What Is the Meaning of Life According to Positive Psychology

Throughout modern history, one of the questions that humans have asked the most is

Throughout modern history, one of the questions that humans have asked the most is

“What is the meaning of life?”

“Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible.”

Viktor Frankl

We are all hungry for meaning, for purpose, for the feeling that our life is worth more than the sum of its parts.

Luckily, humans are resourceful – we have infinite ways of finding meaning, and infinite potential sources of meaning. We can find meaning in every scenario, every event, every occurrence, every context. We can find meaning in the sublime, in the absurd, in the dull and dreary, and in the perfectly wretched in life.

We intuitively know that we want meaning in our lives, and that meaning helps us thrive, but we rarely stop to ask:

“Why do we need meaning? How does meaning affect us? What even IS meaning?”

If you have ever asked these questions yourself, you are in the right place! In this piece, we’ll go over what meaning is, where it may come from, how it can be found, and other important topics related to meaning in life.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free. These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations, and goals and will give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

7 Definitions of Meaning

First off, let’s make sure we are on the same page when we talk about meaning.

There are so many ways to define meaning that it’s impossible to narrow it down to just one or two “best” definitions of meaning. After all, “meaning” can have a different meaning for everyone!

Let’s start with the most basic definition for now.

We can get our trusty old dictionary (or, in this case, www.dictionary.com) out and flip over to the “M” section to get a no-nonsense definition of the word.

Meaning (noun):

- What is intended to be, or actually is, expressed or indicated; signification; import.

- The end, purpose, or significance of something.

Meaning (adjective):

- Intentioned.

- Full of significance; expressive

These definitions of meaning should be familiar to you. These are the definitions that apply when we say things like “What did he mean when he said that?” or “The meaning was lost on her.”

Of course, there are deeper levels to the meaning of “meaning.”

For example, www.vocabulary.com brings us a little deeper with the following definition:

“Meaning is what a word, action, or concept is all about – its purpose, significance, or definition. If you want to learn the meaning of the word meaning, you just need to look it up in the dictionary.”

Further, the website states:

“When you read a poem, you try to figure out the author’s intended meaning by interpreting the words he has chosen. For example, if a poet describes love as “a prison,” you might interpret the meaning as his feeling confined by his love.”

Now we’re getting to the real meat of the word – meaning is something we derive, something we share, and something we can create.

Moving on, not only are there different levels to the word, there are also different kinds of meanings. In linguistics, for example, there is both a semantic meaning, or the actual content, and a pragmatic meaning, or meaning that is dependent on context (Nordquist, 2017).

For example, the phrase “You put on quite a show!” has the same semantic meaning no matter what context it is uttered in, but the pragmatic meaning can vary widely.

Saying this to a child after seeing their performance in a school talent show would likely give it a very positive and complimentary pragmatic meaning, while saying it to a stranger who just slipped and fell on their way down the stairs would likely be received as neither positive nor complimentary.

In a more popular sense, meaning has been discussed as “a construct and experience shrouded in mystery” (Mattiuzzi, 2015), “what people try to create or find” (West, 2007), or simply replaced or substituted for words like “purpose” or “calling.”

Meaning can be described, defined, and considered in many different ways, and all of this happens even before we get to theories or philosophies on meaning! If you haven’t been scared off, read on to jump into the topic of meaning in philosophy.

Philosophizing Meaning

“Life has no meaning. Each of us has meaning and we bring it to life. It is a waste to be asking the question when you are the answer.”

Joseph Campbell

Many theories of meaning have been put forth over the last couple of centuries, as humans struggled to come to some kind of coherent understanding of what meaning is, how it is made, and how it can be found.

However, no theory has been proposed that answers all the big questions. Some answer one or two questions, while others might address another, but none of them offer a comprehensive view on the subject.

A few of the most significant theories of meaning are described below.

The meaning of life – The School of Life

Theories of Meaning

Although there are various theories of meaning, we discuss the following well-known theories:

Modernism

Generally, modernism is considered to be the reigning perspective on life and meaning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (“History of Modernism”, n.d.). It was a sharp departure from the mysticism and reliance on the supernatural that dominated the landscape previously, with its emphasis on “out with the old, in with the new!”

Modernists questioned the significance of traditions and, indeed, anything that we had gained or learned through traditional means. The innovation and staggering discoveries of the early 1900s thrust mankind into a world of new possibilities. Einstein’s theory of relativity only reinforced the idea that life and humanity were more nuanced than it had previously been considered.

Reason and logic replaced religion and superstition, and with these substitutions came a belief that the keys to a peaceful, utopian existence could be found in science rather than spirituality. Suddenly, meaning was no longer considered a default for humans, bestowed by an all-powerful creator; rather, it was something that could be discovered through logical deduction and reasoning.

Modernism spawned many new theories and perspectives that challenged the wisdom of tradition and conformity in favor of newer, more innovative ideas. One such offshoot was logical positivism.

Logical Positivism

This theory sorts sentences into one of three groups:

- Statements of fact, which can be verified.

- Analytical statements, which derive meaning from the words and structures that comprise them.

- Metaphysical, aesthetic, and ethical statements, which only appeal to emotion and contain no intellectual content (Holcombe, 2015).

Verification is a vital component of logical positivism. The idea that there are universal truths is one that underlies most modern scientific thinking, but logical positivism has a very different take on what counts as empirical proof – basically, all facts are verifiable by one’s senses alone.

This theory, although it quickly fell out of favor with the leading philosophers of the day, contributed to the search for a comprehensive theory of meaning through its emphasis on verifiable facts and the presence of at least some absolute truths. These factors carried over to many subsequent theories.

Postmodernism

On the other end of the spectrum, some theories held that meaning is not absolute or formed by empirical observation, but fluid and individual.

One such theory is postmodernism; this theory (or, more accurately, school of thought) rejected the idea of absolute truth or verifiable facts, believing instead that meaning can be discovered from a wide variety of places and from just about any source.

Postmodernists were suspicious of strict adherence to logic and disagreed that there was an objective reality irrespective of human beings. These philosophers hold that reality is created by humans, and that reason is simply one of many equally valid ways to discover one’s own truth (Duignan, n.d.).

Every human was free to discover her own unique meaning, and each human was the ultimate authority over her own reality.

Existentialism

Existentialism is a theory related to postmodernism, in that meaning is subjective and there is no universal code or moral authority.

However, it departs from postmodernism in its insistence that there is no inherent meaning; existentialism posits that each human creates his own meaning, rather than finding meaning in the world around him.

It may seem like a subtle difference, but it has some significant implications: existentialists question whether there is any natural order to things. Unlike modernists, existentialists do not see science and technology as the keys to a utopian society; instead, they believe that meaningful answers cannot be found in any single model of “being.”

They do not necessarily reject science or its findings, but they may see scientific theories as more like “descriptions” of the world than explanations or true understanding (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, n.d.).

In this school of thought, the idea that there could be an actual “meaning” to life is absurd. Humans are free to create meaning for themselves, but there is no inherent meaning in the universe they inhabit.

While all of these theories of meaning (or “being”) have contributed to our thinking about meaning, most modern conceptualizations of meaning differ significantly from each of them.

Current Research on Meaning

In modern psychology, meaning itself is generally no longer questioned; virtually all psychologists agree that meaning exists as a concept for humans, that it can be found in the world around us, and that we can create or uncover our own unique sense of meaning as well.

In that sense, we’ve come to a “post-postmodern” understanding of meaning. We are no longer seeing distinct, discrete theories of meaning; instead, we are comfortable mixing and mashing and merging ideas from different theories (Irvine, 2013). The current understanding of meaning, then, seems to be something like:

“We’re not sure exactly where meaning comes from, if it is inherent, or if it is ‘real’ at all; what we do know is that humans flourish when they have it and suffer when they don’t.”

This idea is prevalent in positive psychology in particular, where researchers theorize and experiment on how to increase meaning, the sources which provide meaning, and how we can manipulate our own experiences of meaning, all without diving too deep into the questions of where meaning comes from, in a broader sense, and whether it is inherent in life or not.

However, no area of study in psychology would be complete with competing theories and a plethora of opposing ideas. A few of the most popular and influential ideas on meaning in positive psychology are outlined below.

Frankl’s Meaning-Seeking Model

“Everything can be taken from a man but… the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

Viktor Frankl

While certainly not the most current, Viktor Frankl’s work on meaning laid the foundations for the research on meaning that occurred in the following decades.

Frankl developed his approach to meaning and his therapy for treating the lack of meaning before World War II, but refined it during his experience in Nazi concentration camps. His groundbreaking work on logotherapy and his experience in the camps is titled “Man’s Search for Meaning” for good reason – the main idea in his theory is that humans are driven by their desire for meaning.

Based upon this idea, Frankl developed three core components to his philosophy:

- Each individual has a healthy “core.”

- Each individual has the internal resources to “use” their healthy internal core.

- Life offers each individual purpose and meaning, but it does not owe anyone happiness or fulfillment (Good Therapy, 2015).

Further, Frankl proposed that meaning in life can be discovered in three ways:

- By creating a work or accomplishing some task.

- By experiencing something fully or loving somebody.

- By the attitude that one adopts toward unavoidable suffering (Good Therapy, 2015).

While suffering is an unavoidable part of life, Frankl encourages us to revel in our ability to choose how we respond to suffering. Indeed, experiencing suffering can actually compel us to find meaning that we would otherwise fail to see, depending on how we react to it.

Frankl’s work, while groundbreaking, did not delve as deep into the inner workings of meaning as some researchers want to go. Several researchers within and outside of positive psychology have their own take on meaning.

Meaning as Comprehension, Purpose, and Mattering

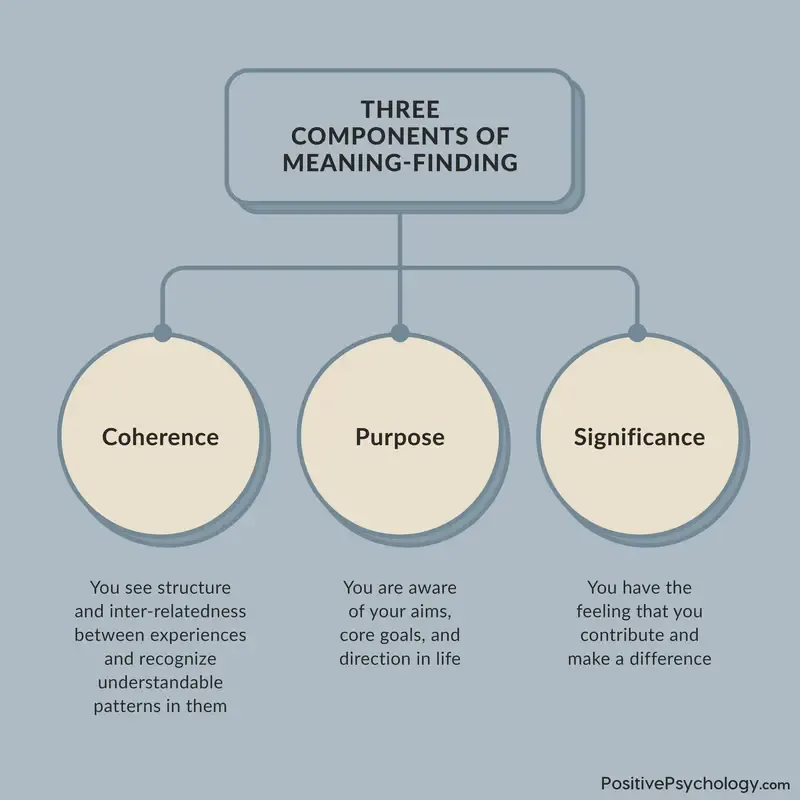

One such take on meaning comes from researchers George and Park. Their conceptualization of meaning in life considers it a three-part construct, defined as:

“[T]he extent to which one’s life is experienced as making sense, as being directed and motivated by valued goals, and as mattering in the world.”

This definition can be broken down into the three components:

- Comprehension, or the degree to which people perceive a sense of coherence and understanding regarding their own lives.

- Purpose, or the extent to which people experience life as being directed and motivated by valued life goals.

- Mattering, or the degree to which people feel their existence is significant, important, and of value to the world (George & Park, 2016).

Comprehension, purpose, and mattering should not be thought of as three distinct concepts, but as three closely related constructs that, together, make up meaning in life. They will naturally interact and influence one another; having a very low degree of one component will likely drag the others down, and vice versa.

These three components are also influenced by meaning frameworks or systems of thought about the way things are and the way things ought to be. If an individual finds that things are no longer making sense according to their systems of thought, these frameworks can be altered, scrapped, or replaced through the process of meaning maintenance, or meaning-making.

This three-component theory of meaning in life is still new, but it is a promising step towards a more comprehensive understanding of what meaning “means” for humans.

According to Seligman (2011), a meaningful life involves feelings of belonging and serving something bigger than yourself. We are all born with a deeply rooted need to find meaning.

Frankl (2006) explains this phenomenon as the will to meaning, which refers to the intrinsic motivation to find answers and explanations for life events.

How does meaning affect us?

People who believe their lives have meaning are happier, have higher life satisfaction, are more engaged in their work, have a better immune system and buffer against stress, and live longer in general (Steger, 2009).

According to Martela & Steger (2016), meaning in life involves three main components:

Significance

You feel significant when you can contribute or make a difference. Breaking down the word significance — a “SIGN” of importance. Experiencing how strengths and behavior make a difference in life, is an example of putting significance into practice.

Purpose

“Those who have a ‘why’ to live can bear with almost any ‘how’” – Nietzsche. This quote describes the essence of purpose. Having a direction in life or core goals makes you experience purpose. Journaling about goals and achievements increases awareness of this specific facet of meaning.

Coherence

Coherence describes the connection between the past, present, and future. More in-depth coherence means our own understanding and construction of the world. Creating a lifeline and reflecting on events that have influenced your life is an empowering exercise for experiencing coherence.

Meaning-Making

Current research is also focusing more and more on meaning-making or the processes in which people engage to reduce distress and recover from stressful events (Park, 2010). There is more than one kind of meaning an individual can “make,” including:

- Global meaning

A person’s general orienting system, consisting of their beliefs, goals, and feelings; basically, global meaning is how the person views the world and the beliefs they have about how things work. - Situational meaning

Meaning in the context of a particular environment or encounter, usually a stressful one. - Appraised meaning

A subcomponent of situational meaning, the appraised meaning is the meaning a person automatically assigns to the situation; this is an implicit sort of meaning, but it can change rapidly as a person struggles to make meaning of a stressful event.

There are as many unique ways to make meaning as there are people in the world, but there are some useful categorizations to better understand the most common processes. Four distinctions between meaning-making processes have been identified and studied:

Automatic vs. Deliberate

Meaning-making can be either automatic or deliberate; an individual can engage in meaning-making unconsciously, without even being aware of it, or they can deliberately engage in the process to make meaning out of their situation.

Automatic meaning-making happens when, for example, a person experiences a stressful event and they have intrusive and unwanted thoughts of the event pop up. While this experience is not a pleasant one, it may actually help the person to make sense of their stressful event and find meaning in their suffering.

Deliberate processes can be engaged in several different ways, including coping activities. Individuals who engage in these coping activities use positive reappraisal, revise their goals and seek solutions to their problems, or activate spiritual beliefs and experiences to help them survive their difficult experience (Park, 2010).

Assimilation vs. Accommodation

When a person has encountered a stressful event and their global meaning does not match their appraised meaning of the situation, something has to change. That change can occur in their global meaning (a change in the individual’s meaning frameworks or understanding of the world), their appraised meaning of the situation (a change in how they interpret the stressful event), or both.

When an individual changes the situational meaning to be more in line with their global meaning, they are using assimilation. When the individual changes their global meaning to make room for this new situation that doesn’t “fit” with their current understandings, they are using accommodation.

It was generally thought that individuals used assimilation more since it did not require them to change their overall beliefs; however, accommodation may actually be more common, especially in the face of huge, life-altering events (Park, 2010).

Searching for Comprehensibility vs. Searching for Significance

This distinction is made between the attempt to make an event “fit” with a certain system of rules and standards, and the attempt to find significance, value, or worth in an event.

For example, a person who has suffered a tragic loss may search for comprehensibility by reminding herself that terrible things often happen to good people. Alternatively, she could search for significance by wondering what impact the loss will have on her life, and how it will change who she is as a person (Park, 2010).

Cognitive vs. Emotional

Cognitive processes are those which focus on processing the information from the stressful event and re-evaluating or reworking one’s beliefs. On the other hand, emotional processing is more focused on experiencing and exploring one’s emotions about the stressful event. These emotions must be absorbed and processed before the individual can continue on with their life (Park, 2010).

Outcomes

These meaning-making processes can lead to discovered or enhanced meaning in many different forms, including (Park, 2010):

- The sense of having “made sense,” or come to an understanding of why the stressful event happened (even if the “why” is simply “shit happens”).

- Acceptance, or coming to terms with the event.

- Reattributions and causal understanding, or coming to a conclusion about the cause of the event.

- Perceptions of growth or positive life changes.

- Changed identity/integration of the stressful experience into one’s identity.

- Reappraised meaning of the stressor, or bringing the experience in line with one’s current global meaning.

- Changed global (or overall) beliefs about the way things are in the world.

- Changed global (or overall) goals, such as abandoning unattainable goals or creating alternative goals.

- Restored or changed sense of meaning in life.

However researchers define, distinguish, or dissect the concept, they generally all agree that the more meaning we experience in our lives, the better.

25 Examples of Meaningful Experiences

If you’re thinking that you’d love to encounter more meaning in your life but you’re not sure where to look, you’re probably already thinking about it too much!

Meaning can be found in every single encounter and interaction that we have.

However, if you’re like me (i.e., the kind of person who appreciates lists), check out these lists of some of the most meaningful experiences in life.

Positive Experiences

Meaningful, positive experiences can be found in many different contexts, but some of the most common and impactful experiences include:

- Falling in love

- The birth of a child

- The birth of a grandchild

- A reconciliation or reunion with a loved one

- Immersing yourself in a new culture or way of life

- The first time you make a big, life-altering decision for yourself

- Showing someone the depth of your feelings for them, or receiving this expression of feelings

Although the big ones are likely the ones your mind went to first, meaning can also be found in many of the small moments in life, such as (“9 Meaningful Moments”, 2014):

- A child taking your hand for the first time, or giving you a completely voluntary and enthusiastic hug

- Running into a friend you haven’t seen in a while

- Experiencing a new culture on a vacation or humanitarian trip

- A loved one expressing their gratitude for you

- Coming home to a happy, loving pet

- Quitting something that makes you unhappy

- Enjoying some unexpected time alone

- Realizing you’ve mastered a difficult skill

- Hopping in the car for a spontaneous road trip

Remember to pause and look for meaning in moments big and small. It’s so often the little moments that we remember for years after we experience them.

Negative Experiences

While we’d all love to maximize our positive experiences and avoid the negative ones, that would lead to incredibly unbalanced people! It is often during these negative, stressful, and challenging times that we find out where our strengths lie, how to push further than we have ever pushed before, and how to truly thrive.

Some of the significant negative experiences that can lead to profound meaning include:

- The death of a loved one

- Divorce, separation, or another break in a relationship

- Loss of a job (getting fired or laid off)

- Natural disaster (e.g., flood, fire, avalanche)

- Becoming the victim of a crime

- Suffering a trauma (e.g., soldiers in combat or witnesses of extreme violence)

- Near-death experiences

- Sustaining serious injuries

- Getting diagnosed with cancer or a debilitating disease

For all of these experiences, you have probably heard at least one or two stories about someone finding meaning in their trauma or stress.

The important thing to take away from this discussion of meaningful experiences is that the definition of “meaningful” can vary widely; some people will find significant and life-changing meaning in situations in which others would simply shrug and move on with their life.

If you didn’t find some of the experiences on these lists to be meaningful, don’t worry! Meaning is an intensely personal thing, and we all find it in different places and in different forms.

What is The Meaning of Life?

“The sole meaning of life is to serve humanity.”

Leo Tolstoy

“For the meaning of life differs from man to man, from day to day, and from hour to hour. What matters, therefore, is not the meaning of life in general but rather the specific meaning of a person’s life at a given moment.”

Viktor Frankl

So, now that we’ve covered a few of the biggest theories and frameworks of meaning across philosophy and psychology, we should now be able to answer the big question:

What is the meaning of life?

As unsatisfactory as you may find this answer, it seems that the meaning of life is different to each and every one of us.

We may find ultimate meaning in the love of a spouse or a child.

We may find it in the work that we do.

We may discover that volunteering and giving back in our community is the activity that gives our life the most meaning.

We might even discover that Viktor Frankl was spot-on with his theory of meaning and that our attitude towards what happens to us is the source of meaning in our lives.

Wherever we find purpose and fulfillment, it seems that it is truly up to us to tease out that which is the most important, the most life-giving, and the most significant. Within this soup of values, experiences, goals, and beliefs, we can piece together that which gives us the best sense of meaning in our own lives.

4 Books About Meaning (of Life)

If you are still wildly unsatisfied with this answer on the meaning of life, perhaps this list will help!

It’s difficult to narrow down a list of the best books on meaning; after all, humans have been writing about life’s meaning for as long as writing has been around! There is quite a bit of material on this subject, so consider this a very, very short list of some of the most helpful, insightful, and/or humorous books on finding meaning in life.

1. Man’s Search for Meaning – Viktor E. Frankl, William J. Winslade and Harold S. Kushner

The seminal work on Frankl’s meaning model, this book is a life-changing experience for many who read it. Written in the form of a memoir, this book guides the reader through Frankl’s experiences in four concentration camps, including the infamous Auschwitz.

Frankl suffered more than most of us will ever suffer, losing his parents, his brother, and his pregnant wife, among others. Through his experience of such tremendous pain, he developed a theory of meaning that laid the groundwork for decades of research and inspired millions of readers to seek out meaning for themselves.

The first section of this book is mostly a description of Frankl’s experience in the camps between 1942 and 1945, while the second section dives into his theory: logotherapy. Throughout the book, the reader will be presented with evidence and anecdotes that show how powerful it can be to choose how you respond to suffering.

If you’re interested in reading Frankl’s bestselling book (and I highly recommend that you do), you can find it for sale.

Find the book on Amazon.

2. Every Time I Find the Meaning of Life, They Change It: Wisdom of the Great Philosophers on How to Live – Daniel Klein

This book takes a very different tone from the previous entry, but it can be just as insightful.

During his college years studying philosophy, Daniel Klein filled a notebook with quotes from some of the world’s best and brightest – quotes that inspired him, enlightened him, or struck him as excellent guidance.

In his 80s, Klein revisited this notebook and added, edited, and revised his entries, providing annotations and notes for the reader to follow along. With the wisdom and experience that only age can bring, the author explores how he has changed and how he has stayed the same, and how each quote applied (or missed the mark!) in his life.

If you are looking for a book that is fun, humorous, and enlightening all at once, this may be the book for you.

Find the book on Amazon.

3. Meditations – Marcus Aurelius

Likely a familiar book for philosophy students and teachers in the humanities, this tome contains the personal writings of Marcus Aurelius, the Roman Emperor from 161 to 180 CE.

It contains twelve books, each composed of several quotations ranging from one sentence to lengthy paragraphs. While these writings were never intended to be published and distributed to the masses, they are still full of some of the most interesting and thought-provoking ideas to ever be put on paper.

Meditations includes Marcus Aurelius’ musings on life, philosophy, religion, virtue, morality, and more. It is not a quick and easy read, but it is certainly worth the effort required.

Find the book on Amazon.

4. The Bible (Old and New Testaments), the Quran, the Tripitakas, and the Bhagavad Gita

Whether you are religious, agnostic, atheistic, spiritual, or anything in between, there is something to be gained by reading these foundational works of the major religions.

If you are Christian, I highly recommend reading the Quran (the holy book of Islam), the Tripitakas (the Buddhist scriptures), and the Bhagavad Gita (one of Hinduism’s most important scriptures). Likewise, if you belong to one of the other religions on this list, I highly recommend reading the holy books of the other major religions.

It is so easy to get stuck in one way of thinking or being, and missing out on life-changing knowledge and insight that can be found in places you wouldn’t even think to look. Even if you think you know all there is to know about another religion or denomination, you will certainly learn something new by branching out your religious readings.

While you will likely not agree with all (or even most!) of the rules, laws, or morals outlined in each book, reading them will give you a sense of what humanity has found important, meaningful, and significant for the last few thousand years. You will notice interesting overlaps between the belief systems, and notice what they have in common (like the famous Golden Rule).

Making your way through each book will be challenging, but the reward is a deeper understanding of each religion, of humanity itself, and of your own sense of meaning in the world. It can’t hurt to read at least a few pages, right?

A Take-Home Message

I hope you come away from this piece with a broader sense of what “meaning” is, how humans attain it, and how it impacts us. I hope you also found at least one new theory or reading recommendation that sparked your interest.

Meaning is one of the few things that you simply cannot over-consume; having a more meaningful life is always a worthwhile pursuit, and you can never become too fulfilled or too full of purpose!

What do you think about meaning in life? Is there a purpose to life that I completely missed? What do you personally find meaningful in your life? Let us know in the comments!

Thanks for reading!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free.

[Reviewer’s Update]

Since this post was originally published, there have been several good-quality studies on the topic. If you’re interested in further reading, we’d recommend “The Science of Meaning in Life” (King & Hicks, 2021) and “Making Time Matter: A Review of Research on Time and Meaning” (Rudd et al., 2019).

- “9 Meaningful Moments.” (2014). 9 meaningful moments you should really be paying attention to. Huffington Post Parents. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08/19/meaningful-moments_n_5537455.html

- Burnham, D., & Papandreopoulos, G. (n.d.). Existentialism. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/existent/#SH1f

- Duignan, B. (n.d.). Postmodernism. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/postmodernism-philosophy

- Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

- George, L., & Park, C. L. (2016). Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Review of General Psychology, 20, 205-220.

- Good Therapy. (2015). Logotherapy. Good Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/logotherapy

- “History of Modernism.” (n.d.). Miami Dade College Humanities Department. Retrieved from https://www.mdc.edu/wolfson/academic/artsletters/art_philosophy/humanities/history_of_modernism.htm

- Irvine, M. (2013). Approaches to po-mo. Georgetown University Communication, Culture, & Technology Program. Retrieved from http://faculty.georgetown.edu/irvinem/theory/pomo.html

- King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 72, 561–584.

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531-545.

- Mattiuzzi, P. G. (2015, March 2). Meaning and purpose in life: Commonplace or hard to come by? Huffington Post Blog. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/paul-g-mattiuzzi/meaning-and-purpose-in-li_b_6398216.html

- Nordquist, R. (2017, April 3). Meaning semantics. Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/meaning-semantics-term-1691373

- Park, C. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 257-301. doi:10.1037/a0018301

- Rudd, M., Catapano, R., & Aker, J. (2019). Making time matter: A review of research on time and meaning. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 29(4), 680–702.

- Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A new understanding of happiness and well-being and how to achieve them. Nicholas Brealey.

- Steger, M. F. (2009). Meaning in life.

- West, R. (2007). Meaning. Urban Dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=meaning

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (56)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (17)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (39)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (44)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (13)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (42)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (22)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)

What our readers think

This message opened my mental eyes am real appreciate you thank you ,,thank you againi 🙏🙏🙏🙏

Hi. Thank you for this information.

Great blog.

thank you so much for this powerful information. I have a question which date and year does this website published?

Hi Aisha,

Glad you found the information useful. This article was published on the 6th of February, 2018 🙂

– Nicole | Community Manager