Positive Deviance: 5 Examples Of The Power of Non-Conformity

Like all other forms of life on earth, humans are the sum of countless random inherited mutations.

Like all other forms of life on earth, humans are the sum of countless random inherited mutations.

Over hundreds of thousands of years, selected genetic deviations have led to positive adaptations, increasing our ancestors’ chance of survival and having offspring, and being passed on to later generations.

Useful adaptations ultimately become part of what is normal; others, providing no benefit, are lost.

And yet, in society, even positive deviance is often seen as a violation of cultural rules and met with disapproval and fear (Goode, 1991).

However, research has shown that the departure from expected behavior can have incredible, far-reaching, and positive effects. Outliers often succeed against all the odds, figuring out problems that others are unable to solve.

This article reviews the interdisciplinary concept of positive deviance and its potential to help solve humanity’s biggest problems. We find examples of behavior where failure to conform led to unique solutions to problems at a societal level that no one else could fathom.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify opportunities for professional growth and create a more meaningful career.

This Article Contains:

Positive Deviance Defined

In the early 1990s, Jerry Sternin was the director of the Save the Children program in Vietnam, and he had a big problem.

His job was to find a way to feed impoverished villagers and their malnourished children, but his funding had been cut. Plans to bring in food, experts, and new agriculture techniques flew out the window (Pascale, Sternin, & Sternin, 2010).

Nevertheless, what he did next was a game-changer.

With no money to throw at the problem, the team enlisted locals’ help, asking them one simple question:

Who among them had the best-fed children?

What they were asking amounted to who in the village broke from convention and were able to feed their children while others were starving.

The answers confirmed that there were families with well-fed children; their mothers breaking existing customs by:

- Feeding their children even when they had diarrhea

- Giving them multiple smaller meals rather than two big ones

- Adding ‘leftover’ sweet potato greens to meals. Though loaded with micronutrients, they were traditionally thought unsuitable for young children and thrown away

- Collecting small shrimp and crabs found in the paddy fields – rich in protein and minerals – and including them in their family’s diet

- Avoiding food waste by actively feeding their children rather than setting the food down in front of them

Within two years of rolling out the lessons learned to other communities, malnutrition had dropped between 65% and 85%. The results were even better than what was expected if the original funding had been available (Pascale et al., 2010).

As Sternin observed, positive deviants are in the same situation as the rest of us, and yet, against all the odds, they succeed. Individual differences that lead to a positive impact should be recognized and celebrated. This approach, as with positive psychology, focuses on strengths rather than weaknesses.

The advantage of using positive deviants from within the target group is that they often have the same information but they use it differently, in a way that outsiders would fail to see.

This approach, according to Richard Pascale et al. (2010), is particularly useful when the problem:

- Forms part of a complex social system

- Calls for both social and behavioral change

- Entails solutions where the outcome may be uncertain and unpredictable

Positive deviance is more of an approach than a model, and, as such, it is highly flexible and can be tailored to the situation.

In 2001, following successes in Vietnam and beyond, Sternin received a grant from the Ford Foundation and helped found the Positive Deviance Initiative. Their mission statement reads as follows:

Promoting Social Change From the Inside Out, Leveraging Local Wisdom for Global Impact

Theory and Research Behind The Concept

But focus on standard practices (the mediocre) appears to have led to the failure of many intervention strategies and, as such, may not be the best approach for change.

Looking back, deviant human behavior has been the subject of study since the early 1900s and has provided considerable insight into ‘normal’ and ‘marginal’ human social nature.

Early research explored unpleasant and offensive behavior before recognizing the lessons to be learned from the edges of human conduct in maintaining balance in the social order (Spreitzer & Sonenshein, 2004).

While intuitively, positive deviance is easy to recognize and understand, a practical definition applicable to all situations appears elusive.

However, over the years, several attempts have been made to capture its essence.

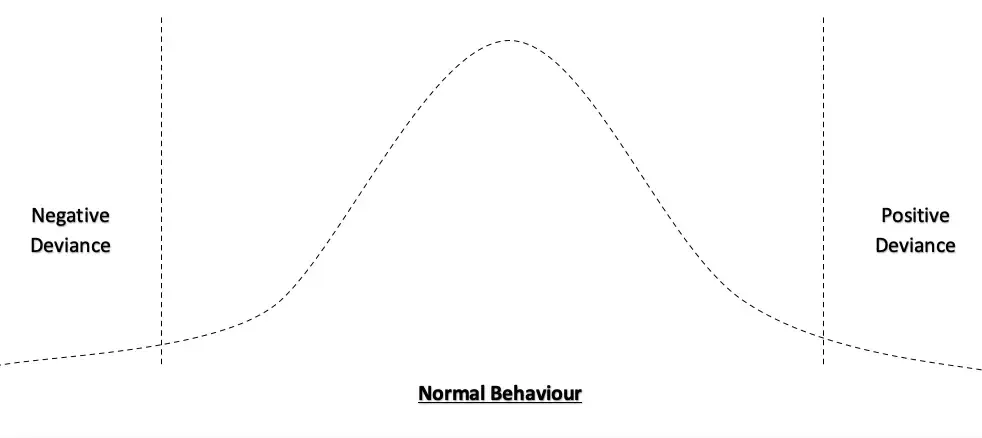

The statistical approach searches for behavior that differs from the majority. Action, when expressed as a bell curve, identifies deviant individuals at the extremes of normal distribution, as represented below (modified from Spreitzer & Sonenshein, 2004):

According to Robert Quinn (1996), such individuals – exemplified by world-class athletes or top-performing managers – stand out from the rest.

Another definition of positive deviance, known as the reactive approach, acknowledges the majority’s reaction to the few’s unusual behavior. If the response is not adverse, then the practice is not positively deviant (Dodge, 1985).

The normative approach, favored by Gretchen Spreitzer and Scott Sonenshein, regards positive deviance as a “departure from the norm.” Athletes are no longer identified as positive deviants as their behavior is based on performance rather than breaking from cultural normality.

In a 2017 review, Matthew Herington and Elske van de Fliert describe positive deviance as an “attractive concept to aid in understanding the nature of and potential solutions for complex social problems.” Their findings, based on a systematic review of existing literature, recognize positive deviation as necessary to a functioning society, affirming cultural boundaries and societal norms.

Recent research focuses less on finding a definition and more on applying the approach to complex problems including childhood obesity, hygiene, health in slums, and gender empowerment.

The Steps of Positive Deviance

Positive deviance is perhaps better thought of as a positive mindset rather than a model or theory. Its strengths are its simplicity, widespread applicability, and brevity.

The approach is ideal for facing an intractable problem requiring a solution that includes social and behavioral change.

The four Ds – define, determine, discover, and design – are central to delivering a positive deviance outcome (Pascale et al., 2010):

Step 1 – Define the problem and the necessary outcome

The community itself (rather than a set of outsiders) defines, refines, and reframes the issue.

Actions:

- Engage with the community to understand the data that measures the problem.

- Create a view of how an improved or ideal future would look.

- Explore the issues and barriers associated with the problem.

- Identify the stakeholders.

- Be open, and share the findings in community forums.

Step 2 – Determine common practices

The community is most qualified to determine commonplace practices and behaviors.

Actions:

- Set up meetings to include different groups across the community.

- Involve the community in identifying activities, learnings, and prioritization.

Step 3 – Discover uncommon, successful behaviors

The community identifies positive deviants.

Actions:

- Identify who in the community faces the same challenges, with the same resources, yet tackles the problem successfully.

- Interview individuals displaying deviant behavior.

- Identify the uncommon practices that lead to improved outcomes.

- Share the lessons learned with the community.

Step 4 – Design an initiative using the learnings

The community comes up with the design and the activities to expand the reach of the solution.

Actions:

- Apply the learned positive deviance behaviors.

- Begin small, then expand the roll-out.

- Connect people who were not previously connected.

- Create opportunities for learning to take place.

The community itself will monitor the overall effectiveness of the initiative.

If successful, document the insights gained and suggested behavior, and share beyond the original community to others facing similar challenges.

4 Real-Life Examples of Positive Deviance

The following is a small sample of cases that exemplify positive deviance. Each covers a very different context and highlights its power to address a wide range of issues.

The rise and fall of the encyclopedia

The days of flicking through hefty, leather-bound volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica to find the answer to a question have long since passed.

Today, we type a phrase into our computers, tablets, or phones, and Wikipedia undoubtedly provides us with the answer.

Incredibly, this free online encyclopedia (over 54 million articles in hundreds of languages) is written not by a centralized group of writers and editors, but by individuals like you and me. Ordinary people who have exceptional knowledge or a close connection with a specific topic write an article, and others review and update it.

The old centralized way of writing, storing, and retrieving knowledge is dead, replaced by a decentralized, digital, searchable, evolving body of information that is growing daily and never static (Singhal et al., 2013).

Alan Turing, the brilliant misfit

Alan Turing was a mathematical genius who, during the Second World War, played a pivotal role in breaking enemy codes. Indeed, it is widely accepted that Alan Turing’s brilliance played a significant part in shortening the Second World War’s duration by several years (Turing, 2020).

Much of code breaking involved tediously, manually solving encrypted codes from intercepted transmissions. Turing broke rank and, along with fellow codebreaker Gordon Welchman, created an electronic device known as the Bombe to automate the work.

In turn, Turing provided much of the original thinking needed to solve the previously unbreakable Enigma code used by German military forces. His strength was his ability to decipher intricate patterns and tackle the problem of code breaking itself.

Alongside his cryptography expertise, his work on a hypothetical computer, beginning in 1936, led him to be called the founding father of computer science and artificial intelligence.

Tackling the male ego

A health initiative to promote smaller family sizes in New Delhi found that men often failed to turn up for their vasectomy. As a result of the no-shows, the remaining men would often leave and not return.

Using a less traditional, positive deviance influenced approach, the team reengineered the setup.

They requested that the more motivated vasectomy seekers stride to the front and demand to be seen first. Then, after the operation, the willing volunteers were asked to boast of the procedure’s painlessness as they left.

The positive role models – rejecting the waiting men’s preconceptions and ‘proving’ the operation’s positive nature – directly led to an increase in vasectomy completion rates (Singhal et al., 2013).

While an unlikely setting, the vasectomy clinic proved the value of seeking out the exceptional – the positive deviants – and sharing their beliefs (albeit mildly duplicitous ones) to a more significant effect.

Managing diabetes

A public health initiative in Epsom, New Hampshire, partnered with patients who were highly successful in managing type 2 diabetes.

The project, led by Dr. Zanetti, exemplified the positive deviance approach (Zanetti & Taylor, 2016). They first identified and recruited patients who had found creative means to manage their medication and diet, build their motivation and a sense of purpose, and adopt a healthy coping mechanism with support from their partners.

Intervention nights called Diabetes Dinner Club and Discussion were then arranged, where the positive deviants, known as “bright spotters,” passed on their knowledge to those less equipped to handle the disease (Selby, 2015; Zanetti & Taylor, 2016).

What is positive deviance? – HealthyGamerGG

Applications of Positive Deviance

The positive deviance approach tackles challenges in healthcare settings head on by looking for exceptional professionals and patients (Zanetti & Taylor, 2016).

Their actions are recognized as deviant.

And, as we have already seen, its use in public health initiatives has been highly successful in multiple areas, overcoming many of the issues faced by other programs, including limited money, resources, training, and equipment.

Successful interventions include (Zanetti & Taylor, 2016; Singhal et al., 2013; Pascale et al., 2010):

- Childhood malnutrition in Vietnam

- Hospital-acquired infections

- Female circumcision in Egypt

- Management of type 2 diabetes

- Cystic fibrosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Hypertension

- Immunization

- Cancer care

However, the benefits of positive deviance are not restricted to healthcare interventions.

Success has also been found in the following contexts (Hoffman & Haigh, 2010; Setiawan & Sadiq, 2013; Neville, 2008; Herington & van de Fliert, 2017):

- Sustainable development

- Ethical business growth

- Business process improvement

- Management and leadership

- Criminology

- Psychology

- International development

- Arts and music

- Computer science

Despite its origins in sociology, positive deviance has incredible potential as a tool or framework for practical application in many other areas, helping to understand successful departures from the norm and “effecting positive social change” (Herington & van de Fliert, 2017).

6 Books on the Topic

However, the first one in our list is an excellent resource – well written, entertaining, and providing food for thought – and offers the most in-depth explanation, along with anecdotal evidence, of the strengths of the approach.

- The Power of Positive Deviance: How Unlikely Innovators Solve the World’s Toughest Problems – Richard Pascale, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin (Amazon)

The following books provide related content, offering insights into the importance of exceptional and alternative behavior:

- Outliers: The Story of Success – Malcolm Gladwell (Amazon)

- David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants – Malcolm Gladwell (Amazon)

- Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard – Chip Heath (Amazon)

- The Future of Management – Gary Hamel (Amazon)

- The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success – William Thorndike (Amazon)

A Take-Home Message

The world is facing ever-increasing challenges, some at a local level and others requiring international cooperation.

We need novel solutions to tackle the enormity of these problems using the resources we have.

This is when we should turn our attention to those who do not fit the norm, people who think differently and overcome problems in an unexpected way.

Instead of condemning behavior that is at odds with our customs and cultural norms, we need to identify and “work with the few, the exceptional, the positive deviants” (Singhal et al., 2013).

And rather than focusing on normal behavior that extends the problem, we must identify and understand what actions are proving successful, potentially against all the odds, using the resources we share.

Like positive psychology, positive deviance focuses on what is right rather than what is wrong.

If we are to address humanity’s greatest threats – overpopulation, famine, poverty, climate change, loss of jobs due to automation, pandemics, and mental health problems – we need to search for those pockets of people, the positive deviants, who are doing things right.

We must understand them, learn what they do well, and share their knowledge beyond their community.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free.

- Dodge, D. (1985). The over-negativized conceptualization of deviance: A programmatic exploration. Deviant Behavior, 6(1), 17–37.

- Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Little, Brown.

- Gladwell, M. (2013). David and Goliath: Underdogs, misfits and the art of battling giants. Allen Lane.

- Goode, E. (1991). Positive deviance: A viable concept? Deviant Behavior, 12(3), 289–309.

- Hamel, G., & Breen, B. (2007). The future of management. Harvard Business Press.

- Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2010). Switch: How to change things when change is hard. Crown Business.

- Herington, M. J., & van de Fliert, E. (2017). Positive deviance in theory and practice: A conceptual review. Deviant Behavior, 39(5), 664–678.

- Hoffman, A. J., & Haigh, N. (2010). Positive deviance for a sustainable world: Linking sustainability and positive organizational scholarship. In K. S. Cameron & G. M. Spreitzer (Eds.) The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Neville, M. G. (2008). Positive deviance on the ethical continuum: Green Mountain Coffee as a case study in conscientious capitalism. Business and Society Review, 113(4), 555–576.

- Pascale, R., Sternin, J., & Sternin, M. (2010). The power of positive deviance: How unlikely innovators solve the world’s toughest problems. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Quinn, R. E. (1996). Deep change: Discovering the leader within. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Selby, L. (2015, October). Public health project taps into superstar patients’ expertise. Retrieved August 07, 2020, from https://thedo.osteopathic.org/2015/04/public-health-project-taps-into-superstar-patients-expertise/

- Setiawan, M. A., & Sadiq, S. (2013). A methodology for improving business process performance through positive deviance. International Journal of Information System Modeling and Design, 4(2), 1–22.

- Singhal, A., Shirley, S., & Holt Marston, E. (2013, June). The value of positive deviations. Retrieved August 7, 2020, from http://utminers.utep.edu/asinghal/Singhal_Value%20of%20Positive%20Deviations_2013_Development%20Magazine.pdf

- Spreitzer, G. M., & Sonenshein, S. (2004). Toward the construct definition of positive deviance. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 828–847.

- Thorndike, W. N. (2012). The outsiders: Eight unconventional CEOs and their radically rational blueprint for success. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Turing, S. J. (2020) Codebreakers of Bletchley Park: The secret intelligence station that helped defeat the Nazis. London, UK: Arcturus.

- Zanetti, C. A., & Taylor, N. (2016). Value co-creation in healthcare through positive deviance. Healthcare, 4(4), 277–281.

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (56)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (17)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (39)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (44)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (13)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (42)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (22)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)