Albert Bandura: Self-Efficacy & Agentic Positive Psychology

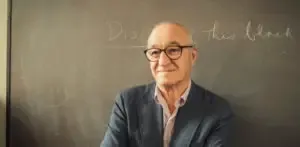

Prof. Albert Bandura is one of the most highly cited academics in the world (Haggbloom et al., 2002).

Prof. Albert Bandura is one of the most highly cited academics in the world (Haggbloom et al., 2002).

Bandura’s scholarship has formed part of many enduring branches of psychology, including social cognitive theory, reciprocal determinism, and social learning theory.

The principles stemming from this scholar’s work have informed policies around the world (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2003) and are at the core of many cognitive-behavioral psychology interventions.

Having received prestigious awards from several notable organizations, including a National Medal of Science from former President Barack Obama, many would be surprised to learn that Bandura’s work began from humble beginnings.

More specifically, it all began with an inflatable clown named Bobo. In his lab, Bandura observed that children who witnessed adults beating up Bobo the clown were more likely to do so themselves. Findings based on this observation became a research movement, now known as social learning theory, demonstrating that learning can occur through imitation and social modeling (Bandura & Walters, 1977).

Our understanding of the human experience, behavior, and psychology has advanced significantly as a result of Bandura’s work. Most notably, his research on social cognitive theory and the specific concept of self-efficacy serve as the bedrock for much of our ongoing work as positive psychologists (Bandura, 2008).

Since self-compassion can help foster self-efficacy, you might like to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free before we continue. These detailed, science-based exercises will not only help you increase the compassion and kindness you show yourself but will also give you the tools to help your clients, students or employees show more compassion to themselves.

This Article Contains:

An Agentic Perspective on Positive Psychology

There are many excellent works in which Bandura discusses his views of agency. An Agentic Perspective on Positive Psychology (Bandura, 2008) and his piece in the Annual Review of Psychology (Bandura, 2001) are two starting points.

In his writings, Bandura challenges early behavioristic thinking that took a simplistic view of the human mind and experience. According to this view, it was thought that humans function like input-output systems, whereby external stimuli exert their effects, resulting in a specific unvarying response (like a machine that lights up whenever a particular button is pressed).

Nowadays, psychologists wouldn’t dream of treating the human experience so simplistically. Yet, the idea that humans are at the whim of their environment and circumstances was, at one point, dominant thinking.

Thanks to Bandura’s work, psychologists now recognize that humans are the agents of their self-development, who can adapt and self-regulate to achieve their desired future (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2003). But achieving this paradigm shift in thinking has required the dismantling of many existing schools of thought.

For one, Bandura critiques the predominantly negative and pathology-focused approach in the discipline of psychology. This “disease model” approach contrasts with positive psychology’s pro-self-efficacy approach, in which humans can exert control over their failings and dysfunction (Bandura, 2008).

Similarly, agency and self-efficacy have shaped beliefs around other key experiences, such as that of optimism and realism. Before Bandura’s work, psychologists did not see the value of optimism, especially in situations where a person’s chances of achieving a desired outcome were low. Now, thanks to Bandura’s work, the ability to maintain optimism in the face of tough odds is recognized as being key to success in many roles.

To quote George Bernard Shaw:

The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.

George Bernard Shaw (Goodreads)

What’s inspiring is that self-efficacy can be developed by anyone. That is, self-efficacy is not a trait that some have, and others do not. Rather, everyone can exercise agency and strengthen their self-efficacy, regardless of their past or current environment (Schunk & Ertmer, 2000).

4 Ways to Build Self-Efficacy

Bandura evidences four ways to develop self-efficacy across the breadth of his research.

1. Mastery Experiences

Bandura (2008) argues that the most effective way to build self-efficacy is through mastery experiences.

There is no better way to start believing in one’s ability to succeed than to set a goal, persist through challenges on the road to goal-achievement, and enjoy the satisfying results. Once a person has done this enough times, they will come to believe that sustained effort and perseverance through adversity will serve a purpose in the end; belief in one’s ability to succeed will grow.

In contrast, regularly achieving easy success with little effort can lead people to expect rapid results, which can result in their being easily discouraged by failure (Bandura, 2008).

The importance of mastery experiences becomes poignant when we consider it in the context of parenting and early developmental experiences. As a parent, there is a strong temptation to prevent a child from ever experiencing failure (sometimes referred to as ‘snowplow parenting’).

However, a child who doesn’t learn to overcome disappointment and draw upon their internal resources to push through obstacles will miss out on opportunities to develop their self-efficacy. Consequently, the child may be left under-equipped when it comes to handling the challenges that await them in adulthood.

Experiencing failure is important so that we can build resilience. This is done by treating every failure as a learning opportunity and a chance to reach competence via a different approach.

2. Social Modeling

Another way that a person can build self-efficacy is by witnessing demonstrations of competence by people who are similar to them (Bandura, 2008). In this scenario, the person witnessing the display of competence perceives aspects of their own identity in the actor. That is, the actor may be of a similar age, ethnic background, sexuality, or gender as the observer (Bandura, 1997).

The observer, who witnesses the actor’s success through dedicated efforts, will be inspired to believe that they, too, can achieve their goals.

When we consider the power of role modeling for inspiring self-belief, we can begin to understand the importance of diverse representation in the media. In the past, one would have needed to find a role-model in one’s immediate social surroundings. Now, through the internet and other digital mediums, people (especially young people) are being exposed to many potential role-models.

If these viewers never see anyone like themselves displaying acts of competence across the various domains of life (e.g., speaking in the media, competing in elite sports), they are denied the opportunity to develop self-efficacy through this vicarious modeling and may be less likely than other populations to pursue their ambitions.

3. Social Persuasion

When a person is told that they have what it takes to succeed, they are more likely to achieve success. In this way, self-efficacy becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy (Eden & Zuk, 1995).

While not as powerful as mastery for strengthening self-efficacy (Bandura, 2008), being told by someone we trust that we possess the capabilities to achieve our goals will do more for us than dwelling on our deficiencies.

Therefore, a good mentor can boost self-efficacy not only through role-modeling but by serving as a trusted voice of encouragement. They may also help their mentee to recognize opportunities in which they can demonstrate competence (without being overwhelmed) and persuade them to step into the ring.

Other works (beyond those of Bandura) have even investigated the role of self-talk for strengthening self-efficacy and improving performance. For instance, one study found that tennis players who gave themselves a motivational pep talk before practicing a particular swing performed significantly better than a group who did not give themselves a pep talk (Hatzigeorgiadis, Zourbanos, Goltsios, & Theodorakis, 2008).

This finding suggests that we can verbally persuade ourselves to believe in our capabilities and strengthen our self-efficacy.

4. States of Physiology

Lastly, our emotions, moods, and physical states influence how we judge our self-efficacy (Kavanagh & Bower, 1985).

According to Bandura (2008), it is harder to feel assured of our ability to succeed when we feel weariness and a low mood. This is especially true if we perceive these emotional and physiological states to be indicative of our incompetence, vulnerability, or inability to achieve a goal.

Introspection and education can prevent these physical states from being interpreted negatively. For example, when experiencing a personal or work-related failure, people can practice self-compassion.

At chronic levels, low mood can have a debilitating effect on self-efficacy and subsequent goal achievement, as people with chronically low mood are likely to give up on goals sooner and demonstrate a reluctance to even take up goals in the first place (Bandura, 2008).

Indeed, it’s been shown that while people suffering from depression still have goals, they hold more pessimistic beliefs about their ability to achieve goals successfully and perceive that they have less control over the outcomes of goals (Dickson, Moberly, & Kinderman, 2011).

In sum, changing negative misinterpretations of physical and affective states is key to build self-efficacy (Bandura, 2008).

The strength self-efficacy scale is one tool which can help build insight and introspection, and alleviate the need for judging ourselves too harshly when we make mistakes.

How Self-Efficacy Can Influence You

In his discussion of agency’s links to positive psychology, Bandura (2008) explains how self-efficacy exerts its effects through four different internal processes.

Cognitive Processes

Thinking in self-enhancing (optimistic) or self-debilitating (pessimistic) ways can influence one’s functioning (Bandura, 1994; 2008).

If someone believes that their actions impact their experience and the environment, they are more prone to a self-sustaining optimistic view. In other words, no matter what the circumstance is, ‘something’ can be done to affect the ultimate outcome.

Without this belief, a more pessimistic thought process can dominate, and events might be interpreted as ‘out-of-my-hands.’ When the individual is a passenger in the ride that is their life, there is no room for agency.

Motivational

Self-efficacy means believing in the value of motivation to influence any outcome. If someone does not feel driven to alter an event, they are less likely to exert effort toward producing a particular outcome — particularly in the face of obstacles. To do so would be perceived as a waste of energy (Bandura, 1994).

Thus, feeling secure in one’s self-efficacy leads to self-determined motivation. Goal pursuit becomes not a question of “can I reach my goal?” but rather, “what is required for me to reach my goal?”

Often, collective self-efficacy needs to be considered. That is, what does a group believe they can achieve in terms of a common goal? To use Bandura’s (2008, p. 3) words: “People’s shared belief in their collective efficacy to achieve desired results is a key ingredient of collective agency.”

Emotional

While states of physiology (such as our moods) influence self-efficacy, the reverse is true as well — self-efficacy can affect our emotions (Heuven, Bakker, Schaufeli, & Huisman, 2006).

A healthy sense of self-efficacy helps us to not be at the mercy of our negative emotional states that stem from failures and disappointment. Instead, we rise from the ashes of our failures gracefully, with a healthy dose of optimism and resilience; we believe that we can ‘bounce back.’

A determination not to let our negative emotions block our future efforts is a critical outcome of self-efficacy — one that relates closely to the concept of emotional intelligence.

Decisional

Self-efficacy also feeds into our decision-making processes when it comes to exposing ourselves to different environments and situations (Mun & Hwang, 2003).

As noted, Bandura’s view of the agentic human experience argues that humans have control over their self-development. The alternative is that humans’ lives are at the whim of destiny. Therefore, by employing self-efficacy, one can choose to expose themselves to environments that will best facilitate personal growth and development through thoughtful choices and deliberate actions (Bandura, 2008).

Pathologizing Optimism: Visions to Realities

As noted, early psychologists have often likened optimism to pathology and argued that a realist perspective is best for psychological wellness. Indeed, before Bandura came onto the scene, overconfidence had been studied extensively (see Moore & Healy, 2008), and the costs of self-limiting beliefs had largely been ignored.

Bandura (2008) proposes that while realism is useful when risks are high and failure is likely, it can often hinder progress. He goes on to argue that optimism and a resilient sense of self-efficacy are vital to overcoming even the realities of daily life, which can include frustrations, setbacks, conflict, and failure.

To succeed, Bandura says, one cannot afford to be a realist (Bandura, 2008, p. 1). Thus, in situations where time, effort, and resources are the tradeoffs, optimism can provide the appropriate self-efficacy to achieve otherwise unreachable goals.

For further reading on this topic, we suggest What Is Pathologizing & Overpathologizing in Psychology?

Misconceptions about Self-Efficacy

Addressing the skepticism of self-efficacy, Bandura argues that, contrary to what some researchers may think, the concept has little to do with self-centeredness or selfishness.

Self-Efficacy is Not Selfish

Highlighting Gandhi’s self-sacrifice as an example of his “unwavering self-efficacy for social change under powerful opposition,” Bandura (2008, p. 4) explains that self-efficacy can actually uplift society. He also states that when people lack resilient self-efficacy, they are likely to be so overwhelmed by personal adversity that making efforts to improve the lives of others will overstretch individual capacities.

In contrast, a person with a good supply of self-efficacy will have a greater ability to manage the demands in their own life and, therefore, have the ability to help others.

How Self-Efficacy can Help Overcome Environment

Some psychopathology theories deem inner-city populations as highly vulnerable to negative life outcomes (e.g., mental illness, criminal behaviors). However, Bandura (2008) argues that self-efficacy may serve to guard an individual against the impact of adverse environmental influences, enabling people to lead fulfilling lives despite their past or current environments.

In such environments, self-efficacy can be developed through positive role-modeling and effective use of one’s social networks to enable progress and fulfillment.

This thinking calls into question the logic of the diathesis-stress model, which argues that the experience of stress (and its negative consequences) is unavoidable when a person who is vulnerable to stress is over-exposed to negative external stimuli (Meehl, 1962). Bandura (2008) believes that this model disregards how people may employ their agency to manage stress (and negate the harm of its consequences).

Self-Efficacy and Substance Abuse

In the case of substance abuse, specifically smoking, Bandura (2008) goes through the proposed biological and psychological mechanisms inhibiting those who wish to quit their addiction.

In doing so, he makes a strong case for self-efficacy as a mediating factor, influencing smokers’ attempts to quit. While Bandura does not dismiss the relevance of biological and psychological mechanisms involved in quitting, he emphasizes that the majority of ex-smokers who stop their nicotine addiction do so without outside aid. This implies that it is a factor internal to the individual that leads to the successful cessation of smoking — namely, self-efficacy.

Indeed, evidence has found that high self-efficacy increases the likelihood that a person will successfully quit nicotine (Garcia, Schmitz, & Doerfler, 1990) and may also aid the addiction rehabilitation process.

Health Promotion

In his chapter on positive psychology, Bandura (2008) reflects on gaps in existing medical systems and the role that self-efficacy may play in preventative health initiatives. Bandura observes that research predominantly focuses on what and how things go ‘wrong’ in the human body, rather than the ways that healthy lifestyle choices can be promoted to enable thriving and prevent such problems occurring in the first place.

Self-efficacy is key to encouraging healthy lifestyle choices (e.g., healthy stress management, regular physical activity). This is because a person who does not believe they can influence their health outcomes via their choices is unlikely to even try.

The implication is that there is value in research that examines how self-efficacy beliefs related to influencing one’s personal health outcomes can be strengthened.

Want to Know More about Albert Bandura?

Find out more about Albert Bandura’s life, or read his review on social cognitive theory.

We also recommend watching his interview with the Association for Psychological Science to learn more about Bandura’s early research and journey to becoming one of the world’s most influential psychologists.

For those who were inspired by these highlights from An Agentic Perspective of Positive Psychology by Albert Bandura (2008), the full chapter is freely available online if you would like to read the work in full.

A Take-Home Message

If we are to take anything away from Bandura’s work, it is that self-efficacy is a key driver of success across all domains of life. While there may be a temptation to roll one’s eyes at the notion of ‘believing in ourselves’ or ‘trusting in our abilities,’ it is important to remember that there is a great deal of research behind these encouraging messages.

For a long time, to endorse optimism when calculating the odds of success under trying circumstances would appear unwise. Now, it is common to encourage others to pursue their ambitions with optimism and determination in spite of potential challenges, largely thanks to the paradigm shift that spawned from Bandura’s work.

By enabling us to master our thoughts, motivations, emotions, and decisions, self-efficacy is key to recognizing our ability to shape the world around us.

To face life without self-efficacy is to narrow one’s options when navigating the often daunting obstacles of life. Therefore, conducting more research and identifying ways to develop self-efficacy may be key to improving quality of life.

How do you balance optimistic and realistic outlooks when you pursue goals? We would love to read your ideas in our comments section.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Self Compassion Exercises for free.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In R. J. Corsini (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 368-369). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Behavior theory and the models of man (1974). In J. M. Notterman (Ed.), The evolution of psychology: Fifty years of the American Psychologist (pp. 154–172). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1-26.

- Bandura, A. (2008). An agentic perspective on positive psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Praeger perspectives. Positive psychology: Exploring the best in people (Vol. 1., pp. 167–196). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Dickson, J. M., Moberly, N. J., & Kinderman, P. (2011). Depressed people are not less motivated by personal goals but are more pessimistic about attaining them. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(4), 975-980.

- Eden, D., & Zuk, Y. (1995). Seasickness as a self-fulfilling prophecy: Raising self-efficacy to boost performance at sea. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(5), 628–635.

- Garcia, M. E., Schmitz, J. M., & Doerfler, L. A. (1990). A fine-grained analysis of the role of self-efficacy in self-initiated attempts to quit smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 317-322.

- Haggbloom, S. J., Warnick, R., Warnick, J. E., Jones, V. K., Yarbrough, G. L., Russell, T. M., … & Monte, E. (2002). The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Review of General Psychology, 6(2), 139-152.

- Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Zourbanos, N., Goltsios, C., & Theodorakis, Y. (2008). Investigating the functions of self-talk: The effects of motivational self-talk on self-efficacy and performance in young tennis players. The Sport Psychologist, 22(4), 458-471.

- Heuven, E., Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., & Huisman, N. (2006). The role of self-efficacy in performing emotion work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(2), 222-235.

- Kavanagh, D. J., & Bower, G. H. (1985). Mood and self-efficacy: Impact of joy and sadness on perceived capabilities. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 9(5), 507-525.

- Meehl, P. E. (1962). Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. American Psychologist, 17(12), 827–838.

- Moore, D. A., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115(2), 502-517.

- Mun, Y. Y., & Hwang, Y. (2003). Predicting the use of web-based information systems: self-efficacy, enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59(4), 431-449.

- Schunk, D. H., & Ertmer, P. A. (2000). Self-regulation and academic learning: Self-efficacy enhancing interventions. In Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 631-649). Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2003). Albert Bandura: The scholar and his contributions to educational psychology. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Educational psychology: A century of contributions (pp. 431–457). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (54)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (44)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (14)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (41)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (13)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)

What our readers think

can self efficacy moderate the relationship between social support and leadership behavior?

what is the best tool to measure self efficacy?

is self efficacy teachable? I believe yes, any well established interventions to teach it?

Hi Jane,

Regarding your second question, self-efficacy can certainly be taught. In fact, Bandura argues that there are four drivers of self-efficacy, one of which is mastery experiences (i.e., hands-on practice and experience with the focal behavior). Interventions (and the most appropriate measure) for self-efficacy depend on the specific behavior or type of performance you’re interested in, but mastery experiences tend to cut across all of these 🙂

Regarding your first question, I might need a little more information before I can advise. What specific types of leadership behavior are you interested in, and what kind of social support are you looking at (e.g., flowing from the leader? A subordinate?)

– Nicole | Community Manager

I was just wondering when this was originally published. For citation purposes.

Hi Rasheed,

The original post was published Jul 28, 2016. 🙂

– Nicole | Community Manager