Abraham Maslow, His Theory & Contribution to Psychology

Abraham Maslow was one of the most influential psychologists of the twentieth century.

Abraham Maslow was one of the most influential psychologists of the twentieth century.

Among his many contributions to psychology were his advancements to the field of humanistic psychology and his development of the hierarchy of needs.

Maslow’s career in psychology greatly predated the modern positive psychology movement, yet the field as we know it would likely look very different were it not for him.

This article will discuss some of Maslow’s formative experiences, his contributions to psychology, and his work’s relationship to the positive psychology movement.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology,Assertive At Work: 5 Tips to Increase Your Assertiveness including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

Abraham Maslow’s Life

Abraham Maslow was born in New York in 1908. He was the son of poor Russian-Jewish parents, who, like many others at the time, immigrated from Eastern Europe to flee persecution and secure a better future for their family (Hoffman, 2008).

Throughout various interviews, Maslow described himself as neurotic, shy, lonely, and self-reflective throughout his teens and twenties. This was, in part, because of the racism and ethnic prejudice he experienced owing to his Jewish appearance. He himself, however, was non-religious.

Maslow also did not enjoy being in the family home, so he spent much of his time at the library, where he developed his academic gifts (DeCarvalho, 1991). Consequently, Maslow later attributed his interest in self-actualization and the optimization of the human experience to his timid nature and the isolation it caused (Frick, 2000).

Education and Career

After attending public school in a working-class neighborhood in New York, Maslow attended the University of Wisconsin to study psychology. Initially, he was interested in philosophy, but he soon grew frustrated with its inapplicability to real-world situations and switched his focus to psychology (Frick, 2000).

Maslow was originally engaged in the field of behaviorism, which argues that human behavior can be explained and altered using forms of conditioning. In line with the laboratory-based methods at the time, Maslow conducted research with dogs and apes, and some of his earliest works looked at the emotion of disgust in dogs and the learning processes of primates (DeCarvalho, 1991).

While Maslow ultimately pivoted from behaviorism, he was observed to have remained staunchly loyal to the principles of positivism throughout all stages of his education and career, which are at the foundation of this branch of psychology (Hoffman, 2008).

According to this philosophy, only that which is scientifically verifiable or can be shown using logical or mathematical proof is considered valid.

As such, Maslow was a firm believer in the power of empirical data and measurability for forwarding human knowledge. He was known to have resisted the interest in mysticism that dominated in the 1960s, preferring instead to study businesses and entrepreneurship (Hoffman, 2008).

Maslow eventually studied gestalt psychology at the New School for Social Research in New York. He later joined the faculty of Brooklyn College and rose to become head of the psychology department at Brandeis University in Waltham, where he remained until 1969 (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2021).

During his career, Maslow co-founded the Journal of Humanistic Psychology in 1961, and the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology in 1969 (Richards, 2017). Today, both journals are highly cited, well-respected outlets in their fields, serving as a tribute to Maslow’s legacy in the field of psychology.

The Impact of World War II

With the onset of World War II, Maslow’s intellectual focus is reported to have changed, and this was when his work began to shift the landscape of the psychology field. At the time, Maslow was thirty-three years old and the father of two children.

In his writings, he lamented that the U.S. forces did not understand the German opposition and felt that the field of psychology could help facilitate understanding and restore peace to the world (Hoffman, 1999).

Therefore, given the horrors of the war, Maslow conducted his research with a renewed sense of urgency. This led to his famous works on the concept of self-actualization and the introduction of his seminal hierarchy of needs in the mid-1940s (Hoffman, 2008).

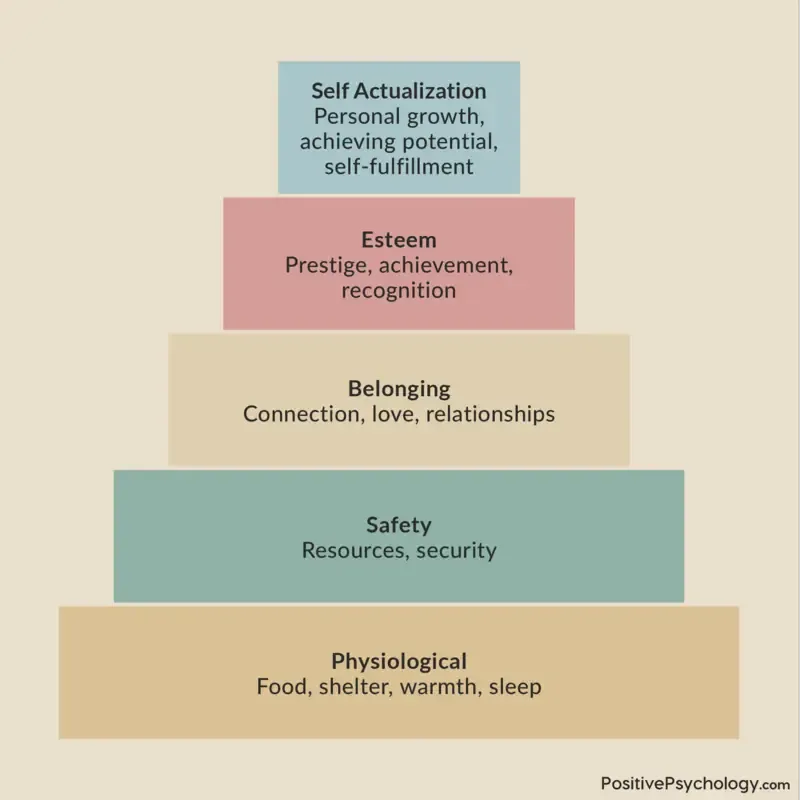

According to Maslow’s popular Hierarchy of Needs model, all human beings have needs relating to five key domains:

- Physiological

- Safety

- Love/belonging

- Esteem

- Self-actualization.

Maslow initially argued that these needs have a hierarchical order, depicting that needs at the most basic levels require fulfillment before a higher level can be fulfilled, as visualized in the pyramid.

In line with this hierarchy, our most basic needs relate to physiology (i.e., nutrition, warmth, and rest), and the most transcendent needs relate to self-actualization (i.e., achieving one’s full potential and self-fulfillment). Over the years, Maslow (1970) made some important revisions to his initial theory, admitting that:

- The hierarchy’s order is not as rigid as he initially proposed; instead, it is flexible based on external circumstances and individual differences.

- Most human behavior is multi-motivated, meaning that any behavior simultaneously aims to fulfill many needs.

- Three more levels could be added: cognitive needs, aesthetic needs, and transcendence needs (e.g., mystical, aesthetic, sexual experiences, etc.).

Cross-cultural research by Tay and Diener (2011) supports the view that there are universal human needs regardless of cultural differences, but the order of importance is influenced by culture.

Additionally, this research has shown that needs work independently, meaning that even if one’s basic needs are not fulfilled, one can still benefit from fulfilling needs at other levels. So, even if we are cold, we can still be happy with our friends.

Research and practice within positive psychology aim to support individuals in fulfilling their needs at all levels by capitalizing on their strengths, values, and intrinsic motivation, ultimately enhancing wellbeing (Proyer et al., 2015).

Maslow’s Contributions to Humanistic Psychology

Soon after Maslow began his career, he grew frustrated with the two dominant forces of psychology at the time, Freudian psychoanalysis and behavioral psychology (Koznjak, 2017).

Maslow believed that psychoanalysis focused too much on “the sick half of psychology” (Koznjak, 2017, p. 261). Likewise, he believed that behaviorism did not focus enough on how humans differ from the animals studied in behaviorism. He thus contributed to the third force of psychology that arose in response to this frustration: humanistic psychology.

Humanistic psychology gained influence in the mid-20th century for its focus on individuals’ innate drive to self-actualize, express oneself, and achieve their full potential.

Such foci represented a significant shift from the pathologizing and behaviorist approaches of the past, and Abraham Maslow’s work is widely considered having been at the center of this movement.

At the core of the humanistic psychology movement was the idea from gestalt psychology that human beings are more than just the sum of their parts and that spiritual aspiration is a fundamental part of one’s psyche.

Maslow himself was known to have been a big believer in this view; he was widely known for his optimism throughout his research. Further, his works were some of the first to deviate from psychology’s dominant focus on pathology and instead explore what it takes for humans to reach their full potential.

A key reason why Maslow’s work triggered a movement is owed to the way he positioned the role of human unconsciousness. Like Freud, a proponent of the dominant psychoanalytic approach at the time, Maslow acknowledged the presence of the human unconscious (Maslow, 1970).

However, whereas Freud argued that much of who we are as people is inaccessible to us, Maslow argued people are acutely aware of their own motivations and drives in an ongoing pursuit of self-understanding and self-acceptance. These ideas were ultimately reflected in his seminal works on self-actualization and his hierarchy of human needs (Maslow, 1970).

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

In 1943, Maslow published the epoch-making article of his career, A Theory of Human Motivation, which appeared in the journal, Motivation and Personality (DeCarvalho, 1991). In the paper, Maslow argued that “the fundamental desires of human beings are similar despite the multitude of conscious desires” (Zalenski & Raspa, 2006, p. 1121).

According to the theory, humans possess higher- and lower-order needs, which are arranged in a hierarchy.

These needs are:

- Physiological needs;

- Safety;

- Belongingness and love;

- Esteem; and

- Self-actualization (Maslow, 1943).

In his article, Maslow (1943) describes these needs as being arranged in a hierarchy of prepotency.

In other words, the first level of needs are the most important and will monopolize consciousness until they are addressed. Once one level of needs is taken care of, the mind moves on to the next level, and so on, until self-actualization is reached.

Levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy

Let’s inspect each of the levels in Maslow’s hierarchy.

At the bottom of the hierarchy are physiological needs, which are considered universal. Among the physiological needs are air, water, food, sleep, health, clothes, and shelter. These needs’ positioned at the bottom of the pyramid signifies they are fundamental to human wellbeing and will always take priority over other needs.

Next in the hierarchy are safety needs. If a person does not feel safe in their environment, they are unlikely to guide attention toward trying to meet higher-order needs. In particular, safety needs include personal and emotional security (e.g., safety from abuse), financial security, and wellbeing.

Third in the hierarchy is the need for love and belonging through family connections, friendship, and intimacy.

Humans are wired for connection, meaning that we seek acceptance and support from others, either one-on-one or in groups, such as clubs, professional organizations, or online communities. In the absence of these connections, we fall susceptible to states of ill-being, such as clinical depression (Teo, 2013).

The fourth level of the hierarchy is esteem needs. According to Maslow, there are two subtypes of esteem. The first is esteem reflected in others’ perceptions of us. That is, esteem in the form of prestige, status, recognition, attention, appreciation, or admiration (Maslow, 1943).

The second form of esteem is rooted in a desire for confidence, strength, independence, and the ability to achieve. Further, Maslow notes that when our esteem needs are thwarted, feelings of inferiority, weakness, or helplessness are likely to arise (Maslow, 1943).

Self-Actualization, Peak Experiences and Self-Transcendence Needs

At the top of Maslow’s hierarchy is self-actualization. According to Maslow, humans will only seek the satisfaction of this need following the satisfaction of all the lower-order needs (Maslow, 1943).

While scholars have refined the definition of self-actualization over the years, Maslow related it to the feeling of discontent and restlessness when one is not putting their strengths to full use:

“A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately happy. What a man can be, he must be. This need we may call self-actualization.”

Maslow (1943, p. 382)

Examples of self-actualization needs include the acquisition of a romantic partner, parenting, the utilization and development of one’s talents and abilities, and goal pursuit (Deckers, 2018).

Toward the end of his career, Maslow revisited his original conceptualization of the pyramid and argued a sixth need above self-actualization. He called this need self-transcendence, defined as a person’s desire to “further a cause beyond the self and to experience a communion beyond the boundaries of the self through peak experience” (Koltko-Rivera, 2006, p. 303).

Examples of behaviors that reflect the pursuit of self-transcendence include devoting oneself to discovering a ‘truth,’ supporting a cause, such as social justice or environmentalism, or seeking unity with what is perceived to be transcendent or divine (e.g., strengthening one’s relationship with God).

According to Maslow, those pursuing self-actualization and self-transcendence are more likely to have peak experiences, which are profound moments of love, rapture, understanding, or joy (Maslow, 1961).

Examples of peak experiences can include mystical experiences, interactions with nature, and sexual experiences wherein a person’s sense of self transcends beyond the personal self (Koltko-Rivera, 2006).

Criticisms and Modern Applications of Maslow’s Hierarchy

While modern research has confirmed the presence of universal human needs (Tay & Diener, 2011), most psychologists would agree that there is insufficient evidence to suggest such needs exist within a hierarchy.

This is one of just several criticisms of Maslow’s hierarchy and work. Other issues raised by scholars are:

- The failure to account for cultural differences stemming from one’s upbringing within an individualist versus a collective society, as these differences may influence how a person prioritizes their needs (Wahba & Bridwell, 1976);

- The positioning of sex within the hierarchy which Maslow argued falls under physiological needs (Kenrick, Griskevicius, Neuberg, & Schaller, 2010); and

- The possibility that the ordering of needs may change depending on region, geopolitics, and so forth. For instance, the positioning of safety and physiological needs in the hierarchy may change during times of war (Tang & West, 1997).

Despite these criticisms, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is still widely taught and a staple of any introductory psychology course. Further, the hierarchy has been adapted for use across a range of fields, including urban planning, development, management, and policing (de Guzman & Kim, 2017; Scheller, 2016; Zalenski & Raspa, 2006).

Among these modern applications of the theory are works adapting the theory to apply to communities rather than to individuals (de Guzman & Kim, 2017; Scheller, 2016), suggesting that Maslow’s hierarchy has influenced modern psychology in ways he likely did not intend.

Why Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Matters – The School of Life

Abraham Maslow and Positive Psychology

So what does Abraham Maslow have to do with positive psychology?

According to humanistic psychologist Nelson Goud, “the recent Positive Psychology movement focuses on themes addressed by Maslow over 50 years ago.” Goud also believed “that Maslow would encourage the scholarly approach [positive psychology] uses for studying topics such as happiness, flow, courage, hope and optimism, responsibility, and civility” (Goud, 2008, p. 450).

More than anything, both Maslow and proponents of positive psychology are driven by the idea that traditional psychology has abandoned studying the entire human experience in favor of focusing on mental illness (Rathunde, 2001).

Indeed, Maslow held a conviction that none of the available psychological theories and approaches to studying the human mind did justice to the healthy human being’s functioning, modes of living, or goals (Buhler, 1971).

To proponents of positive psychology, this reasoning should sound familiar. In fact, Maslow even used the term “positive psychology” to refer to his brand of humanistic psychology, though modern positive psychologists like Martin Seligman claim that humanistic psychology lacks adequate empirical validation (Rennie, 2008).

At the end of the day, both proponents of positive psychology and Maslow believe(d) that humanity is more than the sum of its parts and especially more than its illnesses or deficiencies. To a positive psychologist, optimizing the life and wellbeing of a healthy person is just as important as normalizing the life of a person who is sick, and Abraham Maslow helped legitimize this idea within the field of psychology.

A Take-Home Message

If we are to sum up Maslow’s impact on the field of psychology, we might credit him for encouraging a generation of psychologists to think more holistically about their approach to studying the human condition.

For the psychologists of the time, pathologizing and theories from behaviorist research with animals were some of the only tools available to understand people’s complex inner worlds. Yet, these tools were inadequate as they failed to account for the uniqueness of each individual.

Shaped by his experiences as a child and during WWII, Maslow introduced a whole new set of tools to the psychologist’s toolkit, enabling scientists and practitioners to affect people’s lives positively beyond mental illness and treating symptoms.

It is clear that Maslow was driven by a desire to help people live the best lives they could, acknowledging their unique humanity along the way. May his work and dedication to pursuing human happiness serve as an inspiration to us all.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Buhler, C. (1971). Basic theoretical concepts of humanistic psychology. American Psychologist, 26(4), 378-386.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

- DeCarvalho, R. J. (1991). Abraham H. Maslow (1908-1970): An intellectual biography. Thought: Fordham University Quarterly, 66(1), 32-50.

- Deckers, L. (2018). Motivation: Biological, psychological, and environmental (5th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- de Guzman, M. C., & Kim, M. (2017). Community hierarchy of needs and policing models: toward a new theory of police organizational behavior. Police Practice and Research, 18(4), 352-365.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2021). Abraham Maslow. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abraham-H-Maslow

- Frick, W. B. (2000). Remembering Maslow: Reflections on a 1968 interview. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 40(2), 128-147.

- Goud, N. (2008). Abraham Maslow: A personal statement. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(4), 448-451.

- Hoffman, E. (1999). The right to be human: a biography of Abraham Maslow (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Hoffman, E. (2008). Abraham Maslow: A biographer’s reflections. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(4), 439-443.

- Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 292-314.

- Koltko-Rivera, M. E. (2006). Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology, 10(4), 302-317.

- Koznjak, B. (2017). Kuhn meets Maslow: The psychology behind scientific revolutions. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 48(2), 257-287.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(1), 370-396.

- Maslow, A. H. (1961). Peak experiences as acute identity experiences. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 21(2), 254-262.

- Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and Personality.

- Proyer, R. T., Wellenzohn, S., Gander, F., & Ruch, W. (2015). Toward a better understanding of what makes positive psychology interventions work: Predicting happiness and depression from the person intervention fit in a follow-up after 3.5 years. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7(1), 108-128.

- Rathunde, K. (2001). Toward a psychology of optimal human functioning: What positive psychology can learn from the “experiential turns” of James, Dewey, and Maslow. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 41(1), 135-153.

- Rennie, D. L. (2008). Two thoughts on Abraham Maslow. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(4), 445-448.

- Richards, W. A. (2017). Abraham Maslow’s Interest in psychedelic research: A Tribute. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(4), 319-322.

- Scheller, D. S. (2016). Neighborhood hierarchy of needs. Journal of Urban Affairs, 38(3), 429-449.

- Tang, T. L. P., & West, W. B. (1997). The importance of human needs during peacetime, retrospective peacetime, and the Persian Gulf War. International Journal of Stress Management, 4(1), 47-62.

- Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354-365.

- Teo, A. R. (2013). Social isolation associated with depression: A case report of hikikomori. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(4), 339-341.

- Wahba, M. A., & Bridwell, L. G. (1976). Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15(2), 212-240.

- Zalenski, R. J., & Raspa, R. (2006). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: A framework for achieving human potential in hospice. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9(5), 1120-1127.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (42)

- Coaching & Application (56)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (17)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (39)

- Meaning & Values (25)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (43)

- Optimism & Mindset (32)

- Positive CBT (25)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (44)

- Positive Emotions (30)

- Positive Leadership (13)

- Positive Psychology (32)

- Positive Workplace (33)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (42)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (36)

- Software & Apps (22)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (44)

- Therapy Exercises (35)

- Types of Therapy (58)

What our readers think

You precisely explained and your work flows very well. Thank you so much for adding insight into Humanistic psychology. Remain blessed and sharing articles