) suggested that they may well be. To be specific, happiness is a positive emotion.

According to the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, happiness is one emotion that helps us become more explorative and adaptable in our thoughts and behaviors. We create enduring resources that help us live well (Fredrickson, 2004).

Cohn et al. (2009) found that participants who frequently experienced positive emotions such as happiness grew more satisfied with their lives by creating resources, such as ego resilience, that helped them tackle a wide variety of challenges.

These results correspond with other evidence that positive emotions can facilitate resource growth and findings that link psychological resilience with physical health, psychological wellbeing, and positive affect (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005; Nath & Pradhan, 2012).

Its role in positive organizational behavior

Other studies have looked at resilience as one of numerous coping positive psychological resources, alongside optimism and hope.

Positive organizational behavior has been defined by Luthans (2002b, p. 59) as “the study and application of positively oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for performance improvement in today’s workplace.”

Can training employees help encourage positive organizational behavior? The jury is still out (Robertson, Cooper, Sarkar, & Curran, 2015).

Resilience Theory in Social Work

Some of the reasons for this are the central role of community relationships to both academic fields and the key social work principle that people should accept responsibility for one another’s wellbeing (International Federation of Social Workers, 2014).

One of the main drivers for more resilience theory research in social work contexts is the idea that identifying resilience-building factors can help at-risk clients in the following ways (Greene et al., 2004):

Promoting their competence and improving their health

Helping them overcome adversity and navigate life stressors

Boosting their ability to grow and survive

Concerning social workers, key issues in the field include:

Identifying protective factors and using them to inform interventions

Using practical applications to promote the capacity and strength of individual clients, societies, and communities

Understanding how social work policy and services promote or hinder wellbeing and social and economic injustice

Social work strategies for building client resilience

Greene et al.’s (2004) research also investigated the strategies and skills social workers relied on to boost the resilience of their clients. Some of these included:

Providing clients with safety and necessities when faced with adversity or traumatic events; for example, talking calmly with distressed individuals, reassuring them of their capabilities and ability to get through their troubles.

Listening, being present and honest, and learning from individuals’ stories while acknowledging their pain.

Promoting interpersonal relationships, attachments, and connections between people in a community or society.

Encouraging them to view themselves as a valued member of society.

Modeling resilient behaviors, such as dealing with work stress in healthy ways.

Realizing Resilience Masterclass

For social workers, therapists, and educators, an immense benefit can be gained from being able to boost your client’s resilience. To do so, enrolling in our Realizing Resilience Masterclass course would equip you to strengthen others, guide them, and teach them the six pillars of resilience.

This masterclass, based on scientific techniques, will provide you with all the material you need to deliver exceptional resilience training sessions. It is the ultimate shortcut to help others become more resilient. For more information, view our Realizing Resilience Masterclass page.

Shame resilience – Noor Pinna

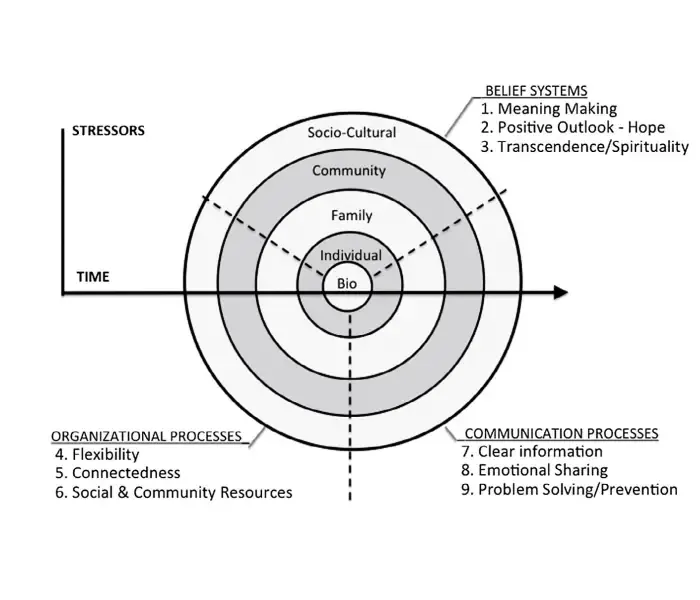

Family Resilience Theory

Family resilience has been defined in several ways. One way of viewing the construct is as the “characteristics, dimensions, and properties of families which help families to be resistant to disruption in the face of change and adaptive in the face of crisis situations’’ (McCubbin & McCubbin, 1988, p. 247).

Another more recent definition describes it as the “capacity of the family, as a functional system, to withstand and rebound from stressful life challenges – emerging strengthened and more resourceful’’ (Walsh, 1996; 2003; 2016).

Both of these definitions take the concept of individual psychological or emotional resilience and apply it at a broader level; one of the key areas that interests researchers is how families respond immediately when faced with challenges and over the longer term (Walsh, 2016).

Family resilience processes

In a meta-analysis on family resilience, Walsh (2003) proposed that the concept involves nine dynamic processes that interact with one another and help families strengthen their ties while developing more resources and competencies.

- Making sense of adversity – e.g., normalizing distress and contextualizing it, viewing crises as manageable and meaningful

- Having a positive outlook – e.g., focusing on potential, having hope and optimism

- Spirituality and transcendence – e.g., growing positively from adversity and connecting with larger values

- Flexibility – e.g., reorganizing and restabilizing to provide predictability and continuity

- Connectedness – e.g., providing each other with mutual support and committing to one another

- Mobilizing economic and social resources – e.g., creating financial security and seeking support from the community at large

- Clarity – e.g., providing one another with information and consistent messages

- Sharing emotions openly – including positive and painful feelings

- Solving problems collaboratively – e.g., through joint decision-making, a goal-focus, and building on successes

Shame Resilience Theory

The theory attempts to study how we respond to and defeat shame, an emotion we all experience. Brown (2008) describes shame resilience theory as the ability to recognize this negative emotion when we feel it and overcome it constructively in such a way that we can “retain our authenticity and grow from our experiences.”

Read more about shame resilience theory in this excellent article: Shame Resilience Theory: How to Respond to Feelings of Shame.

Community Resilience Theory

A community resilience concept

Magis (2010, p. 401) defined community resilience as the ”existence, development and engagement of community resources by community members to thrive in an environment characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability, and surprise.”

In other words, one approach to defining community resilience emphasizes the importance of individual mental health and personal development on a social system’s capacity to unite and collaborate toward a shared goal or objective (Berkes & Ross, 2013).

The key focus of community resilience is on identifying and developing both individual and community strengths and establishing the processes that underpin resilience-promoting factors (Buikstra et al., 2010). Its goals also include understanding how communities leverage these strengths together to facilitate self-organization and agency, which then contributes to a collective process of overcoming challenges and adversity (Berkes & Ross, 2013).

Community resilience is considered an ongoing process of personal development in dealing with adversity through adaptation and understandably plays a vital role in social work contexts (Almedom, Tesfamichael, Mohammed, Mascie-Taylor, & Alemu, 2007).

Relevant research questions related to community resilience theory include (Berkes & Ross, 2013):

- What are the characteristics of individual and community resilience, and how can these be fostered (Buikstra et al., 2010)?

- How is community resilience related to health, and how are health professionals able to help (Kulig, 2000; Kulig, Edge, & Joyce, 2008; Kulig, Hegney, & Edge, 2010)?

- How can community resilience improve readiness for disaster (Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche, & Pfefferbaum, 2008)?

Community strengths promoting resilience

While community strengths vary between groups, Berkes and Ross (2013) identified a few characteristics that have a central role in helping communities develop resilience. These strengths, processes, and attributes include:

- Social networks and support

- Early experience

- People–place connections

- Engaged governance

- Community problem-solving

- Ability to cope with divisions

Organizational Resilience Theory

Just as people can develop their resilience, organizations can learn to rebound from and adapt after facing challenges. Organizational resilience can be thought of as “a ‘culture of resilience,’ which manifests itself as a form of ‘psychological immunity’” to incremental and transformational changes, according to Boston Consulting Group Fellow Dr. George Stalk, Jr. (Everly, 2011).

With a host of factors contributing to a dynamic and sometimes turbulent business environment, organizational resilience has gained incredible salience in recent years. And at the heart of it, Everly argues, are optimism and perceived self-efficacy.

How to build organizational resilience

A culture of organizational resilience relies heavily on role-modeling behaviors. Even a few credible and high-profile individuals in a company demonstrating resilient behaviors may encourage others to do the same (Everly, 2011).

These behaviors include:

- Persisting in the face of adversity

- Putting effort into dealing with challenges

- Practicing and demonstrating self-aiding thought patterns

- Providing support to and mentoring others

- Leading with integrity

- Practicing open communication

- Showing decisiveness

Read more about Positive Organizations here.

InBrief: the science of resilience

The ‘Science of Resilience’

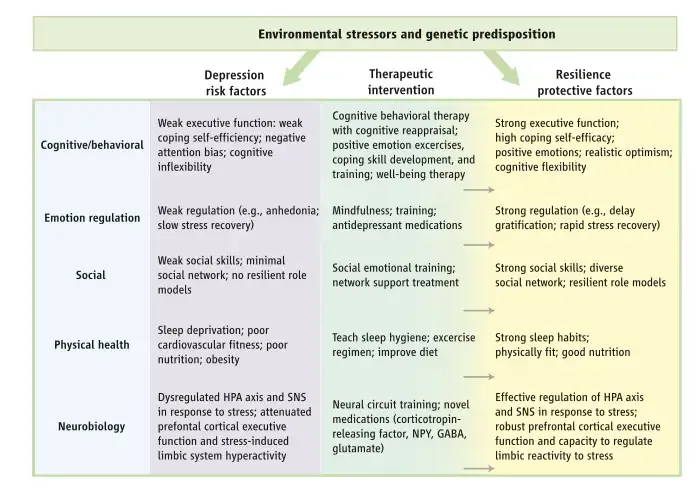

Are some people born more resilient than others? Southwick and Charney (2012) discussed human biological responses to trauma and looked at a sample of high-risk individuals to understand why some are more able to cope even in the face of life-changing adversity.

They examined three samples of participants to investigate whether these individuals had a genetic predisposition toward being more resilient:

- Special Forces instructors

- Vietnam prisoners of war

- Individuals who had suffered considerable trauma

Southwick and Charney (2012) looked at the psychological factors of these individuals; their genetic factors; and their spiritual, social, and biological factors.

The results:

Risk and protective factors generally have additive and interactive effects… having multiple genetic, developmental, neurobiological, and/or psychosocial risk factors will increase allostatic load or stress vulnerability, whereas having and enhancing multiple protective factors will increase the likelihood of stress resilience.

Put succinctly, genetic factors do have an important influence on our responses to trauma and stress. The image below gives a good overview of their findings.

Source: Southwick & Charney, 2012, p. 81

In the article, mentioned in our References section, you can learn more about two key concepts that are central to resilience theory:

- Learned helplessness – where individuals believe they are incapable of changing or controlling their circumstances after repeatedly experiencing a stressful event

- Stress inoculation – whereby they can develop an “adaptive stress response and become more resilient than normal to the negative effects of future stressors” (Southwick & Charney, 2012, p. 80)

Norman Garmezy’s Main Findings and Contribution

University of Minnesota developmental psychologist Norman Garmezy is one of the best-known contributors to resilience theory as we know it. His seminal work on resilience focused on how we could prevent mental illness through protective factors such as motivation, cognitive skills, social change, and personal ‘voice’ (Garmezy, 1992).

His pioneering work included the Project Competence Longitudinal Study (PCLS), which contributed operational definitions, frameworks, measures, and more to the study of competence and resilience. Started around 1974, the PCLS was developed to enable more structured and rigorous resilience research and look into protective buffers that help children overcome adversity (Masten & Tellegen, 2012).

One of its more impactful discoveries was that resilience is a dynamic construct that changes over time; another was the concept of developmental cascades, which describe how functioning in one domain can influence other levels of adaptive function.

If you’re curious to find out more about the work of Norman Garmezy, Masten and Tellegen’s (2012) paper is a great read: Resilience in Developmental Psychopathology: Contributions of the Project Competence Longitudinal Study.

Seligman’s 3Ps Model of Resilience

The best-known positive psychology framework for resilience is Seligman’s 3Ps model.

These three Ps – personalization, pervasiveness, and permanence – refer to three emotional reactions that we tend to have to adversity. By addressing these three, often automatic, responses, we can build resilience and grow, developing our adaptability and learning to cope better with challenges.

The 3Ps

Seligman’s (1990) 3Ps are:

Personalization – a cognitive distortion that’s best described as the internalization of problems or failure. When we hold ourselves accountable for bad things that happen, we put a lot of unnecessary blame on ourselves and make it harder to bounce back.

Pervasiveness – assuming negative situations spread across different areas of our life; for example, losing a contest and assuming that all is doom and gloom in general. By acknowledging that bad feelings don’t impact every life domain, we can move forward toward a better life.

Permanence – believing that bad experiences or events last forever, rather than being transient or one-off events. Permanence prevents us from putting effort into improving our situation, often making us feel overwhelmed and as though we can’t recover.

These three perspectives help us understand how our thoughts, mindset, and beliefs affect our experiences. By recognizing their role in our ability to adapt positively, we can start becoming more resilient and learn to bounce back from life’s challenges.

A Take-Home Message

Resilience is something we can all develop, whether we want to grow as individuals, as a family, or as a society more broadly. If you’re interested in developing your psychological resilience, our Realizing Resilience Masterclass uses science-based tools and techniques to help you understand the concept better and cultivate more “bounce-back.”

Or, if you’re hoping to read more about the topic in general, we’ve got a vast range of blog posts, worksheets, and activities in our Resilience & Coping section on this site. Before you go, though, tell us, what interests you most about resilience theory and what fields have you been applying it in professionally?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Resilience Exercises for free.

- Almedom, A. M., Tesfamichael, B., Mohammed, Z. S., Mascie-Taylor, C. G. N., & Alemu, Z. (2007). Use of ‘sense of coherence (SOC)’ scale to measure resilience in Eritrea: Interrogating both the data and the scale. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(1), 91–107.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely adverse events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28.

- Bonanno G. A., Westphal, M., & Mancini, A. D. (2011). Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 511–535.

- Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society & Natural Resources, 26(1), 5–20.

- Brown, B. (2006). Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory study on women and shame. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87(1), 43–52.

- Brown, B. (2008). I thought it was just me (but it isn’t). Avery.

- Buikstra, E., Ross, H., King, C. A., Baker, P. G., Hegney, D., McLachlan, K., & Rogers-Clark, C. (2010). The components of resilience: Perceptions of an Australian rural community. Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 975–991.

- Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9(3), 361–368.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (2011). Positive psychology: Where did it come from, where is it going? In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 3–8). Oxford University Press.

- Everly, G. S. (2011). Building a resilient organizational culture. Harvard Business Review, 10(2), 109–138.

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience. European Psychologist, 18, 12–23.

- Fredrickson, B. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society B, 359(1449), 1367–1377.

- Garmezy, N. (1992). Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. Cambridge University Press.

- Gerber, M., Kalak, N., Lemola, S., Clough, P. J., Perry, J. L., Pühse, U., … Brand, S. (2013). Are adolescents with high mental toughness levels more resilient against stress? Stress and Health, 29(2), 164–171.

- Greene, R. R., Galambos, C., & Lee, Y. (2004). Resilience theory: Theoretical and professional conceptualizations. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 8(4), 75–91.

- International Federation of Social Workers. (2014). Global definition of social work: Principles. Retrieved from https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

- Kulig, J. C. (2000). Community resiliency: The potential for community health nursing theory development. Public Health Nursing, 17, 374–385.

- Kulig, J. C., Edge, D. S., & Joyce, B. (2008). Understanding community resiliency in rural communities through multimethod research. Journal of Rural Community Development, 3, 76–94.

- Kulig, J. C., Hegney, D., & Edge, D. S. (2010). Community resiliency and rural nursing: Canadian and Australian perspectives. In C. A. Winters & H. J. Lee (Eds.), Rural nursing: Concepts, theory and practice (3rd ed.) (pp. 385–400). Springer.

- Ledesma, J. (2014). Conceptual frameworks and research models on resilience in leadership. Sage Open, 4(3), 1–8.

- Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed.) (pp. 739–795). Wiley.

- Luthar, S. S., Lyman, E. L., & Crossman, E. J. (2014). Resilience and positive psychology. In M. Lewis & K. D. Rudolph (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychopathology (pp. 125–140). Springer Science + Business Media.

- Luthans, F. (2002a). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 695–706.

- Luthans, F. (2002b). Positive organizational behavior. Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 57–72.

- Lyubomirsky, S. L., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 14, 803–855.

- Magis, K. (2010). Community resilience: An indicator of social sustainability. Society & Natural Resources, 23, 401–416.

- Martínez-Martí, M. L., & Ruch, W. (2017). Character strengths predict resilience over and above positive affect, self-efficacy, optimism, social support, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(2), 110–119.

- Masten A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85, 6–20.

- Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 12–31.

- Masten, A. S., & Tellegen, A. (2012). Resilience in developmental psychopathology: Contributions of the project competence longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 345–361.

- McCubbin, L. D., & McCubbin, H. I. (1988). Typologies of resilient families: Emerging roles of social class and ethnicity. Family Relations, 37(3), 247–254.

- Nath, P., & Pradhan, R. K. (2012). Influence of positive affect on physical health and psychological well-being: Examining the mediating role of psychological resilience. Journal of Health Management, 14(2), 161–174.

- Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capabilities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 127–150.

- Peterson, C., Park, N., Pole, N., D’Andrea, W., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2008). Strengths of character and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 214–217.

- Robertson, I. T., Cooper, C. L., Sarkar, M., & Curran, T. (2015). Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 533–562.

- Seligman, M. (1990). Learned optimism. Pocket Books.

- Southwick, S. M., & Charney, D. S. (2012). The science of resilience: implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. Science, 338(6103), 79–82.

- Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25338.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1995). Trauma & transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Sage.

- Van Breda, A. D. (2018). A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Social Work, 54(1), 1–18.

- Vogus, T. J., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Organizational resilience: Towards a theory and research agenda. In 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (pp. 3418–3422). IEEE.

- Walsh, F. (1996). The concept of family resilience: Crisis and challenge. Family Process, 35, 261–281.

- Walsh, F. (2003). Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42, 1–18.

- Walsh, F. (2016). Family resilience: a developmental systems framework. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 313–324.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (54)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (39)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (44)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (13)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (41)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (13)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)

What our readers think

Very good and interesting………….

This is a terrific summary of a complex area. Connect with me on LinkedIn please – I’m writing in this field also.