19 Best Narrative Therapy Techniques & Worksheets [+PDF]

Imagine a narrative of your “life story” in which you are the hero of your own life, rather than the victim?

Imagine a narrative of your “life story” in which you are the hero of your own life, rather than the victim?

It is likely that the life story you tell yourself and others changes depending on who is asking, your mood, and whether you feel like you are still at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of your most salient story.

But when was the last time you paused to consider the stories you tell?

“What is your story?”

Narrative therapy capitalizes on this question and our storytelling tendencies. The goal is to uncover opportunities for growth and development, find meaning, and understand ourselves better.

We use stories to inform others, connect over shared experiences, say when we feel wronged, and even to sort out our thoughts and feelings. Stories organize our thoughts, help us find meaning and purpose, and establish our identity in a confusing and sometimes lonely world. Thus, it is important to realize what stories we are telling ourselves, and others, when we talk about our lives.

If you’ve never heard of narrative therapy before, you’re not alone!

This therapy is a specific and less common method of guiding clients towards healing and personal development. It’s revolves around the stories we tell ourselves and others.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What is Narrative Therapy? A Definition

- 5 Commonly Used Narrative Therapy Techniques

- 3 More Narrative Therapy Exercises and Interventions

- Examples of Questions to Ask Your Clients

- Narrative Therapy Treatment Plan

- Best Books on Narrative Therapy

- YouTube Videos for Further Exploration

- A Handy PowerPoint to Use

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Narrative Therapy? A Definition

Narrative therapy is a form of therapy that aims to separate the individual from the problem, allowing the individual to externalize their issues rather than internalize them.

It relies on the individual’s own skills and sense of purpose to guide them through difficult times (Narrative Therapy, 2017).

This form of therapy was developed in the 1980s by Michael White and David Epston (About Narrative Therapy, n.d.).

They believed that separating a person from their problematic or destructive behavior was a vital part of treatment (Michael White (1948-2008), 2015).

For example, when treating someone who had run afoul of the law, they would encourage the individual to see themselves as a person who made mistakes, rather than as an inherently “bad” felon. White and Epston grounded this new therapeutic model in three main ideas.

1. Narrative therapy is respectful.

This therapy respects the agency and dignity of every client. It requires each client to be treated as an individual who is not deficient, not defective, or not “enough” in any way.

Individuals who engage in narrative therapy are brave people who recognize issues they would like to address in their lives.

2. Narrative therapy is non-blaming.

In this form of therapy, clients are never blamed for their problems, and they are encouraged not to blame others as well. Problems emerge in everyone’s lives due to a variety of factors; in narrative therapy, there is no point in assigning fault to anyone or anything.

Narrative therapy separates people from their problems, viewing them as whole and functional individuals who engage in thought patterns or behavior that they would like to change.

3. Narrative therapy views the client as the expert.

In narrative therapy, the therapist does not occupy a higher social or academic space than the client. It is understood that the client is the expert in their own life, and both parties are expected to go forth with this understanding.

Only the client knows their own life intimately and has the skills and knowledge to change their behavior and address their issues (Morgan, 2000).

These three ideas lay the foundation for the therapeutic relationship and the function of narrative therapy. The foundation of this therapeutic process has this understanding and asks clients to take a perspective that may feel foreign. It can be difficult to place a firm separation between people and the problems they are having.

Key Concepts and Approach

Making the distinction between “an individual with problems” and a “problematic individual” is vital in narrative therapy. White and Epston theorized that subscribing to a harmful or adverse self-identity could have profound negative impacts on a person’s functionality and quality of life.

“The problem is the problem, the person is not the problem.”

Michael White and David Epston

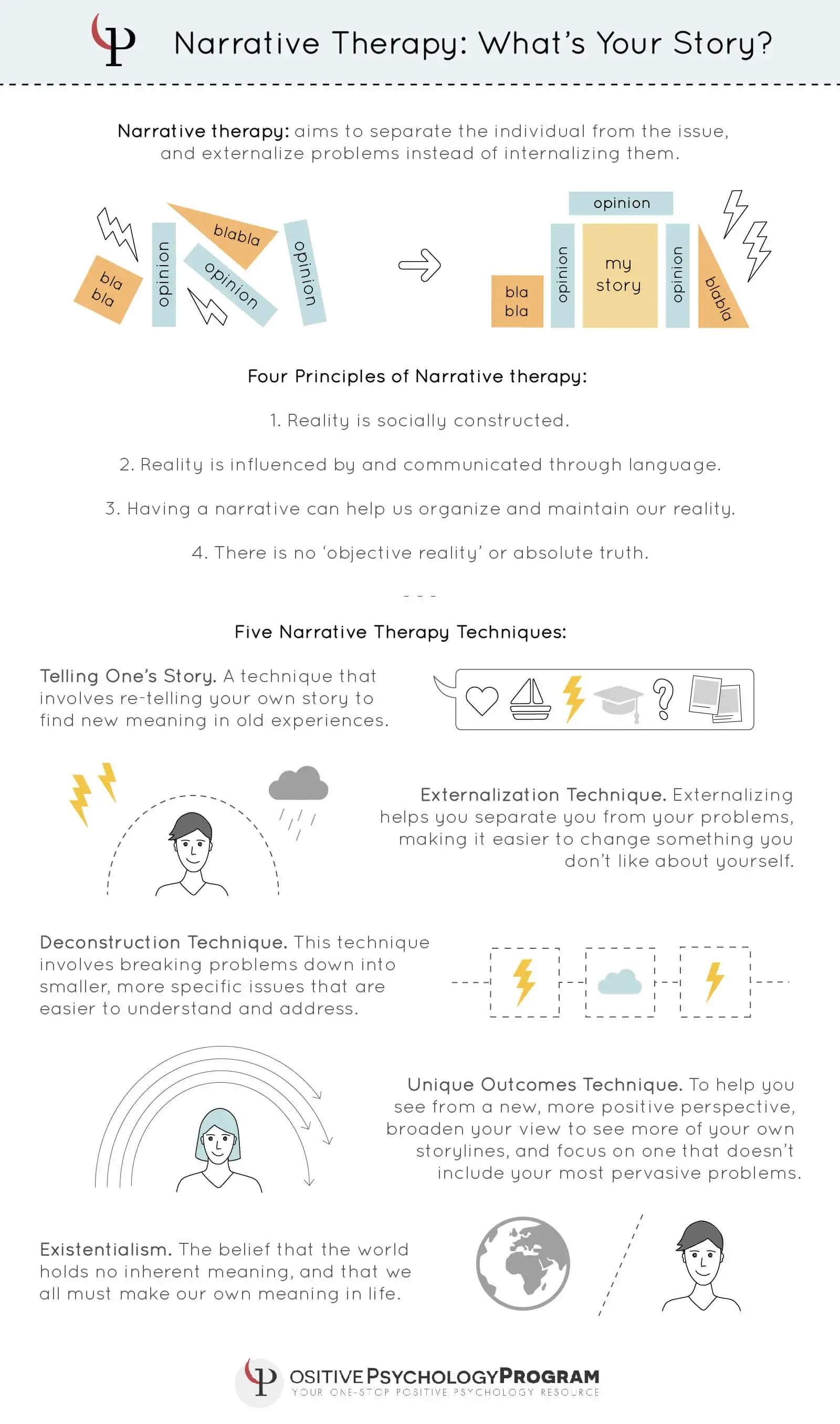

To this end, there are a few main themes or principles of narrative therapy:

- Reality is socially constructed, which means that our interactions and dialogue with others impacts the way we experience reality.

- Reality is influenced by and communicated through language, which suggests that people who speak different languages may have radically different interpretations of the same experiences.

- Having a narrative that can be understood helps us organize and maintain our reality. In other words, stories and narratives help us to make sense of our experiences.

- There is no “objective reality” or absolute truth; what is true for us may not be the same for another person, or even for ourselves at another point in time (Standish, 2013).

These principles tie into the postmodernist school of thought, which views reality as a shifting, changing, and deeply personal concept. In postmodernism, there is no objective truth—the truth is what each one of us makes it, influenced by social norms and ideas.

Unlike modern thought that held the following tenets as sacred, postmodern thought holds skepticism over grand narratives, the individual, the idea of neutral language, and universal truth.

Thus, the main premise behind narrative therapy is understanding individuals within this postmodern context. If there is no universal truth, then people need to create truths that help them construct a reality that serves themselves and others. Narrative therapy offers those story-shaping skills.

It’s amazing how much easier solving or negating a problem can be, when you stop seeing the problem as an integral part of who you are, and instead, as simply a problem.

5 Commonly Used Narrative Therapy Techniques

The five techniques here are the most common tools used in narrative therapy.

1. Telling One’s Story (Putting Together a Narrative)

As a therapist or other mental health professional, your job in narrative therapy is to help your client find their voice and tell their story in their own words. According to the philosophy behind narrative therapy, storytelling is how we make meaning and find purpose in our own experience (Standish, 2013).

Helping your client develop their story gives them an opportunity to discover meaning, find healing, and establish or re-establish an identity, all integral factors for success in therapy.

This technique is also known as “re-authoring” or “re-storying,” as clients explore their experiences to find alterations to their story or make a whole new one. The same events can tell a hundred different stories since we all interpret experiences differently and find different senses of meaning (Dulwich Centre, n.d.).

2. Externalization Technique

The externalization technique leads your client toward viewing their problems or behaviors as external, instead of an unchangeable part of themselves. This is a technique that is easier to describe than to embrace, but it can have huge positive impacts on self-identity and confidence.

The general idea of this technique is that it is easier to change a behavior you do, than to change a core personality characteristic.

For example, if you are quick to anger or you consider yourself an angry person, then you must fundamentally change something about yourself to address the problem; however, if you are a person who acts aggressively and angers easily, then you need to alter the situations and behaviors surrounding the problem.

It might seem like an insignificant distinction, but there is a profound difference between the mindset of someone who labels themselves as a “problem” person and someone who engages in problematic behavior.

It may be challenging for the client to absorb this strange idea at first. One first step is to encourage your client not to place too much importance on their diagnosis or self-assigned labels. Let them know how empowering it can be to separate themselves from their problems, and allowing themselves a greater degree of control in their identity (Bishop, 2011).

3. Deconstruction Technique

Our problems can feel overwhelming, confusing, or unsolvable, but they are never truly unsolvable (Bishop, 2011).

Deconstructing makes the issue more specific and reduces overgeneralizing; it also clarifies what the core issue or issues actually are.

As an example of the deconstruction technique, imagine two people in a long-term relationship who are having trouble. One partner is feeling frustrated with a partner who never shares her feelings, thoughts, or ideas with him. Based on this short description, there is no clear idea of what the problem is, let alone what the solution might be.

A therapist might deconstruct the problem with this client by asking them to be more specific about what is bothering them, rather than accepting a statement such as, “my spouse doesn’t get me anymore.”

This might lead to a better idea of what is troubling the client, such as general themes of feeling lonely or missing romantic intimacy. Maybe the client has construed a narrative where they are the victim of this helpless relationship, rather than someone with a problem coping with loneliness and communicating this vulnerability with their partner.

Deconstructing the problem helps people understand what the root of problems (in this case, someone is feeling lonely and vulnerable) and what this means to them (in this case, like their partner doesn’t want them anymore or is not willing to commit to the relationship like they are).

This technique is an excellent way to help the client dig into the problem and understand the foundation of the stressful event or pattern in their life.

4. Unique Outcomes Technique

This technique is complex but vital for the storytelling aspect of narrative therapy.

The unique outcomes technique involves changing one’s own storyline. In narrative therapy, the client aims to construct a storyline to their experiences that offers meaning, or gives them a positive and functional identity. This is not as misguided as “thinking positive,” but rather, a specific technique for clients to develop life-affirming stories.

We are not limited to just one storyline, though. There are many potential storylines we can subscribe to, some more helpful than others.

Like a book that switches viewpoints from one character to another, our life has multiple threads of narrative with different perspectives, areas of focus, and points of interest. The unique outcomes technique focuses on a different storyline or storylines than the one holding the source of your problems.

Using this technique might sound like avoiding the problem, but it’s actually just reimagining the problem. What seems like a problem or issue from one perspective can be nothing but an unassuming or insignificant detail in another

(Bishop, 2011).

As a therapist, you can introduce this technique by encouraging client(s) to pursue new storylines.

5. Existentialism

You might have a particular association with the term “existentialism” that makes its presence here seem odd, but there is likely more to existentialism than you think.

Existentialism is not a bleak and hopeless view on a world without meaning.

In general, existentialists believe in a world with no inherent meaning; if there is no given meaning, then people can create their own meaning. In this way, existentialism and narrative therapy go hand in hand. Narrative therapy encourages individuals to find their meaning and purpose rather than search for an absolute truth that does not necessarily resonate for themselves.

If your client is an avid reader, you might consider suggesting some existentialist works as well, such as those by Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, or Martin Heidegger.

The visual below helps summarize what narrative therapy is, and how it can be used.

You can download the printable version of the infographic here.

3 More Narrative Therapy Exercises and Interventions

While narrative therapy is more of a dialogue between the therapist and client, there are some exercises and activities to supplement the regular therapy sessions. A few of these are described below.

1. Statement of Position Map

- Characteristics and naming or labeling of the problem

- Mapping the effects of the problem throughout each domain of life it touches (home, work, school, relationships, etc.)

- Evaluation of the effects of the problem in these domains

- Values that come up when thinking about why these effects are undesirable

This map is intended to be filled out in concert with a therapist, but it can be explored if it is difficult to find a narrative therapist.

Generally, the dialogue between a therapist and client will delve into these four areas. The therapist can ask questions and probe for deeper inquiry, while the client discusses the problem they are having and seeks insight in any of the four main areas listed above. There is power in the act of naming the problem and slowly shifting the idea that we are a passive viewer of our lives.

Finally, it is vital for the client to understand why this problem bothers them on a deeper level. What values are being infringed upon or obstructed by this problem? Why does the client feel negative about the problem? For example, what does the “stressful dinner party” bring up for them? Perhaps feelings of social anxiety and “otherness” that feel isolating? These are questions that this exercise can help to answer.

For a much more comprehensive look at this exercise, you can read these workshop notes from Michael White on using the statement position maps.

You can also access a PowerPoint in which a similar exercise is covered here.

2. My Life Story

This exercise is all about your story, and all you need is the printout and a pen or pencil.

The intention of the My Life Story exercise is to separate yourself from your past and gain a broader perspective on your life. It aims to create an outline of your life that does not revolve too intensly around memories as much as moments of intensity or growth.

First, you write the title of the book that is your life. Maybe it is simply “Monica’s Life Story,” or something more reflective of the themes you see in your life, like “Monica: A Story of Perseverance.”

In the next section, come up with at least seven chapter titles, each one representing a significant stage or event in your life. Once you have the chapter title, come up with one sentence that sums up the chapter. For example, your chapter title could be “Awkward and Uncertain” and the description may read “My teenage years were dominated by a sense of uncertainty and confusion in a family of seven.”

Next, you will consider your final chapter and add a description of your life in the future. What will you do in the future? Where will you go, and who will you be? This is where you get to flex your predictive muscles.

Finally, the last step is to add to your chapters as necessary to put together a comprehensive story of your life.

This exercise will help you to organize your thoughts and beliefs about your life and weave together a story that makes sense to you. The idea is not to get too deep into any specific memories, but instead to recognize that what is in your past is truly the past. It shaped you, but it does not have to define you. Your past made you the reflective and wiser person of today.

You can download this worksheet here.

3. Expressive Arts

This intervention can be especially useful for children, but adults may find relief and meaning in it as well.

We all have different methods of telling our stories, and using the arts to do so has been a staple of humanity for countless generations. To take advantage of this expressive and creative way to tell your stories, explore the different methods at your disposal.

You can:

- Meditate. Guided relaxation or individual meditation can be an effective way to explore a problem.

- Journal. Journaling has many potential benefits. Consider a specific set of question s (e.g., How does the problem affect you? How did the problem take hold in your life?) or simply write a description of yourself or your story from the point of view of the problem. This can be difficult but can lead to a greater understanding of the problem and how it influences the domains of your life.

- Draw. If you’re more interested in depictions of the problem’s impact on your experience, you can use your skills to draw or paint the effects of the problem. You can create a symbolic drawing, map the effects of the problem, or create a cartoon that represents the problem in your life. If drawing sounds intimidating, you can even doodle abstract shapes with the colors of the emotions you feel, and keywords that express your reflection in that moment.

- Movement. You can use the simple medium of movement and mindfulness to create and express your story. Begin by moving in your usual way, then allow the problem to influence your movement. Practice mindful observation to see what changes when you let the problem take hold. Next, develop a transitional movement that begins to shake the problem’s hold on you. Finally, transition into a “liberation movement” to metaphorically and physically explore how to escape the problem.

- Visualization. Use visualization techniques to consider how your life might be in a week, a month, a year, or a few years, both with this problem continuing and in a timeline where you embrace a new direction. Share your experience with a partner or therapist, or reflect in your journal to explore the ways in which this exercise helped you find meaning or new possibilities for your life (Freeman, 2013).

If you’re interested in learning more about how to put your creativity to work on developing a more positive story, follow this link or click here to dive a little deeper into expressive arts therapy.

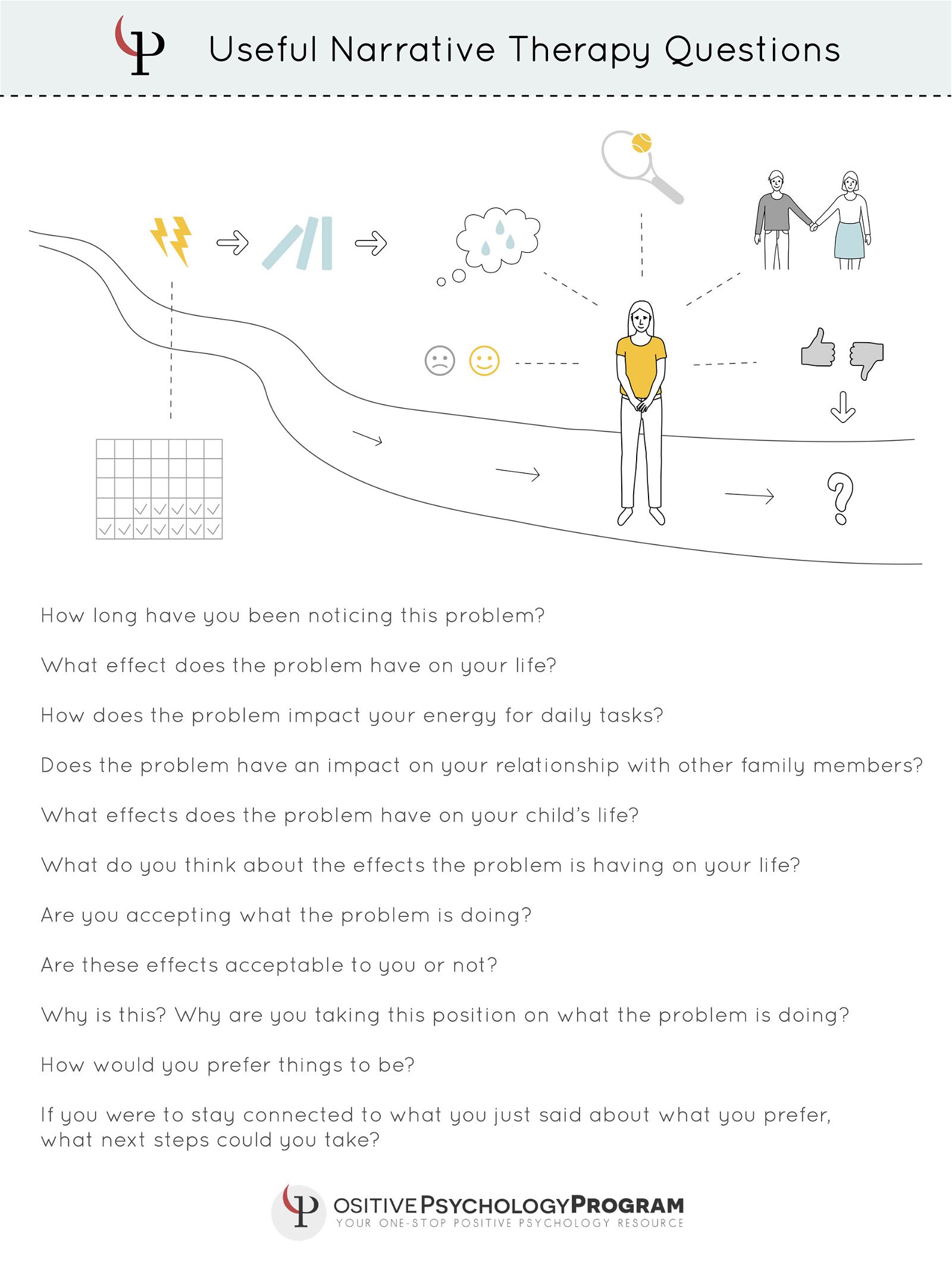

Examples of Questions to Ask Your Clients

Narrative therapy is a dialogue in which both you and your client converse to learn about your story. As you may imagine, it requires many questions on the part of the therapist.

“Every time we ask a question, we’re generating a possible version of a life.”

David Epston

The list of questions below is intended to go with the statement of position maps, but these questions can be useful outside of this exercise too:

- It sounds as though [problem] is part of your life now.

- How long have you been noticing this [problem]?

- What effect does the [problem] have on your life?

- How does the [problem] impact on your energy for daily tasks?

- Does [problem] have an impact on your relationship with other family members?

- What effects does [problem] have on your child’s life?

- What do you think about the effects [problem] is having on your life?

- Are you accepting what [problem] is doing?

- Are these effects acceptable to you or not?

- Why is this? Why are you taking this position on what [problem] is doing?

- How would you prefer things to be?

- If you were to stay connected to what you have just said about what you prefer, what next steps could you take?

The website www.integratedfamilytherapy.com also provides excellent examples of questions to ask your client as you move through their story:

- Enabling Openings

Can you describe the last time you managed to get free of the problem for a couple of minutes? What was the first thing you noticed in those few minutes? What was the next thing? - Linking Openings with Preferred Experience

Would you like more minutes like these in your life? - Moving from Openings to Alternative Story Development.

What was each of you thinking/feeling/doing/wishing/imagining during those few minutes? - Broadening the Viewpoint.

What might your friend have noticed about you if she had met up with you in those few minutes? - Exploring Landscapes of Action.

How did you achieve that? How did Tim help you with that? - Exploring Landscapes of Consciousness.

What have you learned about what you can manage from those few minutes? - Linking with the Exceptions in the Past.

Tell me about times when you have managed to achieve a similar few minutes in the past? - Linking Exceptions from the Past with the Present.

When you think about those times in the past when you have achieved this, how might this alter your view of the problem now? - Linking Exceptions from the Past with the Future.Thinking about this now, what do you expect to do next?

You can download the printable version of the infographic here.

Narrative Therapy Treatment Plan

Developing a treatment plan for narrative therapy is a personal and intensive activity in any therapeutic relationship, and there are guidelines for how to incorporate an effective plan.

This PDF provides a profile of a treatment plan, including goals and guidelines for each stage and theories that can apply to the client’s treatment.

The co-founder of narrative therapy, Michael White, offers an additional resource for therapists using narrative therapy.

According to White, there are three main processes in treatment:

1) Externalization of the problem, which mirrors the steps of the position mapping exercise:

- Developing a particular, experience-near definition of the problem;

- Mapping the effects of the problem;

- Evaluating the effects of the problem;

- and justifying the evaluation.

2) Re-authoring conversations by:

- Helping the client include neglected aspects of themselves;

- and shifting the problem-centered narrative.

3) Remembering conversations that actively engage the client in the process of:

- Renewing their relationships;

- Removing the relationships that no longer serve them;

- and finding meaning in their story that is no longer problem-saturated as much as resilient-rich.

Best Books on Narrative Therapy

If you’re as much of a bookworm as I am, you’ll want a list of suggested reading to complement this piece. You’re in luck!

These three books are some of the highest rated books on narrative therapy and offer a solid foundation in the practice of narrative techniques.

1. Maps of Narrative Practice – Michael White

This book from one of the developers of narrative therapy takes the reader through the five main areas of narrative therapy, according to White: re-authoring conversations, remembering conversations, scaffolding conversations, definitional ceremony, and externalizing conversations.

In addition, the book maps out the therapeutic process, complete with implications for treatment and skills training exercises for the reader.

Find the book on Amazon.

2. What is narrative therapy?: An easy-to-read introduction – Alice Morgan

This best-seller provides a simple and easy to understand introduction to the main tenets of narrative therapy.

In this book, you will find information on externalization, remembering, therapeutic letter writing, journaling, and reflection in the context of narrative therapy.

Morgan’s book is especially useful for therapists and other mental health professionals who wish to add narrative techniques and exercises to their practice.

Find the book on Amazon.

3. Narrative Therapy: The Social Construction of Preferred Realities – Gene Combs and Jill Freedman

This book is best saved for those who want to dive headfirst into the philosophical underpinnings of narrative therapy.

Casual readers interested in learning more about narrative therapy may want to try one of the first two books; students, teachers, and practitioners will find this book challenging, informative, and invaluable to their studies.

Included in this book are example transcripts and descriptions of therapy sessions in which the principles and interventions of narrative therapy are applied.

Find the book on Amazon.

YouTube Videos for Further Exploration

1. This quick, 5-minute video can give you an idea of how some of the techniques of narrative therapy can be applied in real counseling sessions, specifically with children and families. As Dr. Madigan quotes in this video, “we speak ourselves into meaning.”

We need to speak in ways that serve us.

3. Finally, for a fun and engaging exploration of narrative therapy for in couples counseling, click the link below. It leads to a video involving puppets and outlining some of the main techniques and principles involved in narrative couples therapy.

Around four minutes in, a breakthrough moment occurs when the therapist puppet says, “so you’re feeling anxious because you don’t know what direction this is going to take you.” This is an example of deconstructive questioning, and how it helps uncover the deeper vulnerability of any “problem.”

A Handy PowerPoint to Use

If you’re more a reader or if you like to go at your own pace, check out this slideshow on narrative therapy.

It’s intended for students learning about narrative therapy in an academic setting. Some of the languages may seem specific and jargon abounds, but there is some great information in here for any readers curious about the philosophy, principles, and theories behind narrative therapy.

Follow this link to view the slideshow.

A Take-Home Message

How do you tell your story? What are the chapters of your life? Do you like the story you tell, or would you prefer to change your story? These and many other questions can be answered in narrative therapy.

“There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

Maya Angelou

If you’re an individual curious about narrative therapy, I hope your curiosity is piqued and that you have a foundation now for further learning.

If you’re a therapist or other mental health professional interested in applying narrative therapy in your work, I hope this piece can give you a starting point for you.

As always, please leave us your thoughts in the comment section. Have you tried narrative therapy? If so, what did you think? Did you find it useful? What techniques in particular capture your interest?

Thanks for reading and happy storytelling!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- About Narrative Therapy. (n.d.). Narrative Therapy Centre of Toronto. Retrieved from http://www.narrativetherapycentre.com/narrative.html

- Bishop, W. H. (2011, May 16). Narrative therapy summary. Thoughts From a Therapist. Retrieved from http://www.thoughtsfromatherapist.com/2011/05/16/narrative-therapy-summary/

- Dulwich Centre. (n.d.). What is narrative therapy? Dulwich Centre. Retrieved from http://dulwichcentre.com.au/what-is-narrative-therapy/

- Freeman, J. (2013, June 5). Expressive arts workshop materials. Narrative Approaches. Retrieved from http://www.narrativeapproaches.com/expressive-arts-workshop-materials/

- Michael White (1948-2008). (2015, July 24). GoodTherapy. Retrieved from http://www.goodtherapy.org/famous-psychologists/michael-white.html

- Morgan, A. (2000). What is narrative therapy? An easy-to-read introduction. Adelaide, SA: Dulwich Centre Publications.

- Narrative Therapy. (2017). Good Therapy. Retrieved from http://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/narrative-therapy

- Standish, K. (2013, November 28). Introduction to narrative therapy [Slideshow]. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/kevins299/lecture-8-narrative-therapy

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (54)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (39)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (44)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (13)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (41)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (13)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)

What our readers think

I always enjoy relearning the techniques of Narrative Therapy but could use a guideline that focuses on Addiction. I am a co-occurring therapist that works with Addiction and Mental Health and use externalization a lot. It would be great if you had a specific worksheet/questionnaire that addresses addiction specifically.

Thanks so much for your insight!

Kind Regards,

Diane Music

Dear Diane,

Thank you for reaching out and expressing your interest in resources specifically designed for the context of addiction. It’s wonderful to hear you’re applying Narrative Therapy techniques in your work!

Although we presently lack resources specifically tailored to your case, we recommend adapting the principles of Narrative Therapy to suit the unique needs of your clients battling addiction:

– Externalizing the Problem: As you’re already doing, this can be particularly beneficial in addiction therapy. It helps the client see their addiction as a separate entity rather than an inherent part of themselves. They can then examine how ‘the addiction’ influences their life and choices.

– Deconstructing Dominant Narratives: Encourage clients to explore societal and personal beliefs about addiction. Challenge these narratives and help clients construct their own, empowering narratives.

– Highlighting Unique Outcomes: Help your clients identify times when they successfully resisted the ‘pull’ of addiction. These ‘unique outcomes’ can help them see their own strength and capacity for change.

– Letter Writing: This can be a powerful tool for clients to communicate with their ‘addiction,’ express their feelings, or articulate their hopes for the future.

– Mapping the Influence: Create a visual map of how addiction influences different areas of their life. This can be a powerful tool for externalization and for identifying areas to work on.

We hope to have more specialized resources available soon. Until then, we believe the techniques mentioned above, when applied with sensitivity and creativity, can be highly effective in a narrative approach to addiction therapy.

Thank you for the impactful work you’re doing!

Best Regards,

Julia | Community Manager

“Expressive Arts. This intervention can be especially useful for children, but adults may find relief and meaning in it as well.”

As an expressive arts therapist, I found this comment to be confusing and somewhat misinformed. Firstly, the “expressive arts” are not an intervention, but are a collective of psychotherapeutic techniques and disciplines. There is also an insinuation that the expressive arts (or, more accurately, “expressive arts therapy”) are mostly for children, while adults, secondarily, “may find relief and meaning in it as well.” I have worked primarily with adults as an expressive therapist. The misconception that expressive therapy is mostly for children is a bias that many of us must contend with from those who do not understand that we are trained psychotherapists who work with adults. Thank you.