38 Best Coaching Tools and Assessments To Apply With Clients

As with many practices carried out today, the origins of coaching as we know it has roots stretching back to ancient Greece.

As with many practices carried out today, the origins of coaching as we know it has roots stretching back to ancient Greece.

Providing some of humanity’s earliest recorded forays into the world of coaching and coaching theory, the renowned ancient Greek philosopher Socrates methodically asked questions and engaged in dialogue to derive truth and knowledge.

Aristotle believed that a life goal is the pursuit of wellbeing through the development of virtues.

From these tentative beginnings, the 20th century saw exponential growth in coaching within personal, health, workplace, and executive settings; evolving from a practice initially met with derision to a well-researched, mainstream activity practiced virtually worldwide.

In the following article, we take a look at the theory of coaching, some effective exercises, and activities that can be applied to your coaching sessions, and worksheets and other resources to help you shape and tailor your programs to meet your clients’ needs.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- A Look at Coaching Theory

- Examples of Effective Coaching

- 5 Coaching Ideas You Can Try Today

- Coaching Assessment Tools

- 5 Activities to Implement into your Coaching Practice

- 5 Coaching Interventions

- 23 Useful Worksheets

- Pre-Coaching Questionnaires

- Tests for Coaches to Sharpen their Skills

- More Relevant Resources (on our blog)

- A Take-Home Message

- References

A Look at Coaching Theory

Coaching is grounded in cognitive and behavioral learning theories. The most effective coaching practice integrates classical conditioning, reinforcement, transformative learning, and experiential learning theories in order to make lasting changes through the process of deep learning.

Fazel (2013) suggested that without understanding learning theories, coaching cannot effectively facilitate learning and results, thus coaching practice could potentially collapse into a theoretical abyss.

The theory of coaching has its roots in a multitude of disciplines, including philosophy, sociology and anthropology, sports, and communication science.

While much initial research focused on examining and developing effective coaching practices in the areas of sports and clinical psychology, recent decades have seen burgeoning research in the fields of coaching psychology and positive psychology – two fields that focus on performance enhancement, positive aspects of human nature, and the strengths of individuals (Passmore, 2010).

Therefore, it was surmised that positive psychology may offer a solution to the lack of theoretical foundation and provide a robust framework for coaching research.

In essence, we can see that coaching is effective, but why is it so? What psychological mechanisms are employed and how can we adapt coaching practices to maximize its effectiveness across contexts?

Kemp (2004) described coaching as the application of positive psychology, while Seligman (2007) suggested that positive psychology is the undeniable theoretical backbone of coaching. He theorized that successful coaching interventions should incorporate three fundamental concepts behind positive psychology so as to limit the scope of practice, namely: positive emotions, engagement, and meaning.

Examples of Effective Coaching

Coaching is a valuable tool for developing a wide range of skills; essentially providing a space for profound personal development, and allowing managers to translate personal insights into improved organizational development (Wales, 2003).

Coaching has been found to improve self-awareness, self-acceptance, wellbeing, the ability to manage stress, communication and leadership skills, goal attainment, self-confidence, and a plethora of other beneficial outcomes (Fazel 2013). So, what are the essential components of effective coaching?

1. Trust

Coaching by its very nature is based on trust. Establishing and maintaining a trusting relationship is fundamental to enhancing the coaching process. In a coaching relationship with mutual trust, those being coached will have confidence in the process while the coach, in return, will have confidence in the commitment of the coachee.

If there is no trust, it follows that rapport and confidence in the coach will also suffer – as will the effectiveness of the coaching process. It stands to reason that we’re more likely to take on board the lessons offered when we perceive them to be coming from a competent, knowledgeable source. Moreover, as coaches (and human beings) it’s easier to work with those who are receptive and positively engaged with the process.

From a neurological perspective, altruism, empathy and other pro-social behaviors can trigger the release of oxytocin, a hormone associated with bonding. In turn, bonding can positively influence the self-evaluations of wellbeing and measures of trust, thereby creating an open and honest coaching environment (Kosfeld, Heinrichs, Zak, Fischbacher, & Fehr, 2005).

Regardless of the experience and skill level possessed by a coach, in the absence of trust, a coachee will struggle to be open, honest, and reflective. Additionally, if the coach-coachee relationship is poor, it is likely that the client’s level of confidence in their own ability to achieve goals will be reduced (de Haan, Grant, Burger, & Eriksson, 2016).

2. Clarity & Client Accountability

Clarifying expectations in the initial stages of coaching is integral to effective outcomes. According to Schmidt (2003), coaching failure can occur when the coachee is not willing to reflect and/or refuses to take responsibility for their development and actions.

Furthermore, if the coachee has high or unreasonable expectations of the coaching process and delegates all responsibility for progress to the coach, the relationship is unlikely to succeed.

Schmidt (2003) also indicated that ample time should be invested at the beginning of a program in order to establish transparency about the coaching process and the responsibilities of each party. In this way, the foundation is set for a solid understanding of what lies ahead and the risk of misunderstandings and failure is minimized.

3. Goals

Coaching is, at its core, a goal-driven activity. Research on goal-setting (Latham & Locke, 1991) emphasizes the importance of goals that are specific and challenging yet attainable. An effective coach is one who ensures that client goals meet this criterion while also anticipating potential obstacles that could prevent the achievement of those goals.

Creating goals and action plans improves performance and facilitates goal attainment. Grant (2014) found that a goal-focused coach-client relationship was a powerful predictor of coaching success and that goals initiated by the client rather than the coach were positively related to successful coaching outcomes.

Coaches should guide their clients carefully through the goal-setting process, evaluating and possibly abandoning goals that seem unlikely to be achieved. For instance, clients can be asked to rate on a scale of 1 to 10 how committed they are to a particular goal.

If the client clearly lacks interest or commitment, the coach can then help to identify and focus on more important goals (Gregory, Beck, & Carr, 2011).

4. Feedback & Assessment

In order to initiate and sustain behavioral change, it is imperative that a coachee receives information regarding their progress or lack thereof (Gregory, Beck & Carr, 2011).

A large number of studies have emphasized the importance of feedback for effective coaching, with many deeming it an integral activity within the coaching process that reveals discontinuity between desired and current performance (Ellinger & Bostrom, 1999).

Kluger & DeNisi (1996) suggested that effective coaches are those who are mindful of the type of feedback that they communicate. When providing feedback, coaches should choose language carefully so as to facilitate motivational and behavioral changes (see our motivation tools) and to help clients recognize that even negative feedback has value.

5 Coaching Ideas You Can Try Today

In coaching, sometimes less is more. Some of the most effective coaching exercises are often minimalist in design. The following are some simple coaching ideas that can be easily incorporated into your coaching practice in order to develop and support communication and sustain a strong connection between you and your clients:

1. The Wheel of Life

The Wheel of Life is a simple yet effective coaching tool that allows clients to form an understanding of where they are currently and where they would like to be in the future.

Through the evaluation of different life aspects and current goals, the Wheel of Life encourages self-reflection, helps your clients gain insights into their life balance and life satisfaction levels, and identify their strengths and weaknesses.

As a coach, you can utilize this exercise to help your clients delve into why their wheel of life looks the way it does, what they would like their wheel to look like, and how to make these changes happen.

Life satisfaction is measured along with predefined life domains, typically these include areas such as: finance, career, health & fitness, recreation, community, relationships, love, personal growth, spirituality, and physical environment.

When the client’s life domains have been identified, they will then rate them individually on a scale of 0-10 so as to reflect their level of satisfaction within that particular area. After the assessment is complete, both the client and the practitioner have a visual representation of life satisfaction.

From this, clients can form an understanding of where they are currently, where they would like to be in the future and importantly, what domains require the most attention.

2. The ‘Three Good Things’ Gratitude Exercise

The expression of gratitude has been shown to contribute to positive emotions, and in turn to overall wellbeing (Emmons & McCullough, 2003).

The Three Good Things exercise (Seligman, 2005) is an effective way to promote wellbeing through the regular practice of gratitude. The basic premise of the exercise is simple; think about and write down three positive things that have happened today and causal explanations for why they happened.

The effectiveness of Three Good Things hinges on reflection and repetition. The degree to which clients continue with the exercise mediates the long-term benefits. Seligman, Steen, Park & Peterson (2005) found that completing the exercise regularly over one month resulted in an increase in happiness with the positive effects enduring at three and six-month follow-ups.

You can learn more about this exercise in the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

3. One Door Closes, One Door Opens

Alexander Graham Bell once surmised:

When one door closes another door opens, but we so often look so long and so regretfully upon the closed door, that we do not see the ones which open for us.

This quote perfectly encapsulates the ethos behind the One Door Closes exercise.

Developed by Rashid (2008), One Door Closes is an effective way to develop optimism and reframe negative events in a more positive way.

In this exercise, invite clients to think back over their life and think of an occasion when they were unsuccessful in achieving their objective. The client is then invited to consider and write down the positive things that happened as a result of the first door closing; thus reframing negative outcomes in a positive manner.

This exercise can also be practiced by the client outside of the coaching setting. Rather than thinking back over an entire lifetime, clients can carry out the exercise regularly throughout their weekly routine, asking the question: What failure led to unforeseen positive consequences?

4. The Coping Strategies Wheel

Effective coping strategies are an important mediator between negative life events and psychological wellbeing (Herman-Stahl, Stemmler & Peterson, 1994).

Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck (2007) identified 12 common hierarchical categories of coping. These include problem-solving, support-seeking, escape, distraction, cognitive restructuring, rumination, helplessness, social withdrawal, emotional regulation, information-seeking, negotiation, opposition, and delegation.

The coping strategies wheel can be used to detect adaptive or non-adaptive coping strategies – this information can then be drawn upon to consider and introduce more effective strategies.

Check out the Positive Psychology Toolkit to learn more about the Coping Strategies Wheel and how best to use it in your coaching process.

5. Using Strength in a New Way

Using strengths in new ways has long-term positive effects on happiness, wellbeing, stress, vitality, self-esteem and positive affect (Seligman, Steen, Park & Peterson, 2005; Wood, 2010).

To begin this exercise, clients should select one of their top strengths and identify where this strength is already in action, then endeavor to practice the strength in a novel way at work, home, or leisure. The coachee should commit to using this strength in new ways, every day for one week.

Coach and client can discuss areas in which this signature strength can be applied to improve or make the most of a given situation. For instance, how might a client use the strength of gratitude to center themselves in the face of public speaking anxiety? Or use the strength of curiosity to engage with new people?

Want to bring out the best in people? Start with strengths

Coaching Assessment Tools

One of the best mechanisms for determining outcomes is to provide pre- and post-assessment measures. A wide range of tests, scaling techniques and questionnaires can be used to assess client strengths, progress, goal setting, and satisfaction in relation to their desired outcomes, or to clarify their commitment going forward.

1. Process Evaluation Scale (PES: Ianiro, Lehmann-Willenbrock, & Kauffeld, 2014)

The PES is a useful tool to assess coachee goal attainment. Respondents are asked to rate their current degree of goal achievement on a scale of 1 (not at all achieved) to 10 (fully achieved).

When taken regularly, for instance at the beginning of each session, average values can then be calculated across all defined goals for each client. The client’s success in attaining their individual goals can be understood in terms of progress and overall goal attainment.

Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) is another option that can be used as a means of assessing coaching outcome data. GAS enables the measurement of qualitative goal attainment by incorporating a quantitative measurement via a 5-point Likert scale where goal attainment is measured from -2 (worst expected outcome) to +2 (best-expected outcome).

While the PES and GAS have proven to be effective in the evaluation of progress towards program-specific goals (MacKay & Lundie, 1998), it is noteworthy that, as with many self-report instruments, these assessment tools are susceptible to distortion and bias due to performance rationalizations.

2. The VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS: Peterson & Seligman, 2004)

Developed as a method to assess individual values and strengths, the VIA-IS can be an illuminating experience for both the client and coach. Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi (2000) stated that much of the best work carried out in the consulting room amplifies the strengths rather than the weaknesses of clients.

Linley et al., (2010) explored the connections between strengths use, goal progress, psychological needs, and wellbeing. The results from this study suggest that those who utilized their signature strengths made more self-concordant goals, more progress toward their goals, and exhibited greater overall wellbeing.

That isn’t to say that values for which a client registers a low score should be ignored, rather the most positive outcomes arise from coaching interventions which seek to promote those skills already in abundance.

3. The Leader Competency Inventory (LCI: Kelner, 1993)

The LCI is a self-report method for measuring an individual’s use of four specific dimensions of leadership – information seeking, conceptual thinking, strategic orientation, and service orientation.

Respondents are asked to state the degree to which they have demonstrated or seen various behaviors. The LSI can be particularly beneficial in business and executive coaching to increase a leader’s impact, and to measure, strengthen and develop leadership skills.

4. The Leadership Skills Inventory (LSI: Karnes & Chauvin, 1985)

The LSI is a 56-item self-assessment designed primarily for leaders, encouraging them to assess their own abilities in relation to five dimensions of leadership: self-management skills, interpersonal communication skills, consulting skills for developing groups and organizations, and versatility skills.

Clients are asked to respond using a 10 point scale ranging from “This skill is new to me” to “I can perform the skill well. I can teach others, too.” The LSI has shown concurrent and construct validity and is an effective assessment of leadership skills (Edmunds, 1998).

5. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS: Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985)

The SWLS is a 5-item scale designed to measure cognitive judgments of life satisfaction. Respondents indicate how much they agree or disagree with each statement on a 7-point scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

The SWLS is a valid and reliable measure of life satisfaction that is suitable for use within a wide range of age groups and applications. Additionally, the satisfaction scale has shown sufficient sensitivity to be effective in the detection of change and the tracking of progress in terms of life satisfaction during the course of coaching interventions (Pavot, Diener, Colvin, & Sandvik, 1991).

5 Activities to Implement into your Coaching Practice

The activities you implement can have a huge impact on the effectiveness of your coaching. Thinking of novel ways to assist in goal setting, motivation, and progress tracking can be onerous and time-consuming, so we’ve done some of the hard work for you. The following activities can be used to add a little variety or a fresh approach to your coaching sessions.

1. Goal Visualization

As people approach a goal, external representations, which increase the ease of visualizing the goal, enhance goal pursuit (Cheema & Bagchi, 2011). Specifically, easy-to-visualize goals are perceived to be more attainable and therefore encourage greater effort and commitment than goals that are more difficult to envisage.

Effective in varied contexts, the visualization of goal progress also enhances motivation as people approach their goal, which in turn increases effort and commitment.

As with the key goal-setting principles set out by Locke & Latham (1991), the goals set within a coaching context should be challenging yet attainable – the beneficial effects of visualization exist only when people are close to the goal (Cheema & Bagchi, 2011).

The Goal Visualization tool, available as part of the Positive Psychology Toolkit©, aims to increase expectations for success, enhance motivation and emotional involvement, and initiate planning and problem-solving actions through the promotion of goal-directed behavior. The aim, as shown below, is to use imagery to help clients cultivate a mental vision based on positive expectations, which is more motivating than positive fantasy.

In this image, we’ve used the online coaching app Quenza to share the mp3 with our clients, so they can repeat the exercise as homework. This will further strengthen their goal-related mental imagery, thereby increasing their motivation.

In order to visualize a goal it is essential that the objective is considered carefully; be it personal, educational, or work-related the goal must be specific and clear in order to visualize it effectively.

Once a goal has been set, the coach should ask the client to imagine their future selves and the steps they could take in the process of achieving their goal: in four weeks what decisions will they have made to move forward in achieving the goal?

In six months when/if they are closer to achieving their goal, how does that make them feel? Visualize the achievement of that goal; what emotions are you experiencing? Where are you? What are you doing?

Goal visualization is essentially thinking about the objective and the actions required to achieve it. Imagining not only the end goal but also the incremental stages in reaching said goal encourages reflection on the process involved.

By looking back on an imagined journey to success, clients can better consider the strategies they might use, the personal challenges they might face, and the day-to-day changes they can make in order to achieve their objective.

2. Motivational Interviewing

Developed by Miller and Rollnick (2002) motivational interviewing (MI) is a collaborative and self-directed process that emphasizes the client/coachee as being ultimately responsible for making and sustaining change. It involves the application of four basic principles, expressing empathy, developing discrepancy, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy.

MI lays the foundation for effective coaching practice by encouraging the client to reflect on their current behavior, its wider effect on their colleagues, friends, and family, and encouraging long-term and intermediate goals (Greif, 2007).

According to Miller & Rollnick (1991) an effective motivational interviewer should:

- Express empathy through reflective listening.

- Develop a discrepancy between clients’ goals or values and their current behavior.

- Avoid argument and direct confrontation.

- Adjust to client resistance rather than opposing it directly.

- Support self-efficacy and optimism.

3. Personal Goal Progress Review

As previously discussed goals and goal-setting within the coaching process is integral to coaching efficacy. According to goal setting theory (Locke and Latham, 1991), goal setting is most effective in the presence of unambiguous feedback which allows progress to be monitored frequently and for reassessment when required.

The Personal Goal Progress Review is a self-reflection tool that will assist clients in monitoring progress towards goal attainment by regularly reviewing the progress they have made in a mindful way, without self-judgment.

Together with the client think of a few essential questions that will help track their progress, for instance:

- What tasks did I complete in the last month that I am proud of?

- What are my goals for the next month?

- What problems have I faced? Have these been resolved?

- What is still to be achieved? What do I need to do to achieve these goals?

The responses to these questions should be reviewed on a monthly basis in order to consistently monitor goal progress.

Check out the Positive Psychology Toolkit© if you would like to access and learn more about the Personal Goal Progress Review.

4. Reflective Journaling

According to Colton & Sparks-Langer (1993) reflective journaling:

- Serves as a permanent record of thoughts and experiences.

- Provides a means of establishing and maintaining a relationship with instructors.

- Serves as a safe outlet for personal concerns and frustrations.

- Serves as an aid to internal dialogue.

Reflective self-evaluation has been shown to positively impact both intellectual growth and self-awareness, indicating that positive perception and deep understanding of one’s emotions, strengths, and weaknesses allows individuals to stand back and reflect on their actions (Palmer; Bums & Bulman, 1994).

Client reflections can be reviewed and revisited at any time, thus progressive clarification of insights is possible (Hiemstra, 2001). The inclusion of journaling during the coaching process allows clients to chronicle their growth, development, and success. When pre-agreed milestones are achieved both client and coach can see the actions that led up to that accomplishment.

Taking some time to write down thoughts, ideas and emotions make them tangible and real, thus allowing clients to take a new perspective and observe themselves from a distance.

You can find a helpful selection of reflective writing prompts for free here.

5. The Emotion Meter

Developing Emotional Intelligence is about acquiring the skills to manage emotions – both the negative and the positive. Emotional intelligence improves one’s ability to communicate and more effectively relate with others, solve problems more readily, manage change and build trust (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, 2006).

Individuals who have difficulty identifying their emotions may consequently lack the ability to become aware of emotional states that would benefit from regulation in everyday life.

The Emotion Meter exercise is designed to develop the skills of recognizing and labeling emotions by helping clients track their emotions at regular points throughout the day. Clients are invited to connect with their current emotional experience, paying attention to any physical sensations they may experience.

After careful observation of their current emotional state, the pleasantness of the emotion and their current energy levels are rated on a scale of 1 to 10. The scores collated here will match an emotion on the emotion meter, for instance, a pleasantness score of 7 and an energy score of 8 corresponds with being focused, while a pleasantness score of 3 and an energy score of 7 corresponds with feeling worried.

Developing emotional self-awareness takes practice. Over time, this exercise can become an intuitive and powerful tool for clients to acknowledge their emotional state, recognize the emotions that they are experiencing, and expand their emotional vocabulary.

If you are interested in learning the skills required to professionally coach emotional intelligence, check out the Emotional Intelligence Masterclass©.

5 Coaching Interventions

The following interventions are excellent suggestions to apply in your coaching sessions.

1. Mindfulness Intervention

Mindfulness and coaching as a methodological partnership have attracted theoretical and research interest, the results of which indicate the efficacy of mindfulness practices when applied to the coaching context – both for the coach and the client (Spence, Cavanagh & Grant, 2008).

This is perhaps unsurprising when you consider the importance of in-the-moment attention and non-judgmental awareness in both mindfulness and in effective coaching practices.

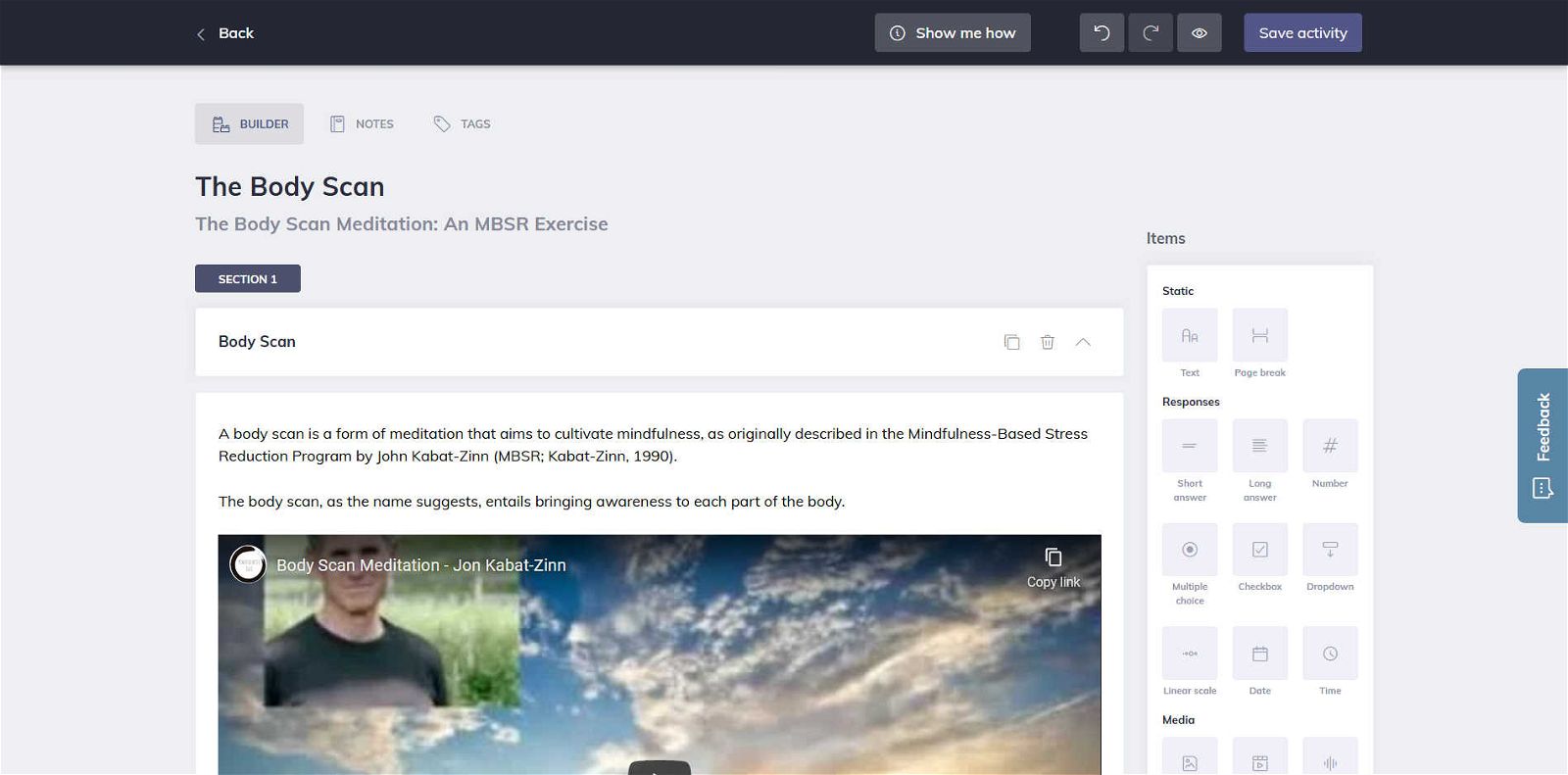

There are many methods by which mindfulness can be incorporated into the coaching paradigm, one of which is the Body Scan Meditation. Like many guided meditations, breathing exercises, and other mindfulness interventions, the Body Scan works particularly well when used as an online coaching tool:

The body scan has been associated with a perceptual shift in which thoughts and feelings are recognized as events occurring in the broader field of awareness. This flexible exercise can be applied face-to-face, or digitally using coaching platforms such as Quenza (pictured).

Additionally, with regular practice the body scan has been linked to decreased rumination, an increased tendency to describe experiences, and increased self-compassion (Sauer-Zavala, Walsh, Eisenlohr-Moul, & Lykins, 2013).

The body scan develops mindfulness via a number of avenues; by paying attention to different parts of the body in turn, deliberately engaging and disengaging attention, and by becoming aware of – and relating differently to – positive and negative mental states.

You can learn more about this exercise and coaching mindfulness in the Mindfulness X Masterclass.

2. Motivational Awareness Intervention

The Daily Motivational Awareness intervention is used to increase client awareness of motivation and the extent to which the motivation of daily activities is self-determined.

A client who understands that they can impact their own motivational levels is better equipped to adopt the practices required to maintain momentum toward their goals.

The motivational awareness exercise is simple to administer and complete; clients are invited to notice what motivates them throughout their daily activities and to consider the factors that influence it.

At random times throughout the day, clients should think about their responses to three “awareness” questions: What am I doing? Why am I doing this? Where is it taking me?

Reflections on these questions are then recorded and act as a way to reflect on their behavior in terms of motivational orientation.

3. Appreciative Inquiry

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is an effective intervention that can provide opportunities for coaches to facilitate client learning processes more effectively. AI was described by Cooperrider (1986) as an approach that allows a client to experience a process of transformation through the exploration and discovery of their strengths and positive potential.

The appreciative coaching approach develops a foundation for constructing transformative changes in a positive way; moving thinking and language away from a deficit (negative) orientation and toward more appreciative (positive) orientation.

The appreciative coaching approach can influence the client’s learning experience by deepening their appreciation of their unique contributions and accomplishments and creating sustainable solutions through collaborative discovery (Suess & Clark, 2014).

4. Giving Negative Feedback Positively

According to Cleveland, Lim, & Murphy (2007), the only task more difficult than receiving performance feedback is giving performance feedback.

Despite this, constructive feedback has many positive benefits, including revealing obstacles that must be confronted if future success is to be achieved. Remember also, that there is probably greater potential to learn from our mistakes than from our successes.

Folkman (2006) offered some general advice on approaching negative feedback with coaching clients:

- Focusing on the problematic behavior or action rather than the person will minimize the risk of the feedback being interpreted as a personal attack.

- Be constructive, specific, and non-judgmental.

- Mutually explore future avenues for improvement or change.

You can find additional guidance on the process of reframing negative feedback in a valuable way in the Positive Psychology Toolkit.

5. Strengths-Based Intervention

Research suggests that strength-based interventions are a significant predictor of change in transformational leadership behavior.

MacKie (2013) found that strengths-based approaches offer an effective leadership development methodology. The strengths approach in coaching encourages development by building on existing strengths rather than attempting to ameliorate weaknesses; consider what’s strong rather than what’s wrong.

It is likely that clients will feel more positive about the coaching process if they consider their strengths and how they could develop them further rather than making up for their perceived weaknesses.

In fact, working to our strengths feels better and is far more motivating than working on weaknesses (Kauffman, 2006). For instance, compare the following approaches and consider how you would respond as a client:

A Deficit Approach

1. Think about an aspect of your work that you find burdensome and struggle to do well.

2. Formulate a 12-month goal for yourself to bring your performance in this area to an adequate level.

3. Notice how you are feeling.

A Strengths Approach

1. Think about an aspect of your work that you enjoy and are good at.

2. Formulate a 12-month goal to develop your competence in that area further.

3. Notice how you are feeling.

23 Useful Worksheets

For further assistance with your coaching, below is a selection of useful worksheets to use with your clients.

Goal Setting

This compilation contains five workbooks and worksheets from the Positive Psychology blog that will help you guide your clients in setting effective life goals and monitoring progress towards goal attainment.

Self-Confidence

For many coaches, an important aspect of the coaching process is the clients’ journey towards greater self-confidence. You can find a selection of five worksheets designed to improve self-confidence through the exploration of strengths, core beliefs, and self-esteem.

Emotional Intelligence

If you’d like to introduce emotional intelligence to your coaching practice, this collection of six EI worksheets and five workbooks is jam-packed with ways you can help educate clients on the importance of emotional intelligence, enhance self- and social- awareness, and improve self-management skills.

Reflective Journaling

This free worksheet is great for coaches who would like to introduce reflective journaling to their coaching practice. The exercises included provides thought-provoking prompts to help your clients better focus their attention on self-reflection and make the reflective writing process a little easier.

This self-reflection worksheet forms part of a larger article containing a plethora of self-reflection questions, exercises, and tools. The aim of this worksheet is to help your clients think about their values, strengths, and motivations.

Pre-Coaching Questionnaires

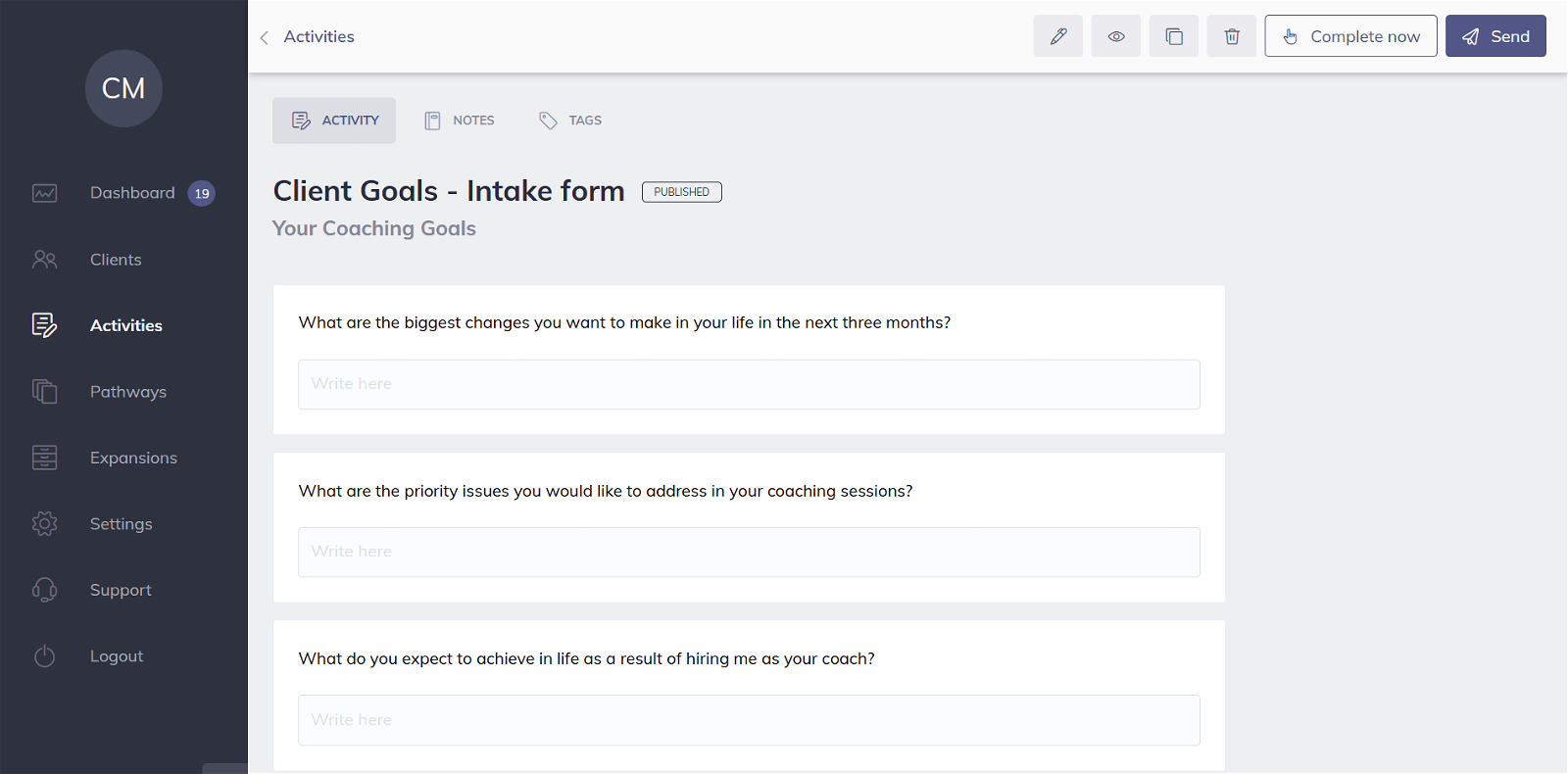

The inclusion of pre-coaching questionnaires is integral to accurately identify performance levels at the beginning of the coaching process in order to achieve valued professional or personal outcomes.

There are various methods by which this can be assessed, for instance, diagnostic interviews or face-to-face interviews; however, the pre-coaching questionnaire is an effective and less time-consuming strategy to garner this information.

Pre-coaching questionnaires are designed to focus on specific areas of performance linked to specific coaching objectives. The results of which provide feedback at the beginning of the coaching program which can then be used as a starting point in agreeing on objectives and future actions (Cooper, 2009).

Many coaches incorporate questionnaires into their pre-coaching ritual as a way of ensuring clients are adequately prepared for – and committed to – taking action.

Comprehensive pre-coaching questionnaires are an efficient way to determine a client’s needs and expectations prior to coaching and to monitor progress throughout the coaching process.

The most important aspects of the questionnaire are 1) ensure the questions you ask are relevant, and 2) use the information provided to follow up on those questions. The pre-coaching questionnaire isn’t just an empty exercise; the information should be used to shape your approach.

Questions should be tailored to your specialty and be created specifically to increase your knowledge of the client, but also to help raise your client’s awareness of what they are truly seeking.

Before administering the survey, a pre-test will help identify confusing questions and increase validity and reliability. If possible, individuals in the pre-test group should be similar to those who will complete the survey when it is finished. Sharing this with clients online before an initial appointment will give you time to plan a more personal intake session with custom goals and self-reflection prompts:

The following questions/statements will help guide you in creating your own coaching questionnaire, as we have done above using Quenza’s custom Activity Builder:

- What are your expectations from the coaching program?

- What are the three biggest changes you would like to make in your life?

- List three goals you would like to achieve in the next three months.

- If you could change one thing in your life right now what would it be?

- How willing are you to do what it takes to change your situation?

- How close/far does success seem to you, in your current life/career situation?

- What would you say are your three greatest strengths?

- How would you rate your happiness on a scale of 1 to 10?

- In one sentence, how would you describe your previous year?

Tests for Coaches to Sharpen their Skills

An effective way to sharpen your skills as a coach is to identify your blind spots. We all have them, it might be an area where you lack understanding, or perhaps you need to work on giving negative feedback more effectively.

Regardless of what it may be, knowing where you need to improve will allow you to make the changes required to achieve more successful coaching outcomes.

Even if your coaching skills are good, it’s important that you strive to find ways to make them even better. There are many methods that can test your coaching skills – surveys, questionnaires, scales; they all have the same objective, to let you know what you need to do to take your coaching skills to the next level.

The Coaching Outcome Short Scale (COSS: Schmidt & Thamm, 2008) is one such method, developed as a way to assess client satisfaction with their coach, the intervention program, goal attainment, outcome, personal change, and levels of overall self-satisfaction.

Items on the COSS include questions related to satisfaction in terms the aspects mentioned above, for instance, “How satisfied are you with your coach?”, “How satisfied are you with the progress toward achieving your goals?”, “How satisfied are you with the personal change through coaching?”, and “How satisfied were you with yourself in the coaching?”

The purpose of these questions is to give you, the coach, an insight to your own strengths and weaknesses from the perspective of the client. Items on the COSS are rated on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (very satisfied).

As previously discussed, the coach-client relationship is paramount to coaching outcomes. The Working Alliance Inventory (WAI: Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) can be used to assess the strength of the coach-coachee relationship.

The 36-item instrument is widely used to assess the strength and quality of the relationship between the coach and client across three subscales: Task, Goal, and Bond. A 12-item short-form version of the WAI was later developed by Tracey & Kokotovic (1989).

Validation studies have shown that the WAI and WAI short-form present good construct validity and high reliability (Corbière, Bisson, Lauzon, & Ricard, 2006).

Becoming aware of the ways in which you can improve as a coach allows you to reassess the areas that require more attention. Any areas highlighted through client feedback can be addressed and developed further so you can continue on your journey as a skilled coach.

More Relevant Resources (on our blog)

To support coaches, we have a great various resources in our blog that you can access. We list them below.

Goal-Setting

The importance of goal setting within the coaching process is vital to achieving positive results. You can discover more about the psychology and research behind the goal-setting process in this article, and a collection of 47 goal-setting exercises, tools, and games.

Additionally, if you would like to know more about the key principles and techniques behind the goal-setting process, and advice on how best to achieve those goals, check out the goal-setting article on the Positive Psychology blog.

This information-packed article contains some excellent guidance on determining and setting life goals, how to prioritize goals, and techniques for achieving the success that you can incorporate into your coaching programs to use with clients.

You can also access 87 tried and tested goal setting exercises to help you guide clients in setting realistic and achievable goals.

Strengths

This article on leadership and strengths describes the importance of utilizing strengths in the workplace and how leaders can best apply a strength-based approach to their team or employees.

You will find a selection of 7 strengths-finding tests and questionnaires, additionally, why not check out these TED Talks about VIA character strengths and virtues.

Appreciative Inquiry

You can find a comprehensive list of recommended appreciative inquiry books that provide an overview of the key concepts and how best to apply appreciative inquiry to a variety of contexts.

If you are interested in learning more about how best to apply appreciative inquiry to the coaching process, you will find a comprehensive selection of relevant tools, exercises, and activities here.

Emotional Intelligence

If emotional intelligence is a concept you would like to learn more about or introduce to your coaching process, you can find further information on the importance of emotional intelligence and EI training on the Positive Psychology blog.

Additionally, you can check out these articles which give access to EI tests, activities, exercises, and recommended reading.

Self-Acceptance

The Science of Self-Acceptance© is a science-based online class designed to help you support clients as they learn to successfully build a healthy relationship with themselves.

This self-paced masterclass provides you with the materials required to deliver high-quality coaching and effectively guide clients in creating a more accepting and satisfying relationship with themselves.

Other Resources

Here you will find eight indispensable positive psychology coaching skills that will make you a valuable, sought-after practitioner.

17 Positive Psychology Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

A Take-Home Message

Being a great coach is an art form; not everyone can do it with ease. To many, it may seem like an effortless skill, but in reality, the very best coaches inspire, empower, and motivate their clients to progress and succeed.

While a dictionary will offer a blunt yet technically accurate definition, when discussing coaching through the lens of positive psychology we’re focusing on the practices therein, maximal efficiency coaching strategies and crucially, the subjective benefits and well-being promoted by coaching interventions.

I hope you have found this article to be a useful source of ideas, exercises, and assessment tools that can be incorporated into a variety of coaching contexts to help tailor your programs to meet the needs of your clients.

Let us know in the comments if you’ve tried out any of the activities detailed above, have they helped you to help others?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Cheema, A., & Bagchi, R. (2011). The Effect of Goal Visualization on Goal Pursuit: Implications for Consumers and Managers. Journal of Marketing, 75, 109–123.

- Colton, A. B., & Sparks-Langer, G. M. (1993). A conceptual framework to guide the development of teacher reflection and decision making. Journal of Teacher Education, 44, 45-55.

- Cooper H. (2009). Using 260-degree feedback improves self-awareness. Coaching at Work, 3, 10.

- Cooperrider, D. L. (1986) Appreciative Inquiry: Toward a Methodology for Understanding and Enhancing Organizational Innovation. Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio.

- Corbière, M., Bisson, J., Lauzon, S., & Ricard, N. (2006). Factorial validation of a French short-form of the Working Alliance Inventory. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 15, 36–45.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Csikszentmihalyi, I.S. (2006). A Life Worth Living: Contributions to Positive Psychology. OUP: New York.

- de Haan, E., Grant, A. M., Burger, Y., & Eriksson, P.O. (2016). A large-scale study of executive and workplace coaching: The relative contributions of relationship, personality match, and self-efficacy. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68, 189-207

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75.

- Edmunds, A.L. (1998) Content, concurrent and construct validity of the leadership skills inventory. Roeper Review, 20, 281-284

- Ellinger, A. D., & Bostrom, R. P. (1999). Managerial coaching behaviors in learning organizations. Journal of Management Development, 18, 752–771

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: Experimental studies of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377–389.

- Fazel, P. (2013). Learning theories within coaching practice. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 80, 584-590.

- Fleenor, J.W. (1997). The relationship between the MBTI and measures of personality and performance in management groups. In C. Fitzgerald & L. Kirby (Eds.), Developing leaders: Research and applications in psychological type and leadership development (pp. 115-138). Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black.

- Folkman, J.R. (2006). The power of feedback: 35 principles for turning feedback from others into personal and professional change. Hoboken NY: John Wiley,

- Grant, A. M. (2014). Autonomy support, relationship satisfaction and goal focus in the coach–coachee relationship: Which best predicts coaching success? Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 7, 18–38.

- Gregory, J. B., Beck, J. W., & Carr, A. E. (2011). Goals, feedback, and self-regulation: Control theory as a natural framework for executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 63, 26-38.

- Hiemstra, R. (2001). Uses and benefits of journal writing. In L. M. English & M. A. Gillen, (Eds.), Promoting journal writing in adult education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Herman-Stahl, M.A., Stemmler, M., & Peterson A. (1994).Approach and avoidant coping: implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 24, 649-665.

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 223-233.

- Ianiro, P., Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., & Kauffeld, S. (2014). Coaches and Clients in Action: A Sequential Analysis of Interpersonal Coach and Client Behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30.

- Karnes, F. A. & Chauvin, J. C. 1985. Leadership Skills Inventory: Administration Manual and Manual of Leadership Activities, East Aurora, NY: D.O.K. Pub.

- Kauffman, C. (2006). Positive Psychology: The Science at the Heart of Coaching. In D. R. Stober & A. M. Grant (Eds.), Evidence based coaching handbook: Putting best practices to work for your clients (pp. 219-253). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review: A meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 254 –284.

- Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Zak, P.J., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr , E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435 , 673 –676.

- Leonard-Cross, E. (2010). Developmental coaching: An evaluative study to explore the impact of coaching in the workplace. International Coaching Psychology Review, 5, 36–47.

- Locke, E.A. & Latham, G.P. (1991). A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance. The Academy of Management Review, 16.

- MacKay, G. & Lundie, J. (1998). GAS Released Again: proposals for the development of goal attainment scaling. International Journal of Disability. Development and Education. 217-231.

- Miller, W. & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Myers, Isabel Briggs. (1962). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator: Manual. Palo Alto, CA, US: Consulting Psychologists Press

- Palmer, A.M., Burns, S., & Bulman, C. (1994). Reflective practice in nursing. The growth of the professional practitioner. London: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

- Passmore, J., Rawle-Cope, M., Gibbes, C., & Holloway, M. (2006). MBTI types and executive coaching. The Coaching Psychologist, 2, 6-16.

- Pavot, W. G., Diener, E., Colvin, C. R., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Further validation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale: Evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57, 149-161.

- Pillans, G. (2014) ‘CRF Coaching Report’. London: Corporate Research Council.

- Sauer-Zavala, S.E., Walsh, E.C., Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A. & Lykins, E.L.B. (2013). Comparing mindfulness-based intervention strategies: differential effects of sitting meditation, body scan, and mindful yoga. Mindfulness, 4: 383.

- Schmidt, T. (2003) Coaching: An empirical study of success factors in individual coaching. Berlin.

- Seligman, M.E.P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

- Seligman, M.E.P. (2007). Coaching and positive psychology. Australian Psychologist, 42, 266 – 267.

- Schmidt, F., & Thamm, A. (2008). Wirkungen und Wirkfaktoren im Coaching. – Verringe-rung von Prokrastination und Optimierung des Lernverhaltens bei Studierenden. Work and Organizational Psychology Unit, University of Osnabrück, Germany.

- Suess, E. & Clark, J. (2014). Appreciative coaching for a new college leader. AI Practitioner, 16, 43-46.

- Tracey, T. J. and Kokotovic, A. M.1989. Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 1, 207–210.

- Wales, S. (2003). Why coaching? Journal of Change Management, 3, 275-282.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (56)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (39)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (44)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (13)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (42)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (22)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)

What our readers think

Great information for new coaches like me

I found this information to be affirming and insightful. You also provide additional coaching resources that will serve me well in providing services to my clients.

A cracking resource !! Well done all.

Hello Elaine,

This is great information about leadership and coaching. It has several examples, links and a granular view about the approach that takes place when committing to a coaching philosophy. Our organization is trying to make this shift from my prior experience and sharing best strategies to achieve more rewarding results from our team. This will be great to review and help guide us through the process.

Elaine – huge thanks to you. The article provided numerous great ideas and resources. I will be able to incorporate some in my Organization Development and Coaching practice. Thanks for generously sharing! Wishing you continued health and joy in your work.

Thank you for this article, Elaine – I plan to share the link to this article with the coaches I serve. Very thorough and practical.

You have just helped me launch a brand new career. very many thanks!

HR Consultant turned Life Coach.

Thank you very much for this article is very inspiring and powerful

Hello Elaine,

I am coming to the end of my initial health and wellness coach training course. Currently completing an assignment on positive mental heath and psychological well-being. I enjoy the learning material resources available on positive psychology.com and this article on coaching tools is most informative, concise, thought provoking and helpful. Thank you for sharing!

Emmet, in Ireland